Part Of: History sequence

Content Summary: 5000 words, 25 min read

The Indo-European Language Family

In 1786, a British judge and linguist in India was asked to learn Sanskrit, to better understand how to integrate British and Hindu law. Three years after his arrival in Calcutta, Sir William Jones wrote,

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure: more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either; yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.

Language variation is pervasive. We speak more like people we interact with, than people with whom we do not. Thus, the separation of speech communities causes language drift.

The discovery of language families, with their branching patterns, is a hallmark of comparative linguistics. These linguistic trees were a source of inspiration to Charles Darwin in his discovery of common descent and natural selection. The Indo-European language family is the largest known language tree, with some 3 billion speakers. The geographical breadth of this single language family suggests its original language community, the Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) were politically successful. When and where did the first speakers of PIE live?

Who Spoke PIE?

There are three theories:

- Some archaeologists are content to deny PIE was spoken by any particular peoples. They claim that Indo-European similarities derive from extensive borrowing. But linguists can differentiate creolizations from linguistic descent.

- Colin Renfrew (1987) advanced the Anatolian hypothesis, which attributes early Neolithic farmers as the original speakers of PIE. This explains why the earliest branch in the PIE family is located in modern-day Turkey.

- Maria Gimbutas (1965) advanced the steppe hypothesis, which has pastoralists from the Pontic-Caspian steppes as the original speakers of PIE.

Language evolution involves systematic changes in pronunciation. For example, English Great Vowel Shift makes Old English nearly impossible for modern speakers to understand. But if you can detect where and when these changes occur for a particular word, it is possible to reconstruct the word as it was spoken originally. These are called cognates.

A list of cognates sheds light on the original PIE vocabulary. This in turn can help us understand the people who spoke it. As Edward Sapir once said, “the complete vocabulary of a language may indeed be looked upon as a complex inventory of all the ideas, interests, and occupations that take up the attention of the community.”

The PIE vocabulary includes language for clans. Their gods were all male, suggesting a patrilineal society. They also had a word for chief. Patron-client institutions, a common thread in Indo-European cultures, are common among chiefdoms.

PIE includes words related to wool textiles, the wheel, and wagons. None of these existed before about 4000 BCE. This suggests that Proto-Indo-European was spoken after 4000-3500 BCE. It also doesn’t include many agriculturalist concepts, but an elaborate understanding of domesticated animals.

Finally, temperate-zone flora and fauna dominate in the reconstructed vocabulary; with no tropical or Mediterranean species. And PIE borrows many words from Proto-Uralic, and less clear linkages to Kartvelian language of the Caucasus region.

Taken together, these data suggest the original PIE language community were Yamnaya pastoralists in the Pontic-Caspian steppes in 4000 BCE. This group’s migration patterns are consistent with the branching structure of the language family. These people also exerted an enormous influence on geopolitics in the Bronze Age, which explains their linguistic success.

The Politics of Migration

The topic of migration is politically sensitive. Flannery & Marcus (2012) suggests that the “we were here first” principle is a cultural universal, ubiquitously invoked in land disputes. Absence of migration provides clear answers to this question. But evidence of genetic change can be deployed as ammunition in these matters.

Anthony (2012) notes the politicization of Indo-European research:

The problem of Indo-European origins was politicized almost from the beginning. It became enmeshed in nationalist and chauvinist causes, nurtured the murderous fantasy of Aryan racial superiority, and was actually pursued in archaeological excavations funded by the Nazi SS… In Russia some modern nationalist political groups and neo-Pagan movements claim a direct linkage between themselves, as Slavs, and the ancient “Aryans.” In the United States white supremacist groups refer to themselves as Aryans. There actually were Aryans in history – the composers of the Rig Veda and the Avesta – but they were Bronze Age tribal people who lived in Iran, Afghanistan, and the northern Indian subcontinent. It is highly doubtful that they were blonde or blue-eyed, and they had no connection with the competing racial fantasies of modern bigots.

This Nazi legacy caused the entire topic of migration to become taboo in post-WWII archaeology. The new orthodoxy insisted that changes in language and material culture is not sufficient evidence for migration. “Pots are not people” was their rallying cry.

But migration does happen. In the early 2000s, oxygen and strontium isotopes were showing that many Neolithic people died far from where they were born – they had migrated. Even very long-range migrations occurred:

The Afanasievo culture was intrusive in the Altai, and it introduced a suite of domesticated animals, metal types, pottery types, and funeral customs that were derived from the Volga-Ural steppes. This long-distance migration almost certainly separated the dialect group that later developed into the Indo-European languages of the Tocharian branch, spoken in Xinjiang in the caravan cities of the Silk Road around 500 CE but divided at that time into two or three quite different languages, all exhibiting archaic Indo-European traits. Most studies of Indo-European sequencing put the separation of Tocharian after that of Anatolian and before any other branch. The Afanasievo migration meets that expectation. The migrants might also have been responsible for introducing horseback riding to the pedestrian foragers of the northern Kazakh steppes, who were quickly transformed into the horse-riding, wild-horse-hunting Botai culture just when the Afanasievo migration began.

The Ancient DNA Revolution

Modern DNA does contain information about the past, of course. But the further back you look, the more tenuous the inferential bridge. Ancient DNA can directly verify historical hypotheses about genetic admixture, population replacement, and natural selection. All DNA is lost within a few million years, so this technique cannot inform anthropogenic events (other proteins might). But ancient DNA does illuminate the Pleistocene and Holocene – the entire history of Sapiens.

The scientific community, which had been using teeth, discovered that sampling of cochlea of the petrous bone could recover two orders of magnitude more DNA! And genome sequencing has become affordable. Just as radiometric dating brought about the second scientific revolution in archaeology, with ancient DNA (aDNA) we are in the midst of the third scientific revolution.

Paleogenetic information often necessitate revisions to hypotheses based on linguistics and material culture. In our case, Indo-European studies were revolutionized in 2015.

First, paleogenetic data showed that the agricultural revolution (~9kya) was a movement of people, not a movement of ideas. During the early Neolithic ancestry derives from both sources:

But less than 5,000 years ago, a new genetic signature started to predominate. The Yamnaya genome arrives and establishes a lion’s share of modern European ancestry (Allentoft et al 2015; Haak et al 2015). Massive migration from the steppe was the source for Indo-European languages in Europe.

Even David Anthony, a leading proponent of the steppe hypothesis, did not suggest genetic diffusion. He proposed that material and linguistic aspects of Yamnaya culture spread through imitation and proselytization. A genetic version of the steppe hypothesis is now consensus. Even the leading proponent of the Anatolian hypothesis Colin Renfrew has by now endorsed the steppe hypothesis.

Massive migrations are not confined to the Yamnaya. They are pervasive across continents, and across centuries. aDNA showed that inferences derived from modern DNA were more problematic than expected, because human mobility was surprisingly high (Pickrell & Reich 2014).

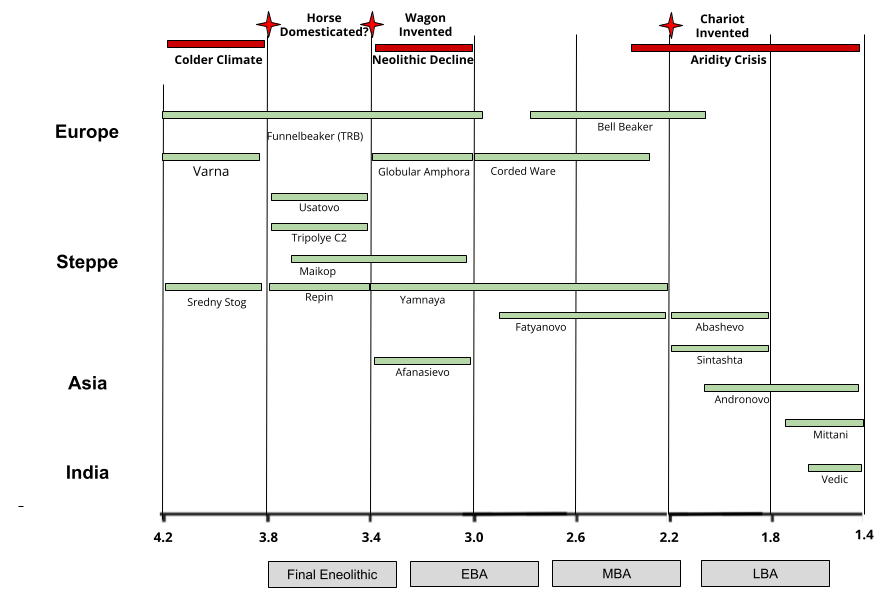

We will be diving into the details of the Yamnaya story, starting with their origins in the Eneolithic, their overwhelming Europe in the Early Bronze Age (EBA), and then the Indian subcontinent in the Late Bronze Age (LBA). We will close with a discussion on whether this migration was a genocide, or something else entirely.

The Kuban Steppe in the Eneolithic

In the Northern Caucasus Mountains, chiefs appeared among what had been small-scale farmers. The Maikop chiefs were very rich, and also left kurgan graves similar to those found in Suvorovo-Novodanilovka. This was a Mesopatamian outpost, with Uruk symbols of power adorning their graves.

Ancient DNA data reveals three clines in the Eneolithic steppe (Lazaridis & Reich 2024). The Volga Cline represents genetic admixture along the Volga river, and derives from Eastern Hunter Gatherers (EHG). The Dnipro Cline follows the Dnipro River, and derives from the Ukraine Neolithic Hunter Gatherer (UNHG) population. Finally, the Caucasus-Lower Volga (CLV) Cline is situated in the Kuban steppe, includes the Maikop people, and represents admixture between steppe people and Mesopotamia.

In 4200 BCE, Danubian Culture (“Old Europe”) was at its peak. Centered in Bulgaria, the Varna cemetery had the most elaborate funerals in the world, richer than anything of the same age in the Near East. Goddess fertility cults with female statues were ubiquitous, suggesting patriarchal control was weak in these societies.

Old Europe collapsed between 4200 and 3900 BCE. More than six hundred tell sites were burned and abandoned in eastern Bulgaria. Steppe material culture appeared in Old Europe just before the collapse.

The colder climate of this period undoubtedly strained the economies of Old Europe. But pervasive evidence of warfare (ubiquitous stone maces), tell fortifications, site abandonment, and massacre-linked mass graves all point to a complementary role of endemic warfare. This would not have been a coordinated military invasion. Small-scale raids and piecemeal migrations did the trick.

The Usatova and Cernavoda I cultures have 49% and 76% CLV ancestry, suggesting they were the product of migration. The Suvorovo-Novodanilovka complex left kurgan graves, which may hint at a CLV connection (the CLV also used kurgans).

The discovery of the CLV people and their migrations provide the first paleogenetic evidence corroborating the Indo-Anatolian hypothesis. Specifically, Lazaridis & Reich (2024) argue for a eastern migration of the CLV people into Anatolia. Before this, Anatolian languages emerged in western Anatolia, prompting Kloekhorst (2023) to hypothesize a western migration from the Balkans. However, the expansion of the Kura-Araxes culture removed any trace of CLV ancestry from eastern Anatolia, which may explain the absence of PIA languages from this region.

And then, in 3500 BCE, the Yamnaya singularity occurred. But first, let’s try to understand what caused the profound success of these particular people.

Towards Nomadic Pastoralism

In severe snowstorms, cattle die quickly. They cannot burrow through the snow, and perish without fodder. But horses are supremely well adapted to the cold grasslands where they evolved. A shift to colder climatic conditions would incentivize the domestication of horses. Just such a shift occurred between 4200 and 3800 BCE. Did horse domestication occur in the Eneolithic?

In modern-day Kazakhstan, the Botai people used domesticated horses in order to more effectively hunt wild equids. The 3500 BCE site featured horse teeth wear consistent with bitting, stables, dairy consumption, and other circumstantial evidence strongly suggestive of Eneolithic husbandry (Outram et al 2009). The Botai relationship with horses may have initially been analogous to reindeer herding tribes. But Botai horses are not the ancestors of modern-day horses (Librado et al 2021), but the smaller Przewalski’s horse (Gaunitz et al 2018).

The Przewalski horse was likely not imported into the Pontic steppe. But the ancestors of modern horses already lived there. Could the Yamnaya have applied such techniques to local equids in the Eneolithic? After the collapse of Old Europe, CLV Cline settlements regularly contain horse bones. Maces with horse heads become common in steppe graves. If horses were not being ridden into the Danube valley, it is difficult to explain their sudden symbolic importance in Old European settlements.

While the status of the horse in the Eneolithic is unclear, EBA Yamnaya exhibit skeletal pathologies consistent with horseriding (Trautmann et al 2023). So “proto-modern” horses likely contribute to the Yamnaya singularity. The horse revolutionized both pastoral economies and also their military efficacy.

With a herding dog, a person on foot can herd ~200 sheep. On horseback with the same dog, one can herd ~500. Larger herds require larger pastures, and the desire for larger pastures would have caused a series of boundary conflicts. Further, horses also make raiding much more profitable. When the indigenous peoples of the North American Plains first began to ride, chronic horse-stealing raids soured relationships even between tribes that had been friendly. Riding also was an excellent way to retreat quickly; often the most dangerous part of tribal raiding on foot was the running retreat after a raid.

The wagon was likely invented in the Near East, and rapidly disseminated to the Yamnaya via the Maikop. This technology greatly expanded the pastoralist niche:

With a wagon full of tents and supplies, herders could take their herds out of the river valleys and live for weeks or months out in the open steppes between the major rivers-the great majority of the Eurasian steppes. Land that had been open and wild became pasture that belonged to someone. Soon these more mobile herding clans realized that bigger pastures and a mobile home base permitted them to keep bigger herds. Amid the ensuing disputes over borders, pastures, and seasonal movements, new rules were needed to define what counted as an acceptable move—-people began to manage local migratory behavior. Those who did not participate in these agreements or recognize the new guest-host institutions became cultural Others, stimulating an awareness of a distinctive Yamnaya identity.

Natural selection in humans is also subject to controversy. Most adaptations take a long time to persist. Given our recent speciation date (~250 kya), Sapiens exhibit remarkable genetic homogeneity (Boyd & Silk 2020). But selective sweeps in humans may be accelerating (Hawks et al 2007), and aDNA reveal at least seven instances of selective sweeps (Matthieson et al 2018). Two of these are relevant to the Yamnaya:

First, the Yamnaya were among the first to evolve lactose persistence (Segurel et al 2020), a genetic adaptation which disseminated with their migration patterns. Lactose persistence has also evolved independently in Africa and other locales, but these variants did not spread as widely (Segurel & Bon 2017). Lactose persistence seems to evolve as an adaptation to pastoralist diet. Paleoproteomic data show dairying became pervasive in the early bronze age (predominantly from sheep), and the Yamnaya show iron deficiency characteristic of heavy milk drinking. Milk processing (converting it into cheeses, yogurts, etc) also reduces the lactose content of milk. LP adaptations complement processing, uplifting its bearers to new caloric opportunities.

Second, the Yamnaya were subject to selection for increased height. There have been three changes in stature trends: a reduction at the advent of agriculture, an increase at the advent of mobile pastoralism, and an increase during the Industrial Revolution. The change in human height 200 years ago is clearly caused by non-genetic changes. But height is 80% heritable, and the genome shows selection for reduced height with the birth of agriculture, and selection for steppe pastoralists. These genetic changes are likely a response to changes in human diet. The Yamnaya simply enjoyed more protein and fat. They were 12-20 cm (5-8 inches) taller than their agriculturalist neighbors!

Sherratt (1983) proposed a revolution in subsistence economics, where pastoralists who had been using animals for their primary products (meat, blood, hides) started capitalizing on secondary products (wool, milk, and muscle power). This secondary products revolution is a nice way of conceptualizing the ascent of the steppe.

The horse and the wagon gave pastoralists an immense economic advantage. The horse and their physical robustness gave them a considerable military advantage. These factors help explain what happened next.

The Yamnaya Singularity

Europe’s farming communities were booming in 3800 BCE. But starting in 3400 BCE, a demographic collapse gripped the subcontinent. The causes of the Neolithic decline are poorly understood. Seersholm et al (2024) found a very high prevalence of plague in early Bronze Age Scandinavia. Proximity to domesticated animals correlates with volume of zoonotic pathogens, which makes a steppe origin of plague plausible. If Yersinia pestis exhibited high lethality, it may help explain the Neolithic decline.

The Yamnaya singularity began 3800 BCE. It did occur within a single generation. But it was sudden. aDNA shows a founder event of a few thousand Yamnaya individuals. We also see dramatic changes in pollen cores. In Sweden, we see the steppe-affiliated Single Grave Culture burning down forests to make grassland for their herds.

We can see the suddenness from aDNA time series. Steppe peoples invaded Britain around 2500 BCE, leading to a 90% replacement of ancestry. The Iberian migration was less totalizing, but it still involved a fairly sudden 40% replacement.

Two of the very earliest Yamnaya migrations were the Afanasievo culture (who spoke Tocharian, discussed above), and also traveled through the Globular Amphora peoples to make the Corded Ware culture. The Corded Ware peoples (haplogroup R1a) received 70-80% ancestry from the steppe. The Bell Beaker peoples (haplogroup R1b) exhibit more cultural than genetic diffusion.

Yamnaya in the eastern steppe were more mobile than the west, an economic difference with interesting implications. The western steppe had more exposure to agriculture, as shown in archaeology and western PIE languages. Western steppe rituals were female-inclusive, eastern steppe rituals were more male-centered. In western religions, the spirit of the hearth was female, and in Indo-Iranian it was male. Western graves had some women, eastern graves had nearly zero.

Chariots and the Indo-Iranians

A millennium later, the Yamnaya hegemony was weakening. A Corded Ware population from Poland was moving east (Saag et al 2021). The first culture on the road to the Ural mountains was the Fatyanovo-Balanovo culture. The next step, east still was the Abashevo culture. These Indo-Iranian people described themselves as Aryan, but the term today has connotations with Aryanism.

The MBA saw the beginning of the aridity crisis, which would ultimately culminate in uninhabitability in the LBA steppe. Deteriorating climate typically exacerbates warfare, and so it was in the Abashevo culture. Weapons were deposited in 10% of EBA Yamnaya graves; in the Abashevo the frequency was closer to 50%. We also see the appearance of many fortified towns. This warfare may also explain the invigorated trade of the region:

Susan Vehik studied political change in the deserts and grasslands of the North American Southwest after 1200 CE, during a period of increased aridity and climatic volatility comparable to the early Sintashta era in the steppes. Warfare increased sharply during this climatic downturn in the Southwest. Vehik found that long-distance trade increased greatly at the same time; trade after 1350 CE was more than forty times greater than it had been before then. To succeed in war, chiefs needed wealth to fund alliance-building ceremonies before the conflict and to reward allies afterward. Similarly, during the climatic crisis of the late MBA in the steppes, competing steppe chiefs searching for new sources of prestige valuables probably discovered the merchants of Sarazm in the Zeravshan valley, the northernmost outpost of Central Asian civilization. Although the connection with Central Asia began as an extension of old competitions between tribal chiefs, it created a relationship that fundamentally altered warfare, metal production, and ritual competition among the steppe cultures.

Sintashta sites were heavily fortified. They were also metallurgic production centers feeding an enormous, high-volume trade route. But Sintashta was the source of two major military shocks. It was here that the modern DOM2 horse was domesticated (with one mutation for lumbar support; the other associated with calmness). And it was here that the spoked-wheel chariot was invented.

In Syria, the Mittani kingdom hired Indo-Iranian chariot mercenaries who in 1500 BCE appear to have usurped the throne and founded a dynasty (Anthony 2012). The dynasty quickly became Hurrian in almost every sense but clung to Indo-Iranian concepts long after its founders faded into history. This is why the deities, moral concepts, and Old Indic language of the Rig Veda are first attested not in India, but in northern Syria.

The Andronovo culture, descendents of the Sintashta, established dominance in this region. They established a trade relationship with the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC). This was the home of fire rituals and soma consumption, which became central elements in Zoroastrian and Hindu religion.

The BMAC genome has no steppe component. Theirs was a cultural contribution. But in 1700 BCE, the Indo-Iranian people migrated into Punjab, bringing Sanskrit with them. The Rig Veda was likely authored in this area around 1300-1500 BCE. The people of the Rig Veda did not live in brick houses and had no cities, although their enemies, the Dasyus, did live in walled strongholds. Chariots were used in races and war; the gods drove chariots across the sky. The chief god Indra is surrounded by a heavenly war band called the maryanna.

This migration into Punjab is evident from aDNA evidence. Modern India shows ~40% ancestry from the steppe, and this genetic contribution is male-biased. Several Out of India theories also try to explain this admixture, but I have not found these alternatives convincing. Two hundred years after the steppe migrations, the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), aka the Harappan Civilization, collapsed. The Ancestral North Indian (ANI) population is a mixture of IVC and steppe peoples (Narasimhan et al 2019).

Was the formidable military of the Indo-Iranians responsible for the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization? The archaeological evidence on the Aryan invasion theory is quite mixed. But the more modest Aryan migration theory receives significant support from paleogenetics.

Steppe ancestry is not distributed equally amongst the ANI – it has a status component. Brahmin ancestry is heavily derived from the Sintashta (Reich et al 2009; Narasimhan et al 2019). Brahmins are among the traditional custodians of Vedic religious texts. The high status of the Vedic migrants may have strong genetic persistence due to endogamy practices of the subcontinent.

There are remarkable parallels between this tale of two subcontinents:

Sex-Biased Demic Expansion

Genetic data cannot tell us how many individuals were alive at any point in time. But it allows estimates of effective population, or those individuals who leave offspring. Karmin et al (2015) found the effective population in women expands very predictably, with demographic booms associated with the initial expansion out of Africa (50 kya), and the invention of agriculture (9 kya). But the effective population in males cratered in the Neolithic, reducing almost in half.

Poznik et al (2016) finds the most intense bursts in male demography are associated with the Yamnaya singularity. Where did all the Neolithic men go?

Demic expansion also occurred during the agricultural revolution. But Goldberg et al (2017) show that these massive migrations were conducted by men and women moving in roughly equal numbers; perhaps families or clans moving together. In contrast, the Yamnaya singularity was a male-biased migration (Saag et al 2017), with a male:female ratio roughly 15:1. Lazaridis & Reich (2017) contest this result; they argue that the signal is distorted by Corded Ware males taking Yamnaya brides.

Several other factors lead me to the male-biased migration hypothesis.

- The Y-chromosome replacement rate substantially exceeds the autosomal rate (e.g., in Iberia, 40% of the genome comes from Yamnaya, but 90% of the haplogroups are from the steppe).

- Burials in Sweden in the Early Bronze Age are predominantly male, with women and children getting more representation in later centuries (Tornberg & Vandkilde 2024).

- Strontium analyses of burials suggest a pattern of local steppe males marrying females from other villages (Sjogren et al 2020).

- Female burial practices are more diverse than that of males.

- Discontinuities in skeletal femur length in the Battle Axe Culture (BAC) are suggestive of a male-biased migration:

Some theorists argue that the genetic data could be explained by differential fertility. I find this difficult to reconcile with the data suggesting male-biased migration and haplogroup turnover.

This pattern is not confined to the Yamnaya. In many of the great admixtures in human history, a central theme has been the coupling of men with social power in one population and women from the other. In African Americans, European ancestry from females is 10% and from males is 38%. In Colombia, European ancestry from females is 10% and from males is 94%. We also see similar patterns in the Bantu migration, and perhaps from the Papuan takeover of the Pacific Islands (Reich 2015). One might view colonialism as the latest incarnation of a deep-seated human behavior – demic expansion.

Genocide or Hypergamy?

It seems that Yamnaya males migrated into Europe fairly rapidly, and Neolithic females began preferentially reproducing with them. But Is this a case of genocide in prehistory, on a scale never before seen? Or was this driven by hypergamy, with females marrying wealthy, prestigious outsiders?

Comparative mythologists have reconstructed several aspects of PIE rituals related to raiding. The Trito myth, which legitimized the cattle raid (“so they might sacrifice the cattle properly”). The transition to manhood was organized around koryos, the warrior brotherhood of young men bound by oath to one another and to their ancestors during a ritually mandated raid. These boys were transformed into warriors by symbolically becoming dogs and wolves through the consumption of their flesh (Anthony & Brown 2017). Kristensen argues that the Yamnaya practiced primogeniture, which would have incentivized non-firstborn males to make a living elsewhere, perhaps via the koryos ritual. This is an ideology of expansion and exploitation.

If the Yamnaya singularity was a genocide, where are all the bodies? Also, military campaigns in the Early Bronze Age are simple anachronisms, and only 10% of Yamnaya were buried with weapons. Further, use-wear analysis has revealed that many Corded Ware axes were primarily used in agriculture (Wentink 2020).

Or it could have been as simple as female choice. We simply do not know. Historical demic expansions are conducted by states executing military campaigns. But these instances often leave a weaker genetic fingerprint. It is difficult to know how migrant males competed for females in prehistory.

Different facets of the Yamnaya express male competition differently. Britain and Iberia had different experiences. The South Asian outcome is more likely to have been bloody, because the Sintashta were more warlike.

Perhaps someday we will understand more.

References

- Allentoft et al (2015). Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia

- Anthony (2012). The horse, the wheel and language: how Bronze-age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world.

- Anthony & Brown (2017). The dogs of war: a Bronze Age initiation ritual in the Russian steppes

- Boyd & Silk (2020). How humans evolved.

- Flannery & Marcus (2012) The creation of inequality.

- Gaunitz et al (2018). Ancient genomes revisit the ancestry of domestic and Przewalski’s horses.

- Goldberg et al (2017). Ancient X chromosomes reveal contrasting sex bias in Neolithic and Bronze Age Eurasian migrations

- Goldberg et al (2017). Reply to Lazaridis and Reich: Robust model based inference of male-biased admixture during Bronze Age migration from the Pontic Caspian Steppe

- Gimbutas (1965). Bronze Age Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe (1965)

- Haak et al (2015). Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe.

- Haak et al (2023). The Corded Ware Complex in Europe in light of current archaeogenetic and environmental evidence.

- Harmanussen (2003).Stature of early Europeans

- Hawks et al (2007). Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution

- Karmin et al (2015). A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture

- Kloekhorst (2023). Proto-indo-anatolian, the “Anatolian split” and the “Anatolian trek”: a comparative linguistic perspective.

- Lazaridis & Reich (2017). Failure to replicate a genetic signal for sex bias in the steppe migration into central Europe

- Lazaridis & Reich (2024). The genetic origin of the Indo-Europeans

- Librado et al (2021). The origins and spread of domestic horses from the Western Eurasian steppes.

- Mathieson et al (2018). Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe.

- Moorjani et al (2013). Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India

- Narasimhan et al (2019). The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia

- Olalde et al (2019). The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years

- Olalde et al (2018). The Beaker Phenomenon and the Genomic Transformation of Northwest Europe

- Pickrell & Reich (2014). Toward a new history and geography of human genes informed by ancient DNA

- Poznik et al (2016). Punctuated bursts in human male demography inferred from 1,244 worldwide Y-chromosome sequences

- Rasmussen et al (). Early divergent strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 years ago

- Reich et al (2009). Reconstructing Indian population history

- Reich (2018). Who we are and how we got here.

- Renfrew (1987). Archaeology and Language: the puzzle of Indo-European origins

- Saag et al (2017). Extensive farming in Estonia started through a sex-biased migration from the Steppe

- Saag et al (2021). Genetic ancestry changes in Stone to Bronze Age transition in the East European plain

- Seersholm et al (2024). Repeated plague infections across six generations of Neolithic Farmers

- Segurel & Bon (2017). On the evolution of lactase persistence in humans.

- Segurel et al (2020). Why and when was lactase persistence selected for? Insights from Central Asian herders and ancient DNA.

- Sherratt (1983). The secondary exploitation of animals in the Old World.

- Taylor & Barron-Ortiz (2024). Rethinking the evidence for early horse domestication at Botai

- Tornberg (2018). Stature and the Neolithic transition – skeletal evidence from southern Sweden

- Tornberg & Vandkilde (2024). Modelling age at death reveals Nordic Corded War paleodemography

- Trautmann et al (2023). First bioanthropological evidence for Yamnaya horsemanship

- Wang et al (2022). The genetic formation of human populations in East Asia

- Wentink (2020). Stereotype: the role of grave sets in Corded Ware and Bell Beaker funerary practices