Table Of Contents

- Introduction

- Context

- Overview of CLT

- Insight Scratchpad

- Mental Health

- Skills

- Thinking Modes

- Application

- Self-Diagnosis

- Theory Integration

Introduction

Context

This weekend, I started digging into Construal Level Theory (CLT). This post is ultimately a snapshot of my learning process. It is not comprehensive, nor polished. I have a place for it yet within the theoretical apparatus of my mind & this blog: it contains more questions than answers.

Anyways, I hope you enjoy some of the quotes at least; I found some of them to be extremely thought-provoking. (Unless noted otherwise, quotes are taken from this Psychlopedia review article).

Overview of CLT

Construal Level Theory (CLT) arises from noticing the interchangability of traits. Psychologists have begun to notice two distinct modes of human thought:

- Near Mode: All of these bring each other more to mind: here, now, me, us; trend-deviating likely real local events; concrete, context-dependent, unstructured, detailed, goal-irrelevant incidental features; feasible safe acts; secondary local concerns; socially close folks with unstable traits.

- Far Mode: Conversely, all these bring each other more to mind: there, then, them; trend-following unlikely hypothetical global events; abstract, schematic, context-freer, core, coarse, goal-related features; desirable risk-taking acts, central global symbolic concerns, confident predictions, polarized evaluations, socially distant people with stable traits.

In their review article, theorists Trope and Liberman summarize:

The fact that something happened long ago does not necessarily mean that it took place far away, that it occurred to a stranger, or that it is improbable. Nevertheless, as the research reviewed here demonstrates, there is marked commonality in the way people respond to the different distance dimensions. [Construal level theory] proposes that the commonality stems from the fact that responding to an event that is increasingly distant on any of those dimensions requires relying more on mental construal and less on direct experience of the event. … [We show] that (a) the various distances are cognitively related to each other, such that thinking of an event as distant on one dimension leads one to thinking about it as distant on other dimensions, (b) the various distances influence and are influenced by level of mental construal, and (c) the various distances are, to some extent, interchangeable in their effects on prediction, preference, and self-control.

Insight Scratchpad

Mental Health

After individuals experience a negative event, such as the death of a family member, they might ruminate about this episode. That is, they might, in essence, relive this event many times, as if they were experiencing the anguish and distress again. These ruminations tend to be ineffective, compromising well-being (e.g., Smith & Alloy, 2009).

In contrast, after these events, some individuals reflect more systematically and adaptively on these episodes. These reflections tend to uncover insights, ultimately facilitating recovery (e.g., Wilson & Gilbert, 2008).

When individuals distance themselves from some event, they are more inclined to reflect on this episode rather than ruminate, enhancing their capacity to recover. That is, if individuals consider this event from the perspective of someone else, as if detached from the episode themselves, reflection prevails and coping improves. In contrast, if individuals feel immersed in this event as they remember the episode, rumination prevails and coping is inhibited. Indeed a variety of experimental (e.g., Kross & Aydyk, 2008) and correlational studies (e.g., Ayduk & Kross, 2010) have substantiated this proposition.

When processing trauma, then, inducing abstract construals is desirable.

Arguably, depressed individuals tend to adopt an abstract, rather than concrete, construal. Consequently, memories of positive events are not concrete and, therefore, do not seem salient or recent. Indeed, people may feel these positive events seem distant, highlighting the difference between past enjoyment and more recent distress.

As this argument implies, memory of positive events could improve the mood of depressed individuals, provided they adopt a concrete construal. A study that was conducted by Werner-Seidler and Moulds (2012) corroborates this possibility. In this study, individuals who reported elevated levels of depression watched an upsetting film clip. Next, they were told to remember a positive event in their lives, such as an achievement. In addition, they were told to consider the causes, consequences, and meaning of this event, purportedly evoking an abstract construal, or to replay the scene in their head like a movie, purportedly evoking a concrete construal. As predicted, positive memories improved mood, but only if a concrete construal had been evoked.

In contrast, in the context of clinical depression, inducing concrete construals may be desirable.

In short, an abstract construal may diminish anxiety, but a concrete construal can diminish dejection and dysphoria

Interesting.

Skills

Action identification theory specifies the settings in which abstract and concrete construals–referred to as high and low levels–are most applicable (Vallacher, Wegner, & Somoza, 1989; Wegner & Vallacher, 1986). One of the key principles of this theory is the optimality hypothesis. According to this principle, when tasks are difficult, complex, or unfamiliar, lower level action identifications, or a concrete construal, are especially beneficial. When tasks are simple and familiar, higher level action identifications, or an abstract construal, are more beneficial.

To illustrate, when individuals develop a skill, such as golf, they should orient their attention to tangible details on how to perform some act, such as “I will ensure my front arm remains straight”. If individuals are experienced, however, they should orient their attention to intangible consequences or motivations, such as “I will outperform my friends”

Applying CLT to games. Perhaps I could use this while playing chess. 🙂

Similarly, as De Dreu, Giacomantonio, Shalvi, and Sligte (2009) showed, a more abstract or global perspective may enhance the capacity of individuals to withstand and to overcome obstacles during negotiations. If individuals need to negotiate about several issues, they are both more likely to be satisfied with the outcome of this negotiation if they delay the most contentious topics. To illustrate, when a manager and employee needs to negotiate about work conditions, such as vacation leave, start date, salary, and annual pay rise, they could begin with the issues that are vital to one person but not the other person. These issues can be more readily resolved, because the individuals can apply a technique called logrolling. That is, the individuals can sacrifice their position on the issues they regard as unimportant to gain on issues they regard as very important. Once these issues are resolved, trust improves, and a positive mood prevails. When individuals experience this positive mood, their thoughts focus on more abstract, intangible possibilities, which can enhance flexibility. Because flexibility has improved, they can subsequently resolve some of the more intractable issues.

Applying CLT to negotiation. This would seem to overlap the latitudes of acceptance construct from social judgment theory.

Thinking Modes

When individuals adopt an abstract construal, they experience a sense of self clarity (Wakslak & Trope, 2009). That is, they become less cognizant of contradictions and conflicts in their personality. Presumably, after an abstract construal is evoked, individuals orient their attention towards more enduring, unobservable traits (cf. Nussbaum, Trope, & Liberman, 2000). As a consequence, individuals become more aware of their own core, enduring qualities–shifting attention away from their peripheral, and sometimes conflicting, characteristics.

This matches my experience.

Attentional tuning theory (Friedman & Forster, 2008), which is underpinning by construal level theory, was formulated to explain the finding that an abstract construal enhances creativity thinking and a concrete construal enhances analytic thinking (e.g, Friedman & Forster, 2005; Ward, 1995).

Makes me wonder whether metaphor (engine of creative thinking) is powered by System1 processes.

Applications

Self-Diagnosis

Over time, therefore, people tend to behave politely when they feel a sense of distance. According to construal level theory, this distance coincides with an abstract construal. Therefore, politeness and an abstract construal should be associated with each other.

I tend to be very polite…

An abstract construal can also amplify the illusion of explanatory depth–the tendency of individuals to overestimate the extent to which they understand a concept (Alter, Oppenheimer, & Zemla, 2010)

I often suffer from this particular emotion.

When individuals adopt an abstract construal, they tend to be more hypocritical. That is, they might judge an offence as more acceptable if they, rather than someone else, committed this act.

I am guilty of this more often than most.

Taken together, one could make the case that I, Kevin, gravitate towards “far mode” (i.e., finding distance between my concept of self & my surroundings).

Theory Integration

To evoke a concrete construal, participants are instructed to specify an exemplar of each word, such as poodle or Ford.

An interesting link between CLT and Machery’s Heterogeneity Hypothesis.

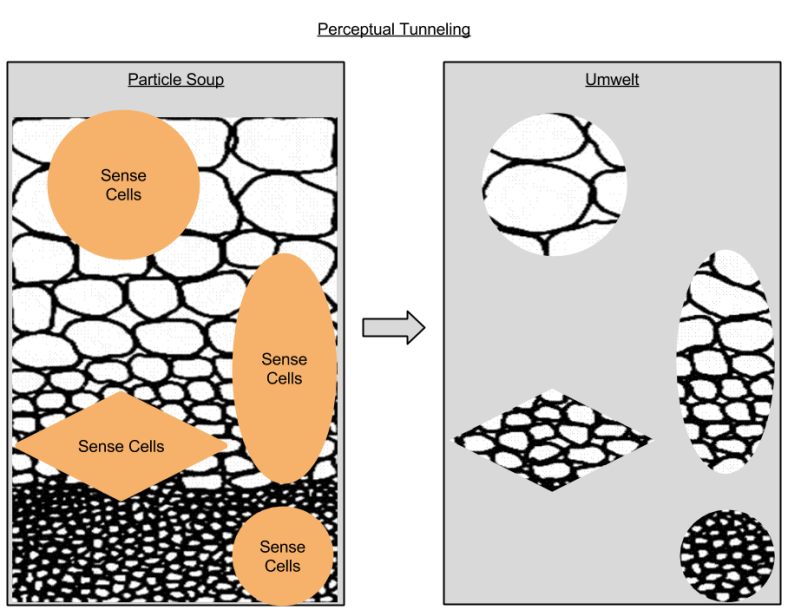

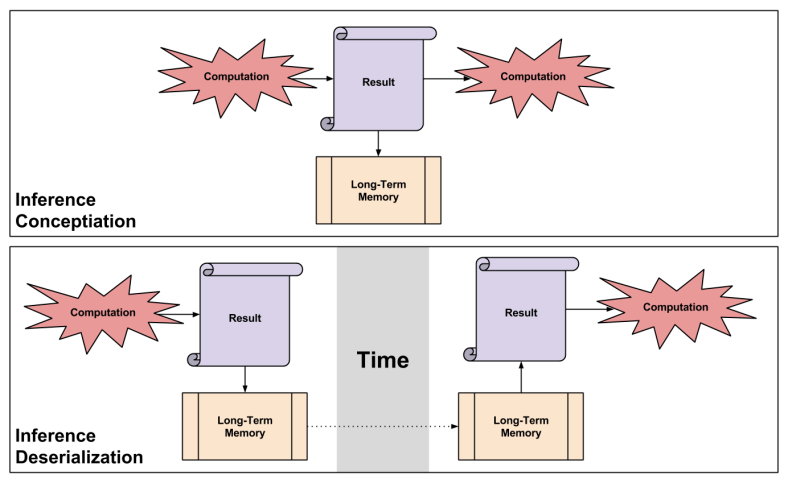

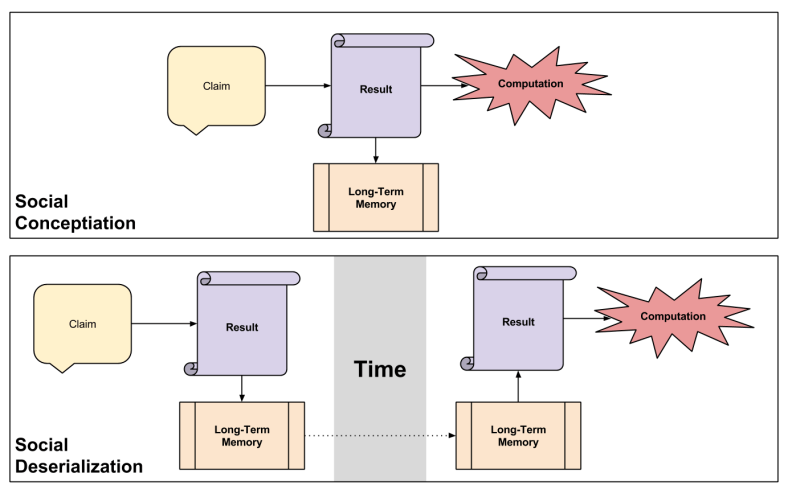

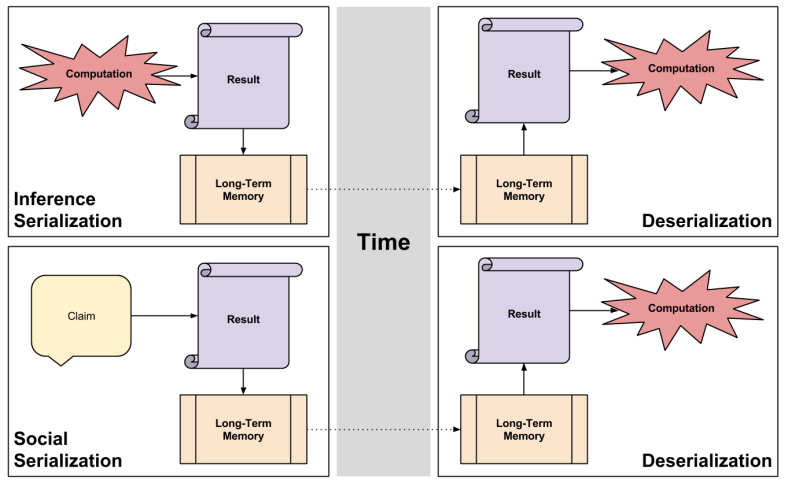

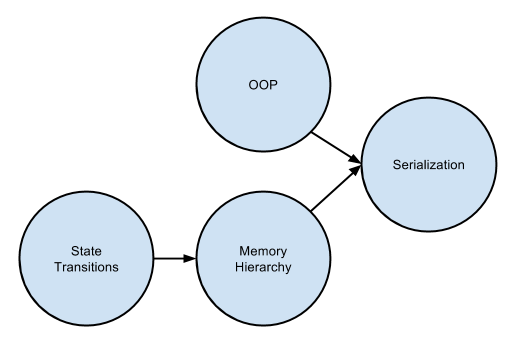

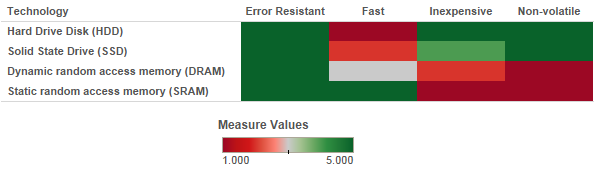

In my deserialization series (e.g., Deserialized Cognition), I gestured towards two processing modes: authority and inference. Perhaps this could be simply hooked into CLT, with Near Mode triggering social processing, and Far Mode triggering inference processing.

Most crucially of all, I need to see how CLT can be reconciled with dual process theory (DPT). One weakness of dual-processing theory, in my view, is in its difficulties producing an explanation for the context-dependent cognitive styles of Eastern cultures, versus the context-independence cognitive styles of Western cultures. Perhaps difficulties such as these could be dissolved by knitting the two theories together.

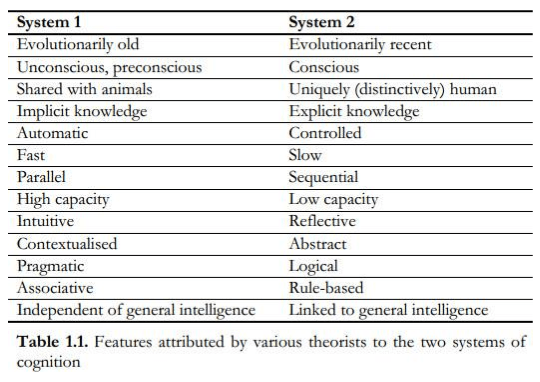

But how to begin stitching? If you’ll recall, dual-process theory is also grounded in, motivated by, dissociations:

Notice the partial overlap: both CLT and DPT claim ownership of the “contextualized vs. abstract” dimension. But despite this partial overlap, when writing these theories back into mental architecture diagrams, the dissociations are produced by radically different things. System2 is – arguably – the product of a serialized “virtual machine” sitting on top of our inborn evolutionary-old modules. But Near Mode and Far Mode, they seem to be the product of an identity difference vector: how far a current thing is from one’s identity. (In fact, CLT might ultimately prove a staging grounds for investigations into the nature of personality). But this all makes me wonder how identity integrates into our mental architecture…

The entire process of integrating CLT and DPT is a formidable challenge… I’m unclear the extent to which the social psychological literature has already pursued this path. I also wonder whether any principles can be extracted by such integration attempts. Both CLT and DPT are – at their core – behavioral property bundlers – finding commonalities & interchangeabilities within human behaviors and descriptions. In general, do property-bundling theories produce sufficient theoretical constraint? And how does one, in principle, move from property-bundling to abducing causal mechanisms?

Takeaway

As a parting gift, a fun summary from Overcoming Bias: