Part Of: Sociality sequence

Followup To: Intro to Confabulation

Content Summary: 2000 words, 20 min read

We do not have direct access to our mental lives. Rather, self-perception is performed by other-directed faculties (i.e., mindreading) being “turned inwards”. We guess our intentions, in exactly the same way we guess at the intentions of others.

Self-Knowledge vs Other-Knowledge

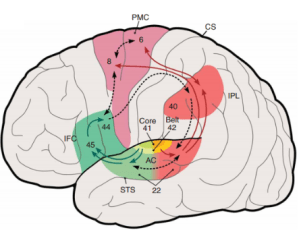

The brain is organized into perception-action cycles, with decisions mediating these streams. We can represent this thesis as a simple cartoon, which also captures the abstraction hierarchy (concrete vs abstract decisions) and the two loop hypothesis (world vs body).

Agent files are the mental records we maintain about our relationships with people. Mindreading denotes the coalition of processes that attempt to reverse engineer the mental state of other people: their goals, their idiosyncratic mental states, and even their personality. Folk psychology contrasts this interpretive method of understanding other people with our ability to understand ourselves.

We have powerful intuitions that self-understanding is fundamentally different than other-understanding. The Cartesian doctrine of introspection holds that our mental states and mechanisms are transparent; that is, directly accessible to us. It doesn’t matter which mental system generates the attitude, or why it does so – we can directly perceive all of this.

Our Unconscious Selves

Cartesian thinking has fallen out of favor. Why? Because we discovered that most mental activity happens outside of conscious awareness.

A simple example should illustrate. When we speak, the musculature in our vocal tracts contort in highly specific ways. Do you have any idea which muscles move, and in which direction, to speak? No – you are merely conscious of the high-level desire. The way that those instructions are cached out at the more detailed motor commands is opaque to you.

The first movement against transparency was Freud, who championed that a repression hypothesis: that unconscious beliefs are too depraved to be admitted to consciousness. But, after a brief detour through radical behaviorism, modern cognitive psychology tends to avow a plumbing hypothesis: that unconscious states are too complex (or not sufficiently useful) to merit admission to consciousness.

The distinction between unconscious and conscious processes can feel abstract, until you grapple with the limited capacity of consciousness. Why is it possible to read one, but not two books simultaneously? Why is it possible for most of us to remember a new phone number, but not the first twenty digits of pi, after the first 15 minutes of exposure?

The ISA Theory

The Interpretive Sensory-Access (ISA) theory holds that our conscious selves are completely ignorant of our own mental lives save for the mindreading faculty. That is, the very same faculty used in our social interactions also constructs models of ourselves.

It is important to realize that the range of perceptual data available for self-interpretation is larger than that available for people outside of ourselves. For both types of mindreading, we have perceptual data on various behaviors. In the case of self-mindreading, we also have access to our subvocalizations (inner speech) and the low-capacity contents of the global broadcast, more generally.

Perhaps our mindreading faculties are more accurate, given they have more data on which to construct a self-narrative.

The ISA theory explains the behavior-identity bootstrap; i.e., why the “fake it until you make it” proverb is apt. By acting in accordance with a novel role (e.g., helping the homeless more often), we gradually begin to become that person (e.g., resonating to the needs of others more powerfully in general).

Theses, Predictions, Evidence

The ISA theory can be distilled into four theses:

- There is a single mental faculty underlying our attributions if propositional attitudes, whether to ourselves or to others

- That faculty has only sensory access to its domain

- Its access to our attitudes is interpretive rather than transparent

- The mental faculty in question evolved to sustain and facilitate other-directed forms of social cognition.

The ISA theory is testable. It generates the following predictions:

- No non-sensory awareness of our inner lives

- There should be no substantive differences in the development of a child’s capacities for first-person and third-person understanding.

- There should be no dissociation between a person’s ability to attribute mental states to themselves and to others.

- Humans should lack any form of deep and sophisticated metacognitive competence.

- People should confabulate promiscuously.

- Any non-human animal capable of mindreading should be capable of turning its mindreading abilities on itself.

These predictions are largely borne out in experimental data:

- Introspection-sampling studies suggest that some people believe themselves to experience non-sensory attitudes. These data is hard for ISA theory to accommodate. But it is also hard for introspection-based theories to reconcile with – if we had transparent access to our attitudes, why do some people only experience them with a sensory overlay?

- Wellman et al (2001) conducted a meta-analysis of well over 100 pairs of experiments in which children had been asked, both to ascribe a false belief to another persons and to attribute a previous false belief to themselves. They were able to find no significant difference in performance, even at the youngest ages tested.

- Other theorists (e.g., Nichols & Stich 2003) claim that autism exemplifies deficits in other-k but not in self-k, and schizophrenia is an impairment of self-k but not other-k. But on inspection, these claims have weak if nonexistent empirical support. These syndromes injure both forms of knowledge.

- Transparent self-knowledge should entail robust metacognitive competencies. But we do not. For example, the correlation between people’s judgments of learning and later recall are not very strong (Dunlosky & Metcalfe (2009)).

- The philosophical doctrine of first-person authority holds that we cannot hold false beliefs about our mental lives. The robust phenomena of confabulation discredits this hypothesis (Nisbett & Wilson (1977)). We are allergic to admitting “I don’t know why I did that”; rather, we invent stories about ourselves without realizing their contrived nature. I discuss this form of “sincere dishonesty” at length here.

- Primates are capable of desire mindreading, and their behavior is consistent with their possessing some rudimentary forms of self-knowledge.

The ISA theory thus receives ample empirical confirmation.

Competitors to ISA Theory

There are many competitors to the ISA account. For the below, we will use attitude to denote non-perceptual mental representations such as desires, goals, reasons and decisions.

- Source tagging theories (e.g., Rey 2013) hold that, whenever the brain generates a new attitude, the generating system(s) add a tag indicating their source. Whenever that representation is globally broadcast, our conscious selves can inspect the tag to view its origin.

- Attitudinal working memory theories (e.g., Fodor 1983, Evans 1982) hold that, in addition to a perception-based working memory system, there is a separate faculty to broadcast conscious attitudes and decisions.

- Constitutive authority theories (e.g., Wilson 2002, Wegner 2002, Frankish 2009) admit that conscious events (e.g., suppose we say I want to go to the store) do not directly cause action. However, we do attribute these utterances to ourselves, and the subconscious metanorm I DESIRE TO REALIZE MY COMMITMENTS works to translate these conscious self-attributions to unconscious action programs.

- Inner sense theories hold that, as animal brains increased in complexity, there was increasing need for cognitive monitoring and control. To perform that adaptive function, the faculty of inner sense evolved to generate metarepresentations: representations of object-level computational state. There are three important flavors of this theory:

But there are data speaking against these theories

- Contra source tagging, the source monitoring literature shows that people simply don’t have transparent access to the sources of their memory images. For example, Henkel et al (2000) required subjects to either see, hear, imagine as seen, or imagine as heard, a number of familiar events, such as a basketball bouncing. But people frequently misremembered which of these four mediums had produced their memory, when asked later.

- The capacity limits of sensory-based working memory explains nearly the entire phenomena of fluid g, also known as IQ (Colom et al 2004). If attitudinal working memory evolved alongside this system, it is hard to explain why it doesn’t contribute to fluid intelligence scores.

More tellingly, however, each of the above theories fails to explain confabulation data. Most inner sense theories today (e.g., Goldman 2006) adopt a dual-method stance: when confabulating, people are using mindreading; else people are using transparent inner sense. But as an auxiliary hypothesis, dual-method theories fail to explain the patterning of when a person will make correct versus incorrect self-attributions.

Biased ISA Theory

The ISA theory holds self-knowledge to be grounded in sparse but unbiased perceptual knowledge. But this does not seem to be the whole story. For we know that we are prone to overestimate the good qualities of the Self and Us, but underestimate the bad qualities of the Other and Them.

For example, the fundamental attribution error describes the tendency to explain our own failings as contingent on the situation, but the failings of others to immutable character flaws. More generally, the argumentative theory of reasoning posits a justification faculty which subconsciously makes our reasons rosier, and our folk sociology faculty demonizes members of the outgroup.

In social psychology, there is a distinction between dispositional beliefs (avowals that are generated live) and standing beliefs (those actively represented in long-term memory). The relationship between the content of what one says and the content of the underlying attitude may be quite complex. It is unclear whether these parochial biases act upon standing or dispositional beliefs.

Explaining Transparency

The following section is borrowed from Carruthers (2020).

In general, our judgments of others’ opinions come in two phases:

- First pass representation of the attitude expressed, relying on syntax, prosody, and the salient feature of conversational context.

- Lie Detection. Whenever the degree of support for the initial interpretation is lower than normal, or there is a competing interpretation in play that has at least some degree of support, or the potential costs of a misunderstanding are higher than normal, a signal would be sent to executive systems to slow down and issue inquiries more widely before a conclusion is reached.

Why do our self-attributions feel transparent? Plausibly, because, the attribution of self-attitudes only undergo the first stage (not subject to disambiguation and lie detection systems). This architecture would likely generate the following inference rules:

- One believes one is in mental state M → one is in mental state M.

- One believes one isn’t in mental state M → one isn’t in mental state M.

The first will issue in intuitions of infallible knowledge, and the second in the intuition that mental states are always self-presenting to their possessors.

For example, consider the following two sentences

- John thinks he has just decided to go to the party, but really he hasn’t.

- John thinks he doesn’t intend to go to the party, but really he does.

These sentences are hard to parse, precisely because the mindreading inference rules render them strikingly counterintuitive.

These intuitions may be merely tacit initially, but will rapidly transition into explicit transparency beliefs in cultures that articulate them. Such beliefs might be expected to exert a deep “attractor effect” on cultural evolution, being sustained and transmitted both because of their apparent naturalness. And indeed, transparency doctrines have been found in traditions from Aristotle, to the Mayans, to pre-Buddhist China.

Until next time.

Inspiring Materials

These views are more completely articulated in Carruthers (2011). For a lecture on this topic, please see:

Works Cited

- Carruthers (2011). The Opacity of Mind

- Carruthers (2020). How mindreading might mislead cognitive science

- Colom et al (2004). Working memory is (almost) perfectly predicted by g

- Evans (1982). The Varieties of Reference.

- Henkel et al (2000). Cross-modal source monitoring confusions between perceived and imagined events.

- Fodor (1983). The Modularity of Mind.

- Goldman (2006). Simulating Minds.

- Frankish (2009). How we know our conscious minds.

- Nichols & Stitch (2003). Mindreading: An Integrated Account of Pretence, Self-Awareness, and Understanding Other Minds

- Nisbett & Wilson (1977). Telling more than we can know: verbal reports on mental processes.

- Rey (2013). We aren’t all self-blind: A defense of modest introspectionism.

- Wilson (2002). Strangers to ourselves

- Wegner (2002). The illusion of conscious will.

What exactly is the scope of “introspection”? For example, where do things like the sense of familiarity or credence fit into the list of self-knowledge?

LikeLike

The epistemic emotions are treated in Carruthers (2011), section 9.5 fwiw. Loosely, epistemic feelings such as anxiety (which increases with uncertainty), or recognition memory = feeling of knowing, are operate on the subconscious, nonconceptual level. While such emotions are globally broadcast (they directly and transparently self-present) they do not bind to perceptual objects. This “radical fungibility of affect” explains how, when we are made to feel anxious by object A, we can often be deceived in attributing its source to object B.

Speaking more generally, in my view, the kinds of self-knowledge treated here seem to represent the social-narrative-personality fabric with which we form explicit beliefs about ourselves. The entire existence of the Hot Loop (including e.g., the cortical homunculus, and the default mode network as seat of interoception & allostasis) implies that the brain represents the body in myriad subconscious ways. It’s just that Narrative Self doesn’t have direct access to the Embodied Self (or, more accurately, the En-Selfed Body-Concept).

See also Kahneman Experiencing vs Remembering Self TED Talk, and Metzinger’s Being No One. The rabbit hole goes deep 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person