Part Of: Demystifying Life sequence

Followup To: Population Genetics

Content Summary: 1400 words, 14 min read

How Natural Selection Works

Consider the following process:

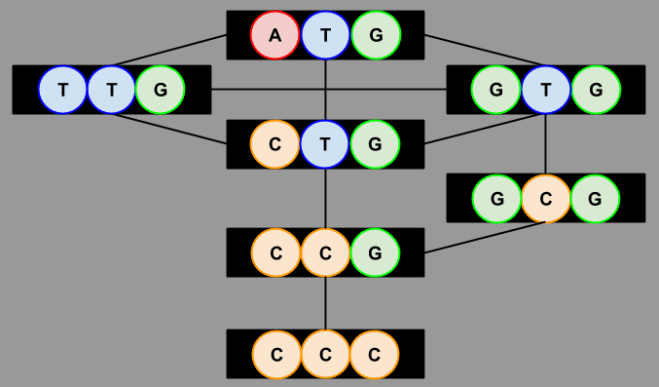

- Organisms pass along traits to their offspring.

- Organisms vary. These random but small variations trickle through the generations.

- Occasionally, the offspring of some individual will vary in a way that gives them an advantage.

- On average, such individuals will survive and reproduce more successfully.

This is how favorable variations come to accumulate in populations.

Let’s plug in a concrete example. Consider a population of grizzly bears that has recently migrated to the Arctic.

- Occasionally, the offspring of some grizzly bear will have a fur color mutation that renders their fur white.

- This descendent will on average survive and reproduce more successfully.

Over time, we would expect increasing numbers of such bears to possess white fur.

Biological Fitness Is Height

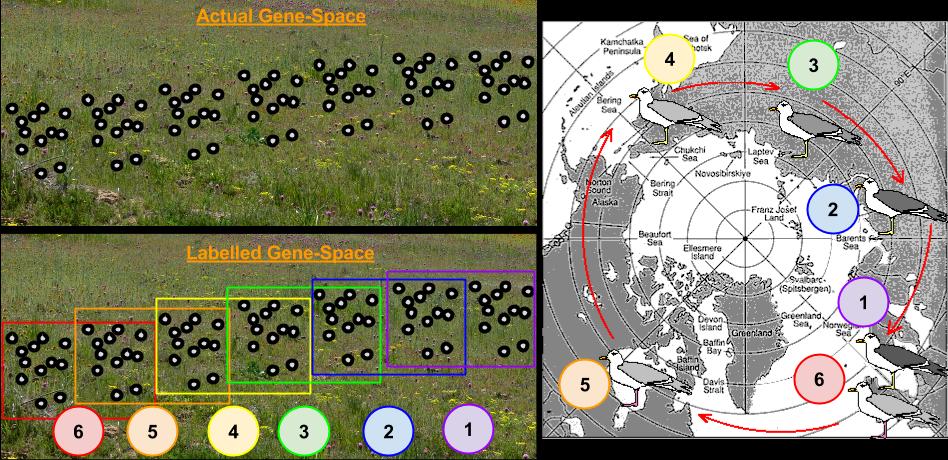

The above process is straightforward enough, but it lacks a rigorous mathematical basis. In the 1940s, the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis enriched natural selection by connecting it to population genetics, and its metaphor of Gene-Space. Recall what we mean by such a landscape:

- A Genotype Is A Location.

- Organisms Are Unmoving Points

- Birth Is Point Creation, Death Is Point Erasure

- Genome Differences Are Distances

Onto this topography, we identified the following features:

- A Species Is A Cluster Of Points

- Species Are Vehicles

- Genetic Drift is Random Travel.

In order to understand how natural selection enriches this metaphor, we must define “advantage”. Let biological fitness refer to how how many fertile offspring an individual organism leaves behind. An elephant with eight grandchildren is more fit than her neighbor with two grandchildren.

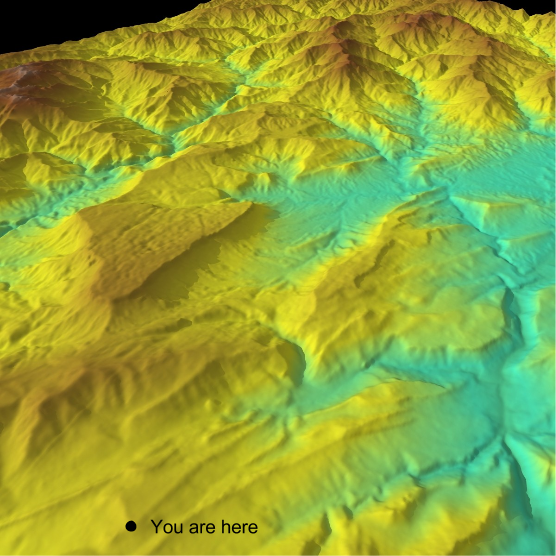

Every organism achieves one particular level of biological fitness. Fitness denotes how well-suited an organism is to its environment. Being a measure of organism-environment harmony, we can view fitness as defined for every genotype. Since we can define some number for every point in gene-space, we have license to introduce the following identification:

- Biological Fitness Is Height

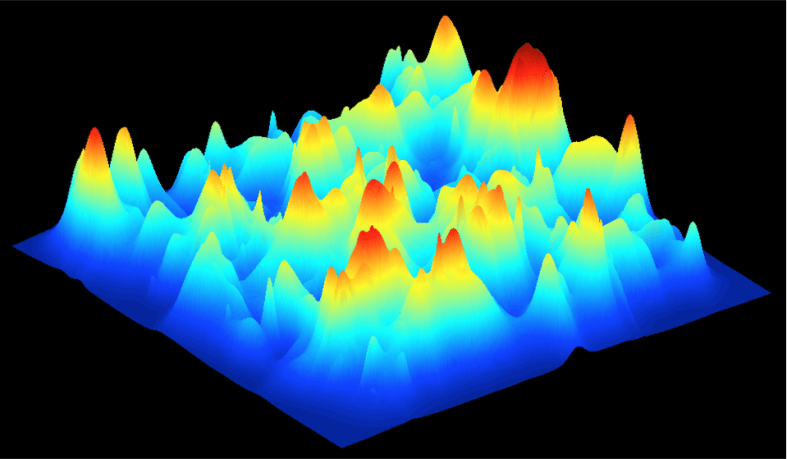

Here is one possible fitness landscape (image credit Bjørn Østman).

We can imagine millions of alien worlds, each with its own fitness landscape. What is the contours of Earth’s?

Let me gesture at three facts of our fitness landscape, to be elaborated next time:

- The total volume of fitness is constrained by the sun. This is hinted at by the ecological notion of carrying capacity.

- Fitness volume can be forcibly taken from one area of the landscape to another. This is the meaning of predation.

- Since most mutations are harmless, the landscape is flat in most directions. Most non-neutral mutations are negative, but some are positive (example).

Natural Selection As Mountain Climbing

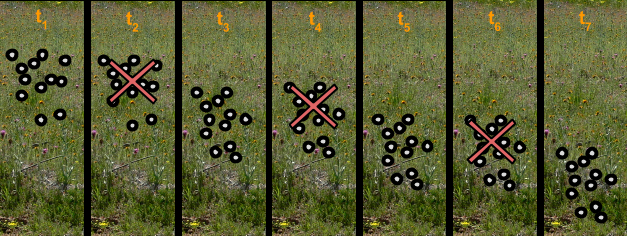

A species is a cluster of points. Biological fitness is height. What happens when a species resides on a slope?

The organisms uphill will produce comparatively more copies of themselves than those downhill. Child points that would have been evenly distributed now move preferentially uphill. Child points continue appearing more frequently uphill. This is locomotion: a slithering, amoeba-like process of genotype improvement.

We have thus arrived at a new identification:

- Natural Selection Is Uphill Locomotion

As you can see, natural selection explains how species gradually become better suited to their environment. It is a non-random process: genetic movement is in a single direction.

Consider: ancestral species of the camel family originated in the American Southwest millions of years ago, where they evolved a number of adaptations to wind-blown deserts and other unfavorable environments, including a long neck and long legs. Numerous other special designs emerged in the course of time: double rows of protective eyelashes, hairy ear openings, the ability to close the nostrils, a keen sense of sight and smell, humps for storing fat, a protective coat of long and coarse hair (different from the soft undercoat known as “camel hair”), and remarkable abilities to take in water (up to 100 liters at a time) and do without it (up to 17 days).

Moles, on the other hand, evolved for burrowing in the earth in search of earthworms and other food sources inaccessible to most animals. A number of specialized adaptations evolved, but often in directions opposite to those of the camel: round bodies, short legs, a flat pointed head, broad claws on the forefeet for digging. In addition, most moles are blind and hard of hearing.

The mechanism behind these adaptations is selection, because each results in an increase in fitness, with one exception. Loss of sight and hearing in moles is not an example of natural selection, but of genetic drift: blindness wouldn’t confer any advantages underground, but arguably neither would eyesight.

Microbiologists in my audience might recognize a strong analogy with bacterial locomotion. Most bacteria have two modes of movement: directed movement (chemotaxis) when its chemical sensors detect food, and a random walk when no such signal is present. This corresponds with natural selection and genetic drift, respectively.

Consequences Of Optimization Algorithms

Computer scientists in my audience might note a strong analogy to gradient descent, a kind of algorithm. In fact, there is a precise sense in which natural selection is an optimization algorithm. In fact, computer scientists have used this insight to design powerful evolutionary algorithms that spawn not one program, but thousands of programs, rewarding those with a comparative advantage. Evolutionary algorithms have proven an extremely fertile discipline in problem spaces with high dimensionality. Consider, for example, recent advances in evolvable hardware:

As predicted, the principle of natural selection could successfully produce specialized circuits using a fraction of the resources a human would have required. And no one had the foggiest notion how it worked. Dr. Thompson peered inside his perfect offspring to gain insight into its methods, but what he found inside was baffling. The plucky chip was utilizing only thirty-seven of its one hundred logic gates, and most of them were arranged in a curious collection of feedback loops. Five individual logic cells were functionally disconnected from the rest— with no pathways that would allow them to influence the output— yet when the researcher disabled any one of them the chip lost its ability to discriminate the tones…

It seems that evolution had not merely selected the best code for the task, it had also advocated those programs which took advantage of the electromagnetic quirks of that specific microchip environment. The five separate logic cells were clearly crucial to the chip’s operation, but they were interacting with the main circuitry through some unorthodox method— most likely via the subtle magnetic fields that are created when electrons flow through circuitry, an effect known as magnetic flux. There was also evidence that the circuit was not relying solely on the transistors’ absolute ON and OFF positions like a typical chip; it was capitalizing upon analogue shades of gray along with the digital black and white.

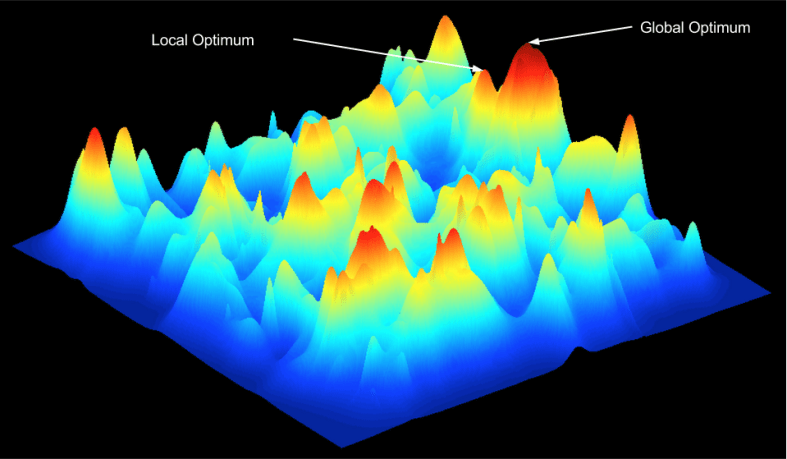

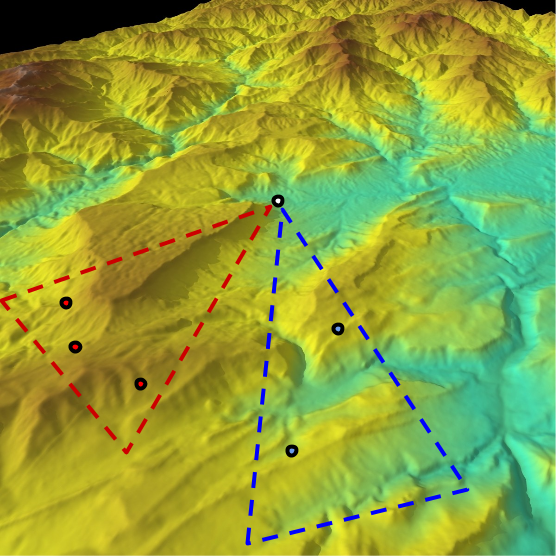

In gradient descent, there is a distinction between global optima and local optima. Despite the existence of an objectively superior solution, the algorithm cannot get there due to its fixation with local ascent.

This distinction also features strongly in nature. Consider again our example of camels and moles:

Given such a stunning variety of specialized differences between the camel and the mole, it is curious that the structure of their necks remains basically the same. Surely the camel could do with more vertebrae and flex in foraging through the coarse and thorny plants that compose its standard fare, whereas moles could just as surely do with fewer vertebrae and less flex. What is almost as sure, however, is that there is substantial cost in restructuring the neck’s nerve network to conform to a greater or fewer number of vertebrae, particularly in rerouting spinal nerves which innervate different aspects of the body.

Here we see natural selection as a “tinkerer”; unable to completely throw away old solutions, but instead perpetually laboring to improve its current designs.

Takeaways

- In the landscape of all possible genomes, we can encode comparative advantages as differences in height.

- Well-adapted organisms are better at replicating their genes (in other words, none of your ancestors were childless).

- Viewed in the lens of population genetics, natural selection becomes a kind of uphill locomotion.

- When view computationally, natural selection reveals itself to be an optimization algorithm.

- Natural solution can outmatch human intelligence, but it is also a “tinkerer”; unable to start from scratch.