Part Of: Culture sequence

See Also: Kinship explains the IC Dimension

Content Summary: 1800 words, 9 min read

The Economics of Kinship

Kinship systems are solutions to economic problems.

In foraging societies, resources are scarce and dispersed. Hunter-gatherers that exploit a diversity of unevenly distributed food resources may need to hedge their bets by having kin in different places in times of need (Yellen and Harpending, 1972). They employ this loose (extensive) kinship.

In food production societies, resources become abundant and concentrated. Competing over resources becomes much more profitable. Agropastoralists need to keep their kin close by, to reduce the dilution of inheritable family wealth (Borgerhoff Mulder et al., 2009), and may help with kin-based resource defense of such wealth, which is more important for many agropastoral societies as opposed to hunter-gatherer societies. They employ tight (intensive) kinship.

Empirically, we see a tight correlation between kinship tightness and dependence on foraging:

Residence and Descent

Residence patterns describe where a new couple lives after marriage. Many foragers practice bilocal residence, with newlyweds flexibly choosing a residence that fits their needs. In contrast, most agriculturalists practice unilocal residence: consistently moving into the residence of the wife’s kin (matrilocality) or the husband’s kin (patrilocality).

Descent ideology reflects cultural norms about inherited wealth. Patrilineal systems have inheritance wealth flowing through the father’s descent; matrilineal systems have it flowing through the mother. Western surname systems, for example, reflect patrilineal logic.

According to main sequence theory, descent ideology tends to follow changes in residence pattern. Many foraging societies manifest patrilocality but not patrilineality, but not vice versa. Patrilineal societies require a patrilocal precedent, and matrilineal societies require a matrilocal precedent. This has been empirically confirmed by cross-cultural analyses (Divale 1984; Ember & Ember 1971).

Here is an example of societies from patrilocal to matrilocal residence, and back again. Avunculocality is residence with the man’s mother’s brother – his closest senior male matrilineal relative. It is a compromise between the matrilineal principle and pressure to keep related males residing in one community.

Many hunter-gatherer societies may tend toward bilocality as a means of adapting to fluctuations in sex ratio in small local groups (Lee 1972), with bilateral descent serving as the companion ideology.

We will discuss the matrilineal puzzle some other time, and for now confine our attention to patrilineal clans, which comprise the majority of unilineal systems.

What caused the shift to patrilineal descent? This ideology is correlated with sedentism and community stability, which explains its prevalence for agriculturalists and not foragers (Murdock 1949). But these factors don’t explain its prevalence in pastoralists (Korotayev 2004). To explain that, a third driver of patrilineal descent has been discovered: high warfare frequency (Ember et al 1974). One of the strongest predictors of warfare frequency is the “threat of unpredictable natural disasters destroying food supplies”, and pastoralists are especially susceptible to this sort of disaster.

Ember et al (1974) wrote,

We suggest that if allies are needed for offense or defense, it would be most advantageous to have a group to call upon which has no conflicting loyalties. If there are unilineal descent groups, every person belongs to just one set (or hierarchy of sets) of persons. A unilineal descent principle thus provides unambiguously discrete groups of people for collective action in competitive situations. In bilateral societies, where kin groups are overlapping and nondiscrete, individuals may have conflicting loyalties with respect to which particular set of kinsmen they should join in competitive conditions. In short, the speed and effectiveness of collective response in a competitive situation should be greater in a unilineal society and therefore we should expect unilineal descent groups to be more likely to occur.

Unilineal descent groups are distinctive in their sense of corporate identity (Fuentes 1953). If a member of one lineage kills a member of another, it is not the individual who is responsible to pay blood money. The group as a whole does. Similarly, the entire group competes over property rights to various economic resources (e.g., watering holes). This sense of corporate identity is reinforced by use of classificatory kinship: describing everyone in one’s community as descending from one (perhaps fictional) eponymous ancestor. Clans use kinship terms as a kind of political ideology, a behavior which we retain in modern nation-states in the guise of nationalism (Rodseth & Wrangham 2004).

Exogamy and Consanguineous Marriage

Tight kinship societies typically practice arranged marriage, with the parents (particularly the father) making most of the decisions. Patrilocal clans practice female exogamy, with daughters leaving their clan to go live with their husbands clan.

Indeed, marriages among kin are much more common in agropastoralist societies (Walker & Bailey 2014). One of the most common forms of consanguineous marriage is cross-cousin marriage. In patrilineal systems, parallel cousins are members of one’s own clan, and forbidden via incest taboos. Cross cousins do not participate in the same patrilineal group, and hence often are deemed eligible for marriage.

As long as parents are not too related, a little bit of consanguinity goes a long way. The small cost of genetic disorders is offset by social benefits of marriage alliances, creating a “Goldilocks Zone” of optimal mates at intermediate levels of relatedness (e.g., second cousins).

Consanguineous marriage might seem foreign. But they are the predominant social pattern of the Neolithic.

Fraternal Interest Groups

Unilineal descent appears linked to external warfare to control abundant, concentrated resources. But some groups also feature fierce competition within the group. In situations of internal war, patrilocal residence becomes spatially contiguous (Otterbain 1968; Ember et al 1974). Societies with internal war organize themselves into lineages (Ember et al 1974), with explicit (rather than vague) genealogies demarcating specific factional boundaries.

All of this suggests that internal war selects for fraternal interest groups (FIGs): large kinship-bonded male coalitions capable of military action. These power groups often unite within a men’s house or other exclusively masculine setting (Murphy 1957). FIGs manifest strongly in societies that are patrilocal, patrilineal, lineage-based, contiguous-residence, with high levels of consanguineous marriage. FIGs are not just associated with internal war, but also within-society violence and also feuding (van Velzen & van Wetering 1960, Otterbain & Otterbain 1965).

Rituals often serve to surveil and marshal social consensus. But with fraternal interest groups, direct enforcement of contracts becomes possible. This may explain why non-FIG societies use menarche rituals to safeguard marriage contracts, but FIG-based societies eschew these rituals in favor of explicit brideprice contracts (Price & Price 1984).

While light polygyny appears a human universal, these societies are more likely to practice it more extensively, and the polygynous intensity strongly correlates with even higher rates of consanguineous marriage. FIG societies manifest marital aloofness, and sexual segregation may occupy an inverse relationship with male violence (Whiting & Whiting 1975).

The Epidemiology of Kinship

What causes kinship tightness? We have already discussed (abundant and concentrated) resources and (internal and external) warfare. Let’s turn to another possible driver: parasite load (Fincher & Thornhill 2012). To understand this, let’s revisit first principles.

The immune system is a necessary but insufficient protection against disease. The visceral immune system is energetically costly (a 13% increase in metabolic expenditure is required to increase human body temperature by 1 degree Celsius), and temporarily debilitating (the syndrome is known as sickness behavior). In addition to a reactive system, animals take preventative measures against disease: a behavioral immune system (Schaller & Park 2011).

Disgust evolved to promote pathogen avoidance, and thus contributes to the behavioral immune system. But unfamiliar people traveling from distant groups represent contagion risk, even if they aren’t manifesting signs of infection. Xenophobia is mediated disgust, and intensifies when disease concepts are primed.

Everyone has a behavioral immune system; but it becomes more virulent in places of high parasite load. Stable, local, and fractionalized networks have fewer links with the rest of the community. This insulation reduces the risk of an infection entering the collective, allowing the participants to live longer. But it also restricts the group’s exposure to new technologies (Fogli & Veldkamp 2021).

Kinship Systems Across History

The niche of Sapiens was hunting and gathering. Only 9000 years ago we switched to agriculture, and hence to tight kinship systems.

The less nutritious diets of farmers left them shorter, sicker, and more likely to die young. But farmers did reproduce more quickly than hunter-gatherers. Farming societies spread across the landscape like an epidemic, driving out foragers in their path. Early farming spread not because it was a better lifestyle, but because farming communities with particular institutions beat mobile hunter-gatherer populations in intergroup competition.

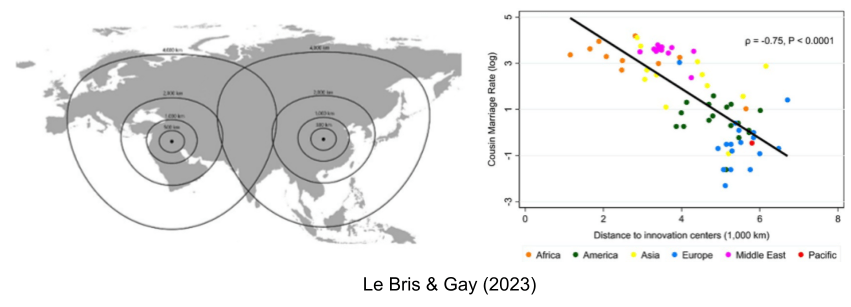

Kinship intensification events seems to emerge near agricultural centers (e.g., Uruk) and diffuse outwards at a remarkably slow pace. Kinship systems seem very stable.

Tight kinship won. The severe competition manifested by this system is visible in the Y-chromosome:

Tight kinship won. This is why all major world religions (with the exception of the Roman Catholic Church, for reasons we’ll explore next time) encourage or permit intensive kinship strategies including cousin marriage.

Tight kinship won, so we would expect the entire modern world to have it. Well, not exactly:

From 9,000 to 1,000 years ago, this map may indeed have been bright red. However, loose kinship has made a resurgence in Western (European or European-descended) societies. We’ll explore why this happened next time.

Implications

Most human societies are conceptualized as residing on a continuum between two kinship systems: tight and loose kinship.

The individualism-collectivism (IC) dimension of cultural variation is widely regarded as the most significant dimension of cultural variation. As we will see next time, kinship systems (and its drivers like parasite load) drive the IC dimension.

While foragers are patriarchal (due to our inheritance of primate polygyny), we will see patriarchy was much exacerbated by the tightening of kinship systems.

While polity ratcheting denotes an overall increase in group size since the Neolithic, economic growth was essentially non-existent until the Industrial Revolution. The reversion to loose kinship (i.e., individualism) may help explain the advent of growth.

References

- Bittles & Black (2010). Consanguineous marriage and human evolution.

- Borgerhoff et al (2009). The intergenerational transmission of wealth and the dynamics of inequality in pre-modern societies.

- Divale (1984). Matrilocal residence in pre-literate society.

- Ember & Ember (1971). The conditions favoring matrilocal versus patrilocal residence

- Ember et al (1974). On the development of unilineal descent

- Enke (2019). Kinship, Cooperation, and the Evolution of Moral Systems.

- Fincher & Thornhill (2012). Parasite-stress promotes in-group assortative sociality: the cases of strong family ties and heightened religiosity.

- Fogli & Veldkamp (2021). Germs, Social Networks, and Growth.

- Fuentes (1953). The structure of unilineal descent groups

- Helgason et al (2008). An Association Between the Kinship and Fertility of Human Couples

- Korotayev (2004). Unilocal Residence and Unilineal Descent: A Reconsideration

- Le Bris & Gay (2023). Distance to innovations, kinship intensity, and psychological traits

- Lee (1972). !Kung Spatial Organization: an ecological and historical perspective.

- Murdock (1949). Social Structure

- Murphy (1957). Intergroup hostility and social cohesion

- Rodseth & Wrangham (2004). Human Kinship: a continuation of politics by other means

- Schaller & Park (2011). . The Behavioral Immune System (and Why It Matters)

- Walker & Bailey (2014). Marrying kin in small-scale societies.

Kevin – Good morning. Thanks for this piece. I’ve explored most of these themes separately, but interestingly, never through the specific lens of kinship as a system per se.

Some quick notes:

best, Pat

LikeLike