Missing The Point

Claudia Goldin earned the Nobel Prize for advancing our understanding of women’s labor market outcomes. Her book Career and Family synthesizes her work.

The text can be conceptualized as two separate books:

- The first book (Ch2-7) discusses the demographics of the feminist movement from 1900-2000, which she partitions into five waves.

- The second book (Ch1, 8-10) discusses the gender earnings gap, and her explanation for why this gap persists.

Her analysis in the former was interesting (particularly the discussion on the Pill vs divorce rates). But here, we will focus on the latter.

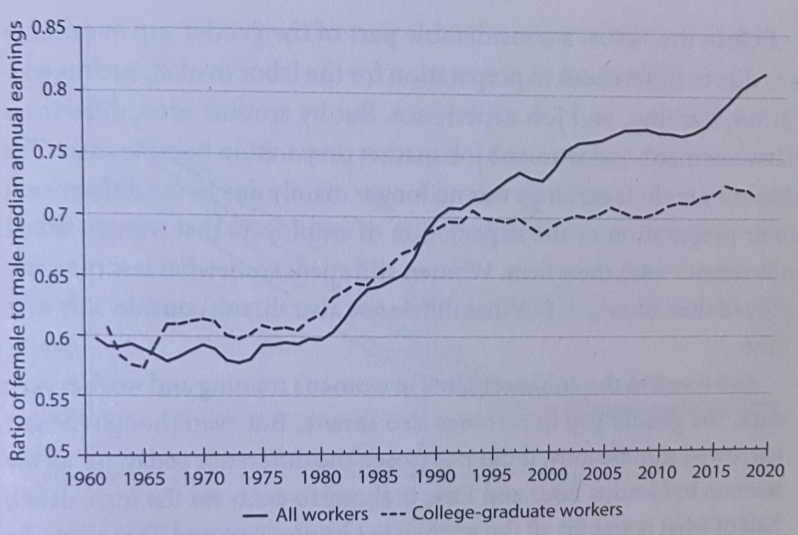

In fact, the gender earnings gap, defined as the difference in medium income across genders, has somewhat lessened over time. But, especially for the college educated, it remains troublingly large:

Before the 1980s, a considerable part of the earnings gap was due to differences in preparation for the labor market, such as education, training, and job experience. But by around 2000, differences between men’s and women’s job market preparation became small.

Goldin begins by reviewing the “standard theories” for the gender earnings gap. They are:

- Occupational Segregation: women simply have different preferences for occupation (these differences may be culturally inherited, or more biological)

- Negotiation Style: women are less competitive and less effective at labor negotiations (these differences may be culturally inherited, or more biological)

- Employer Bias: employers have unconscious biases that add up to substantial impairment to women’s careers.

There are reasons to take these theories seriously:

- Occupational segregation (genders choosing stereotypical professions) explains about one third of the gender gap.

- Women do on average have higher Agreeableness on the Big-Five spectrum, and this personality facet predicts poor occupational outcomes.

- And the implicit association test (IAT) suggests subconscious biases exist.

A whole cottage industry has emerged from these theories. We try to “fix” the women (negotiation training), to “fix” the managers (debiasing).

But the three hypotheses struggle to explain other features of the earnings gap. When you examine the earnings gap longitudinally, things become more clear.

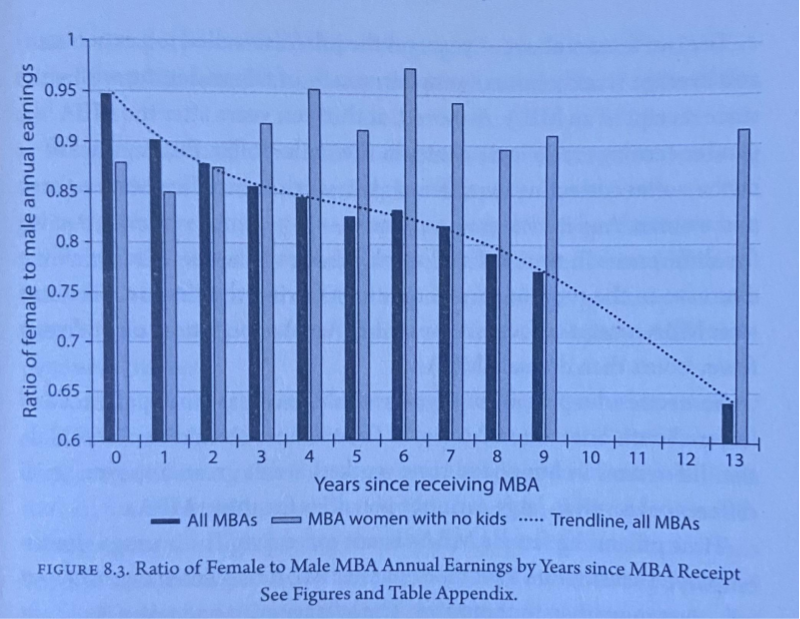

For MBA women with no kids (white bars), the earnings gap begins around 90% and is remarkably stable over time. For MBA women, including those with kids (black bars), the earnings gap steadily declines.This decline usually begins after childbirth.

Occupational segregation may explain the constant 10% gap (white bars). It is harder to explain the larger, ever-growing motherhood-specific gap. Why should negotiation style and managerial paternalism only affect mothers?

In the first five years after the birth, a woman whose spouse was in the top-earning group was 32 percent less likely to be working than if her husband was not. Butwomen who have high-earning husbands but no children put in as many years of employment and hours of work. Why should having a high-earning spouse.only matter for mothers?

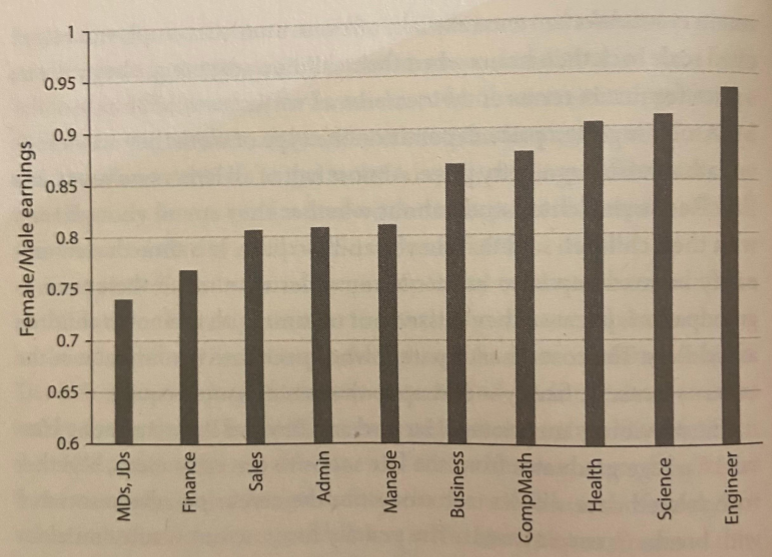

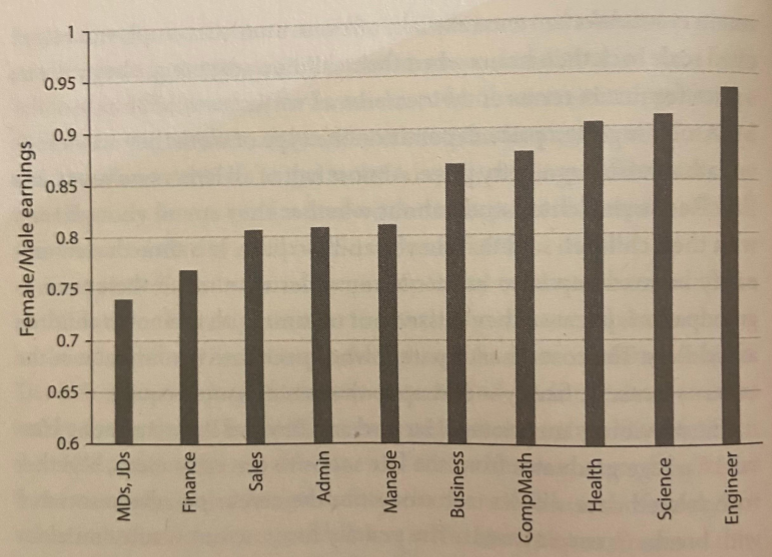

The confusion deepens when you look at the earnings gap across occupations:

Are medicine and law uniquely paternalistic? Are science and engineering culture especially egalitarian?

Time Constraints Explain the Gap

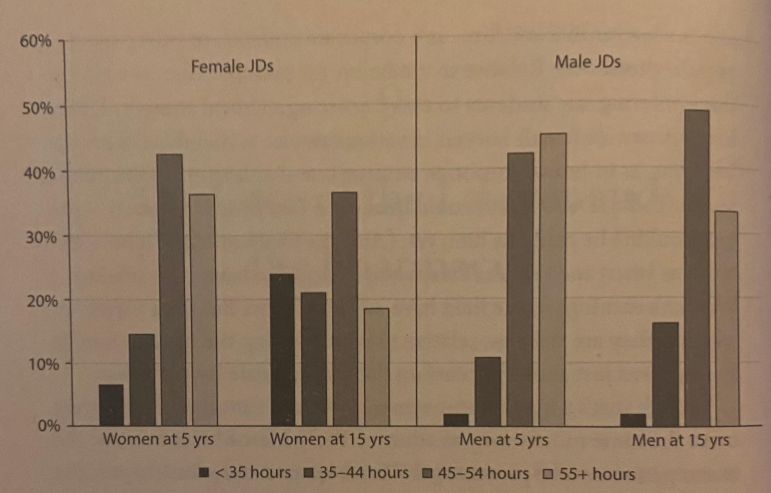

Let’s turn to the legal profession. If you compare men and women lawyers five years after their JD, the number of hours worked is fairly equivalent. But if you take the same survey 15 years in, women are simply working much fewer hours, on average:

A similar trend holds when you consider work setting over time. Females are much more likely to be non-practicing, or not currently employed.

Are women actually receiving lower pay for equal work? Not so much anymore. Discrimination in terms of unequal earnings for the same work for a small fraction of the total earnings gap. Mothers are more likely to work fewer hours, and more likely to take breaks in their careers. According to Goldin, nearly all of the gender earnings gap is mediated by the number of hours worked, and the number of months taken off. The gender gap persists despite there being nearly “equal pay for equal work”.

Let’s return to the earnings gap by occupation.

What differentiates high- from low-inequality occupations? Drawing on the O*NET database, the following occupational properties are predictive of a large earnings gap:

- Contact with others: How much contact with others (by telephone, face-to-face, or otherwise) is required to perform your current job?

- Frequency of decision making: In your current job, how often do your decisions affect other people or the reputation or finances of your employer?

- Time pressure: How often does this job require the worker to meet strict deadlines?

- Structured versus unstructured work: To what extent is this work predefined, rather than allowing the worker to determine tasks, priorities, and goals?

- Establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships: What is the importance of developing cooperative working relationships and maintaining them?

Time-intensive occupations have higher penalties for fewer hours and more frequent sabbaticals. This explains why the earnings gap has not closed much in recent decades. While women are graduating in record numbers, many occupations are becoming more time-intensive over time.

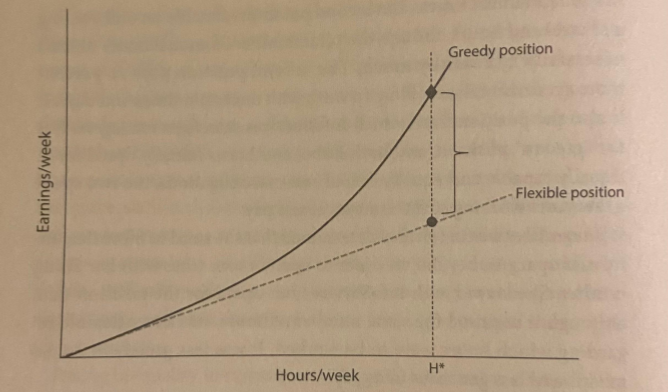

Greedy Work vs Couple Equity

Some jobs offer the same hourly rate to a worker who works 40 hours a week, to those who work 80. This linear payoff has the latter earning twice as much. Call this flexible work. But other jobs offer increasing rates for workers who go above and beyond. On greedy work, one person who works 80-hour weeks will receive significantly more than two people working 40-hour weeks.

Why are certain jobs, like being a lawyer, greedy? If the job involves personal relationships, and the transaction cannot be easily offloaded to a coworker, the price of unavailability and sabbaticals is difficult to manage. The more substitutable the labor, the less greedy the work.

Consider the relationship between couple equity vs earnings gap. Greedy work incentivizes partners to specialize in either career or family. Equal contributions to career and family leave a lot of money on the table. In other words, greedy work is a tax on couple equity. In heterosexual couples, the earnings gap directly reflects couple equity. But greedy work also harms couple equity in same-sex relationships, even if this impact doesn’t drive a (demographically measurable) earnings gap.

Promoting Gender Equality in Practice

On the time boundedness theory, the earnings gap should respond to more affordable childcare, and fathers participating more in childcare. But Goldin is particularly interested in mitigating greedy work. If you remove the tax on couple equity, how much of the earnings gap will evaporate?

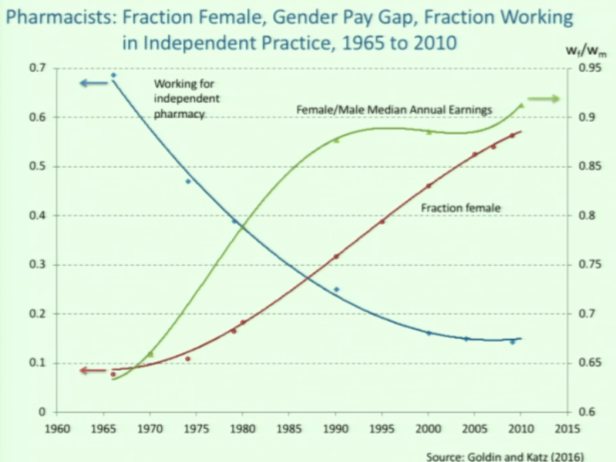

Pharmacy is an example of a profession that moved from greedy to flexible work. Pharmacy used to be very time-intensive:

- You would have a personal relationship with your local pharmacist

- Pharmacists had specialized knowledge of drug combinations, and their skill sets were not easily interchangeable.

- Your local pharmacist owned their own local business

- Local pharmacists were on-call at all hours for late-night emergencies

But all of these time-intensive factors changed in the last four decades. Labor in pharmacy is now substitutable; skill set variance has been reduced by information technology. The corporate takeover of this industry (e.g., Walgreens, CVS) outsourced the time-intensive aspects of business ownership. And emergency pharmacist shops removed the “on-call” expectations for the rest. These changes made the profession move towards linear pay scales (flexible work), and brought the earnings gap from 0.65 to 0.90!

The pharmacy revolution was not engineered to promote gender equality; but we can take the lessons from this industry to achieve this effect. Perhaps the most effective way to combat the earnings gap is to bring the substitutability revolution to other industries. We could encourage a shift from personal bankers to personal banker teams, for example..

Concluding Thoughts

I was hoping to find data directly bearing on the paternalism hypothesis, such as IAT scores by occupation. I wish I had a better understanding of the role negotiation style plays. I tend to agree that the greedy work theory explains the lion’s share of the data, but there are surely other factors in play.

One interesting observation that came out of Goldin’s research:

Two anomalies [to the time-intensivity trend] are those in the health field and in financial operations. Health occupations (such as physical therapists and dietitians) generally have highly specific tasks. They have low levels of gender inequality, but also higher-than-average time demands. On the other end, occupations in financial operations (such as financial advisors and loan officers) have high gender inequality but lower-than-average time demands. Although these occupations do not fit the framework using the five characteristics concerning time demands, they are strongly related to the sixth characteristic: competition. Health occupations have among the lowest degree of competition. Finance occupations have among the highest… Occupations with the greatest income inequality among men have among the largest gender earnings gaps.

This competition factor seems possibly independent of the greedy work theory. I would like to learn more about the effect between-group competition relates to the gender gap.

Recall that patriarchal attitudes (marginalization of women) tend to be accentuated in polities with intensive agriculture. Perhaps the emergence of these attitudes is related to the increase in within-group competition in these political structures. If this speculation is on the right track, I would imagine paternalism and bias to be accentuated for competitive occupations, not just time-intensive ones.

Until next time.