Content advisory: if you know how chess pieces move, this article should be accessible to you.

Table Of Contents

- Introduction

- Why Does This Article Exist?

- Notation & Scoring

- Ratings & Phases

- How Chess Games Are Won

- How To Understand A Chess Position

- Introducing My Starting Position

- Towards Board Analysis

- Why Are Goals Important In Chess?

- Finding A Goal

- Anticipating The Other Player

- How Does Chess Become Less Mysterious?

- How To Evaluate A Chess Decision

- Introducing My Solution

- Analyzing Decision Outcome

- Towards Judgment

- Conclusion

Introduction

Why Does This Article Exist?

I have played chess professionally since I was a teenager. Today, I want to share with you this private world. I will use a correspondence game (multiple days per move, instead of seconds per move) to do this. We will together walk through several decisions made by myself and my opponent.

My reasons for exploring chess are not contained to sharing an interesting piece of my life. I hope to use this material to explore certain themes useful in attempts to integrate artificial intelligence and cognitive psychology. But that’s for later. For now, if you leave this article with a better idea of how chess players make decisions, I will be content.

In a former life, I taught chess to hundreds of six-year-olds. While clearly my readership here will need more guidance, I will do my best to accomodate. 😉

Notation & Scoring

The 64 squares of the chessboard have names. Rows (also called ranks) are 1-8, columns (also called files) are a-h.

Piece symbols are:

- King: K

- Queen: Q

- Rook: R

- Bishop: B

- Knight: N

- Pawn: [blank]

Algebraic notation allows us to communicate chess moves. To do this, we simply combine the two symbols discussed above. There exist a few caveats regarding captures (x means capture) and when more than one piece can land on a particular square (originating rank or file is appended). Examples:

- Ne4 would represent a Knight that moved to the e4 square.

- gxf5 would represent a pawn on g4 that captures something on the f5 square.

- Rec8 would represent a Rook on e8 moving to c8, if another Rook could have moved to the same location.

Chess players like to keep track of how large their army is, compared to their opponent. However, it is not enough to count pieces: a queen is certainly worth more than a pawn. The following scoring system was instead invented, to facilitate comparison between different combinations of pieces:

- King: [infinite points]

- Queen: 9 points

- Rook: 5 points

- Bishop: 3 points

- Knight: 3 points

- Pawn: 1 point

Ratings & Phases

The chess community tracks playing strength with a fairly complex rating scheme: ELO ratings. Absolute beginners tend to perform around a 400 rating, those who play regularly-yet-casually trend towards 900, and world champions hover around 2800. The relationship between effort and rating is non-linear: almost all chess players will tell you that more time is required to rise from 1900 to 2100, than from 1200 to 1900. (My rating is currently 1903.)

The game of chess is traditionally divided into three separate phases: the opening, the middlegame, and the endgame. Since all games start from the same position, chess players have gradually accumulated common wisdom in the form of opening lines. Professional chess players will often memorize the first 5-15 moves of nearly every possible (interesting) game: to fail to memorize these lines is to risk independently trying to reconstruct them, failing to compute the optimal sequence, and finding yourself at a disadvantage (for this reason, tournament preparation can be quite competitive, and taxing). Similarly, endgames typically feature very few pieces, its complexity becomes tractable, and memorization returns to the fore as an extremely important tool.

It is a very normal sight to see grandmaster chess players play their first opening moves quickly, consume hours lost in thought during the middlegame, and as soon the endgame result is clear either resign or offer a draw – the end result being nearly inevitable. Arguably, the middlegame retains the most interest in the face of such professionalism. Why? Because our best minds have failed to tame its complexities.

How Chess Games Are Won

Chess games are won by checkmate: i.e., attacking the enemy King in a way it cannot escape. But checkmating is not an unpredictable “happening”. After your tenth chess game or so, you will start to notice that the cumulative strength of one’s army is predictive of the final outcome. This is why the scoring system above was developed: to allow for the prediction of victory.

Most absolute beginners have little difficulty accepting the scoring system. The next realization, however, takes significantly longer to arrive. You see, for most players in chess, material advantages come about by accident. An understanding of attack and defense, the eyesight needed to anticipate “tricks”: these take a long time to mature (such mistakes feel like dropping a negative sign in a long algebra problem).

It takes a long time for the average human to transcend mistake-avoidance in chess. If you keep at it, your idea of how material advantages come about will slowly evolve. The key moment comes when both players are mature enough to avoid material-shedding mistakes. Despite this newfound sophistication, you are not guaranteed to avoid losing material. Why? Well… every so often, your opponent will make a series of attacking threats, and you will find yourself simply unable to generate an adequate defense response. Here come the critical question: how can one player be able to outpace his opponent in this way?

The answer lies in positional advantages, a concept much more subtle than material advantages. There are very many ways for a player to possess a positional advantage. These positional features include:

- Pawn structure. Some pawn configurations are more stable and defensible than others.

- Space. Some pawn configurations allow a player relatively more room to maneuver.

- King safety. How many defensive resources does a player have near his King?

- Piece development. At what rate has one managed to bring pieces into the fight?

- Piece cohesion. Are one’s pieces working together well?

- Initiative. Who is making more threats, and dictating the course of the game?

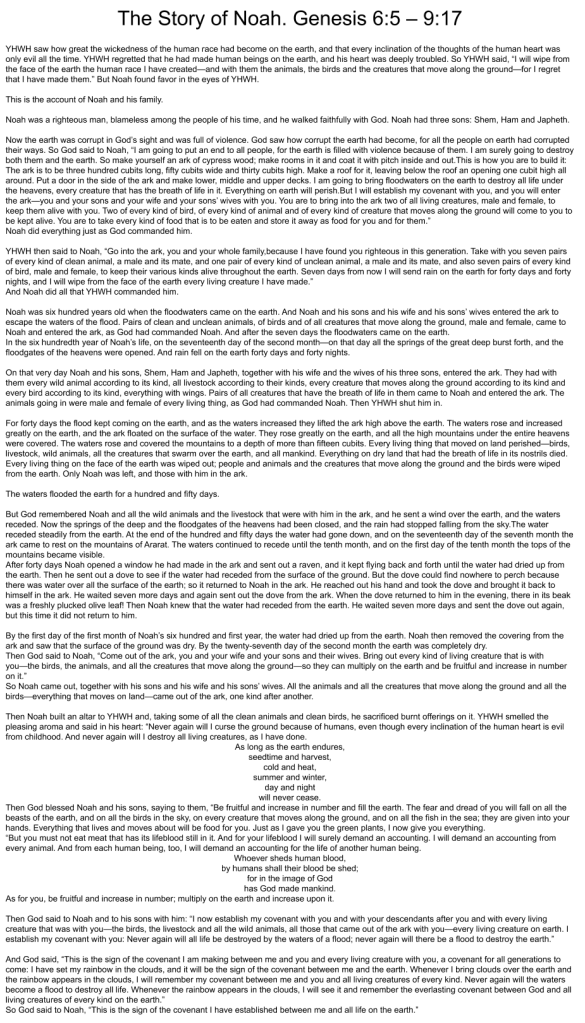

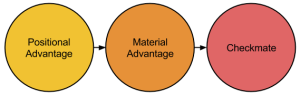

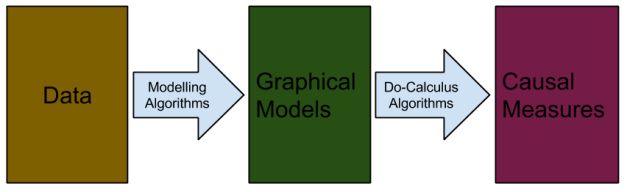

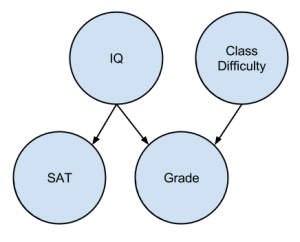

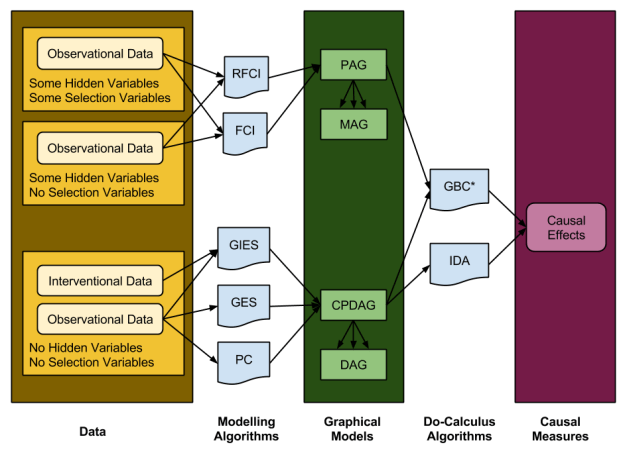

The above discussion can, perhaps, be represented with the following (rather crude) diagram:

How To Understand A Chess Position

Introducing My Starting Position

With these preliminaries out of the way, I can now to introduce you to real gameplay!

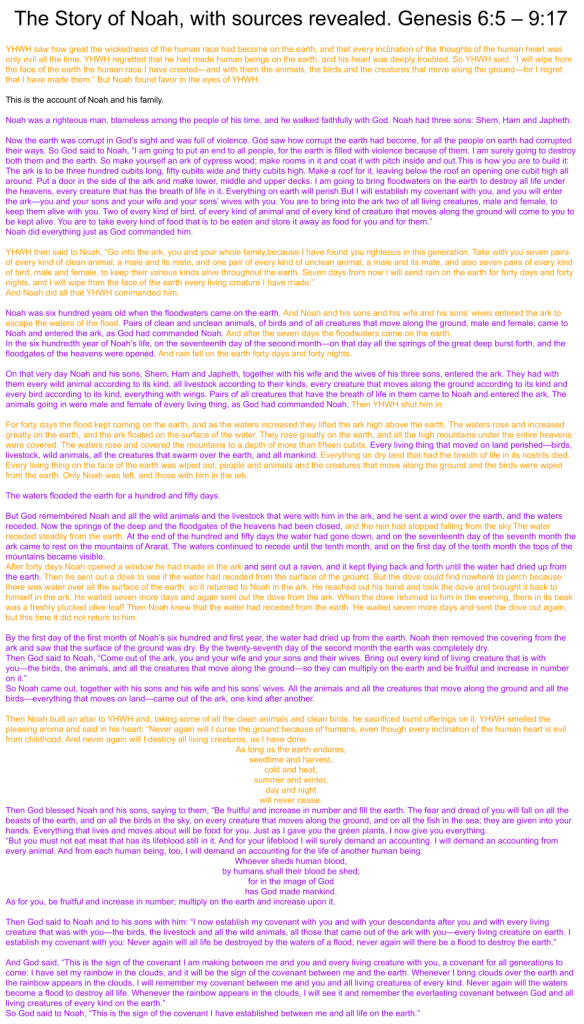

Consider the following. Each player have played 19 moves, I am playing as White, and it is my turn.

Towards Board Analysis

Taking what we learned about How Chess Games Are Won, let us now conduct a material analysis and a positional analysis.

Black and White possess an equal number of pawns, knights, bishops, rooks, queen. Materially, then, the game is even. This equality is likely to persist: White shouldn’t play Bxe7 because Black can recapture Rxe7, and Black comes out ahead 2 pts. Similarly, if Black were to capture Bxc3, this isn’t necessarily wrong, but after Qxc3 material remains even (both players have lost 3 pts).

But chess is not just about the size of your army, it is how the army is being used. Let us scan through our positional features using a -5 to 5 scale (-5 is a strong Black advantage, 5 is a strong White advantage, 0 is equality):

- Pawn structure: +0.2. (Both sides pawn’s coordinate well, and are not particularly vulnerable to attack.)

- Space. +2.0. (My pawns have advanced, on average, 1 or 2 steps further.)

- King safety. -1.8. (My King doesn’t have a guardian Bishop, and my pawns are further advanced.)

- Piece development. +0.2. (No pieces are “stuck at home” anymore.)

- Piece cohesion. +0.8 (Black’s Bb7 and Rc8 aren’t particularly useful, White’s Rooks and Bishops are better coordinated.)

- Initiative. +0.0 (Neither player has significant control over the pace of the game.)

I want to emphasize here that the above numbers are subjective: I made them up. But, as we shall see later, quantifying my “gut feelings” turns out to be extremely useful.

Let us also notice that most pieces, on both sides, are not attacking the pieces of the other player. There are simply too many pawns in the way. It turns out that, in clogged positions such as these, play tends toward aggressive pawn moves that serve to clear a path for one’s pieces. Such “jailbreaking” often happens after subtle maneuvering, where each player tries to get her pieces better positioned to capitalize on their coming freedom.

Why Are Goals Important In Chess?

Why should play tend to gravitate towards aggressive pawn moves? Consider what happens if one player contents himself with moving his pieces behind his wall of pawns. His opponent could then dictate when and where to bring the fight to the other player.

This kind of argument illustrates a central theme in chess: successful players tend to think in terms of goals. Once a goal is selected, a plan must then be constructed, to move the current situation towards the desired one. Let’s now turn to my starting position to see what this means, concretely.

Finding A Goal

White desires to find a goal from his current position. We’ve already agreed that aggressive pawn moves represent useful goals. But where?

Is White best advised to locate a Queenside strategy? Can White aggressively advance his a- or b- pawn on the Queenside? Not immediately: such moves (a5 and b4) would lose material. What if White were to, say, play Na2 – thus making possible a later b4 pawn advance (since both Queen and Knight can now recapture). This plan does not seem especially promising: after a future b4 cxb4, Black’s Queen and a Rook will suddenly be attacking our pawn on c4!

How about a Kingside strategy, with White advancing his g and/or h pawns? Too risky: White’s King is already rather exposed. White’s biggest space advantage is in the center of the board, so let’s now restrict our attention there. The two candidates are: e5 and f5.

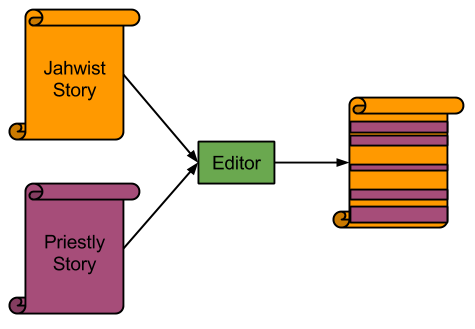

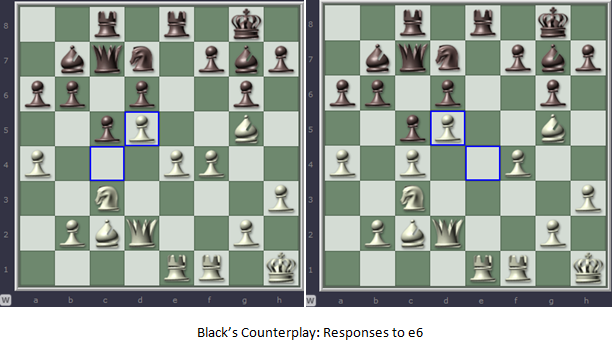

Can White afford to advance his pawn to e5 (left image)? Do the math! 20. e5 dxe5 21. fxe5 Nxe5 22. Rxe5 Bxe5. Black comes out way ahead (if you didn’t do the math, take my word for it :P).

So 20. e5 is no good. How 20. f5 (right image)? This is safe: gxf5 is met by exf5 – equality. But such a move allows Black’s Knight to land in the e5 square (Ne5), previously impossible when the f4 pawn could capture such a daring Knight. So, White seems in a quandary: he would like to increase his space advantage… but both pawn moves that could accomplish this seem deficient.

We know that White should be playing in the center. Perhaps White’s goal should be: arrange his pieces so that e5 does not lose material.

Anticipating The Other Player

What goals should Black try to pursue? Can we anticipate counterplay?

On the Queenside, b5 qualifies as a pawn break. For now, it loses material. Let us imagine a future position where it does not lose material. Is such a goal worthy of Black’s time? Perhaps: it will take a while to get his pieces ready, but it would give Black an attack.

On the Kingside, Black will hesitate to advance his pawns, due to safety concerns for his King.

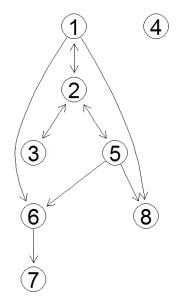

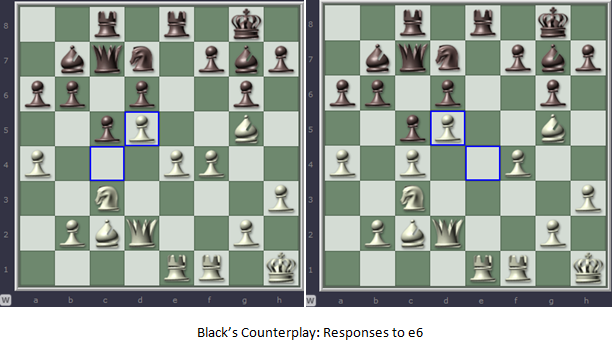

In the Center, f5 will ultimately weaken Black’s pawn structure. But what should happen if Black plays e6? White may hesitate to capture: dxe6 fxe6 gives up White’s space advantage. So, Black will have the opportunity to capture exd5, after which White will face a choice. The following image imagines this choice (after 20. Bc2 e6 21. Kh1 exd5):

Recapturing cxd5 (left image) preserves his central dominance, but now White must fear a very powerful Queenside attack: Black may now play c4 and Nc5. This threat is sufficiently scary: White will probably recapture exd5 (right image).

This possibility adds some urgency to White’s plan: if Black is given opportunity to play e6, he will bring the game closer to equality by relieving spatial pressure by trading pawns and Rooks. Worse still, such a trade would prevent White from meeting his goal to play e5!

How Does Chess Become Less Mysterious?

Pause for a minute, and take stock of how you feel. You probably feel lost, a bit like you’ve wandered into a foreign land. It turns out that almost everyone encountering this material has a similar experience. But this feeling of confusion is important, so let’s try to understand it.

Perhaps the strangeness comes from unfamiliarity. Or, perhaps my arguments lack specificity! Would you become able to confidently teach this new understanding of chess to a friend, dear reader, if I had only made it more lengthy, more precise?

I doubt it. Such an “improvement” feels funny once you consider how chess is learned. Playing strength does not improve once playing strength by argumentation (conscious reasoning) alone: experience must play a role. Let us name this observation, that language can express chess knowledge more easily than it can teach it, representational language asymmetry.

I have watched literally hundreds of games play out from this exact pawn structure, and I have developed a very sharp intuition for what kinds of strategies matter in this type of position. In this four-pawns-Benoni, of course White must not find a goal on the Queenside. Likewise, the solution I employ below seems shocking at first… but it is a highly stylized pattern that I have, again, evaluated in the context of dozens of other games.

I have noticed representational language asymmetry before, while teaching ESL last year. In my view, learning chess is a lot like learning a language: personal practice and learning from the example of others is the most efficient way forward.

How To Evaluate A Chess Decision

Dear reader, where have we landed? We now know that White would like to break through in the center. We also know that White is in crisis: he would like to act before Black plays e6, but all available pawn breaks lose material. What should White do?

Rather than motivate how I addressed this challenge, let me simply show you. 🙂

Introducing My Solution

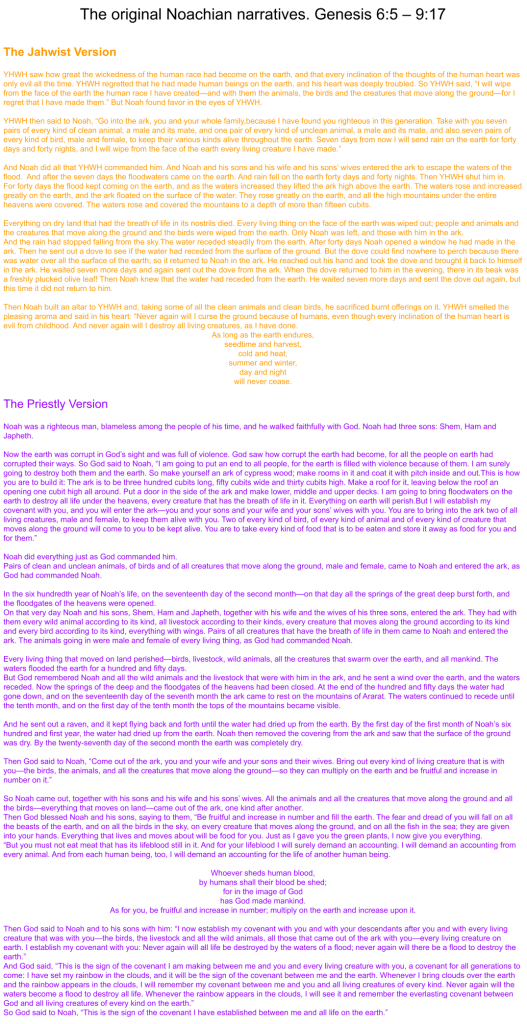

20. e5 dxe5

21. f5

Analyzing Position Outcome

Material analysis:

- I have lost one pawn (but no more: 21 …gxf5 22. Rxf5 is simply a trade).

Positional analysis:

- Pawn structure: -0.5 (Black’s e5 pawn is now unopposed by any White pawn, but the e7 pawn is no discouraged from moving)

- Space. +3.5. (My pawn on f5 really cramps his style! )

- King safety. +0.5. (My pawn on f5 is looking to remove one of Black’s King’s protective pawns)

- Piece development. +0.0. (No real changes in this feature.)

- Piece cohesion. +4.5 (My Rooks are now active, my Knight and Bishops are now well-positioned, his Bishop is now blocked).

- Initiative. +2.0 (White has started to dictate which aspects of the game are worthy of attention.)

Towards Judgment

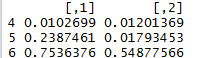

We can now directly compare before and after! Copying the two sets of numbers I produced above:

|

Starting Score |

End Score |

Difference |

| Material: Points |

+0.0 |

-1.0 |

-1.0 |

| Position: Pawn structure |

+0.0 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

| Position: Space |

+2.0 |

+3.5 |

+1.5 |

| Position: King safety |

-1.5 |

+0.5 |

+2.0 |

| Position: Piece development |

+0.0 |

+0.0 |

+0.0 |

| Position: Piece cohesion |

+1.0 |

+4.5 |

+3.5 |

| Position: Initiative |

+0.0 |

+2.0 |

+2.0 |

We see that I have accepted losses in material and pawn structure, in exchange for gains in space, King safety, piece cohesion, and initiative. But how are we to know whether such a complex tradeoff is a decision worth making?

Recall our vocabulary words: positional advantage, material advantage. Now is the time to admit cumulative advantage into our corpus. If we wish to speak intelligibly about chess decisions, we simply must compress our analysis features into a single number (there is no room for incommensurability in chess!). Here’s how I view the cumulative effect of my decision:

|

Starting Score |

End Score |

Difference |

| Estimated Total |

+0.4 |

+0.6 |

+0.2 |

Dear reader, how am I to convince you that such a total score is correct? Will I provide you with cute mathematics? A weighted average over the above features?

I cannot provide such a thing, because I do not possess it. The truth is, I don’t consciously use mathematical reasoning while playing chess! Rather, all of my valuations are written in the currency of intuitions, of emotional valence. And that is a deep and mysterious thing.

Conclusion

Takeaways

Congratulations! You survived to the end of this article. We have covered a lot of ground. 🙂

I’ll close by recapping the points I most want you to remember:

- Positional advantages cause material advantages, which in turn lead to checkmate.

- Positional advantages are composed of many different features, such as pawn structure or piece cohesion.

- Goals are vital to success.

- Evaluating a chess position is a largely subconscious experience, one that requires experience.

Enjoy the +100 bump in chess rating I just gave you! 😉