Part Of: Demystifying Sociality sequence

Content Summary: 1500 words, 15min read

Anosognosia

It is unfortunate to experience illness. It is strange to fail to recognize illness within oneself. Anosognosia is the name for this inability. A few examples:

Example 1. In a letter to his friend Lucilius, Seneca (40 CE) described a woman who obstinately denied her blindness.“….You know that Harpestes, my wife’s fatuous companion, has remained in my home as an inherited burden….This foolish woman has suddenly lost her sight. Incredible as it might appear, what I am going to tell you is true: She does not know she is blind. Therefore, again and again she asks her guardian to take her elsewhere because she claims that my home is dark…..It is difficult to recover from a disease if you do not know to be ill….”.

Example 2. After a right-hemisphere stroke, she lost movement in her left arm but continuously denied it. When the doctor asked her to move her arm, and she observed it not moving, she claimed that it wasn’t actually her arm, it was her daughter’s. Why was her daughter’s arm attached to her shoulder? The patient claimed her daughter had been there in the bed with her all week. Why was her wedding ring on her daughter’s hand? The patient said her daughter had borrowed it. Where was the patient’s arm? The patient “turned her head and searched in a bemused way over her left shoulder”.

Spend enough time with these patients, and it becomes clear that their problem is not cognitive dissonance. No, the delusion has a much deeper, subterranean, hold on their mental lives. These patients freely generate explanations for their illness-related behavior (“I can’t walk around because the house is dark”, “The unmoving arm isn’t mine, it is my daughters”). These explanations are not examples of dishonesty. They are genuine perceptions of a misfiring mind. The word for these honest lies is confabulation.

If you’re anything like me, you’ll find such epistemic fences a bit unsettling. Is it possible our entire species is entertaining a similar delusion that increases biological fitness? Do we actually have four fingers but are collectively convinced that little fingers exist?

Split Brain Patients

The vertebrate brain has two hemispheres. Some neural functions are bilateral: visual processing occurs in both right and left hemisphere (one per eye). Other functions are unilateral: language processing is usually left-lateralized (with the exceptions tending to be left-handed). The advantages & disadvantages of lateralization of brain function is an active research area.

In neurotypical animals, there exist traverse fibers (commissures) which integrate information between the hemispheres. The corpus callosum is the overwhelmingly dominant bridge between hemispheres:

- Corpus Callosum: 250 million fibers

- Anterior commissure: 0.5 million fibers

- Posterior commissure: 0.5 million fibers

- Habenula commisure: 0.1 million fibers

Split brain patients are those that have had their corpus callosum severed. These patients tend to exhibit selfhood fracturing: each hemisphere constitutes a largely autonomous entity with its own beliefs and desires.

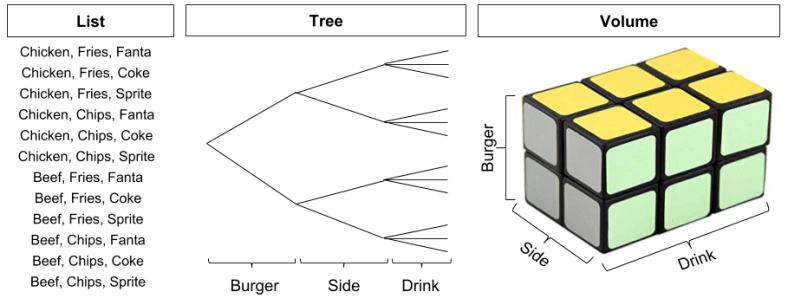

Present the left hemisphere with a picture of a chicken claw, and the right with a picture of a wintry scene. Now show the patient an array of cards with pictures of objects on them, and ask them to point (with each hand) something related to what they saw. The hand controlled by the left hemisphere points to a chicken, the hand controlled by the right hemisphere points to a snow shovel. So far so good.

But what happens when you ask the patient to explain why they pointed to those objects in particular? The left hemisphere is in control of the verbal apparatus. It knows that it saw a chicken claw, and it knows that it pointed at the picture of the chicken, and that the hand controlled by the other hemisphere pointed at the picture of a shovel. Asked to explain this, it comes up with the explanation that the shovel is for cleaning up after the chicken. While the right hemisphere knows about the snowy scene, it doesn’t control the verbal apparatus and can’t communicate directly with the left hemisphere, so this doesn’t affect the reply. The patient instead confabulates.

What did ”the patient” think was going on? This is a wrong question. Once you know what the left hemisphere believes, what the right hemisphere believes, and how this influences organism behavior, then you know all that there is to know.

Gazzaniga has described this propensity of patients to confabulate reasons for the behavior of the right brain as the left-brain apologist. The left hemisphere functions as an interpreter, a lawyer, a press secretary:: it justifies behavior to make the organism look good. V.S Ramachandran, drawing on observations that right-brain lesions disproportionately produce delusions, claims the existence of a right-brain revolutionary. It is the failure some module in the right hemisphere that causes anosognosia: the left-brain apologist to go unchecked: confabulation exacerbated by delusion.

Confabulation in Neurotypicals

We have so far explored confabulation in patients with brain damage. Do neurotypical, everyday people produce “honest lies”?

We confabulate all the time.. We just don’t realize that we are.

In Telling More Than We Can Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes, Nisbett & Wilson (1977) review hundreds of studies, across dozens of disciplines. Their evidence admits a theme: people’s attempts to explain their behavior is almost always unhelpful in identifying the important factors influencing their decisions. Let me briefly review four example findings.

Study 1: Insufficient Justification.

Zimbardo et al (1969) ask participants to accept a series of painful shocks while performing a learning task. Participants were split into two groups:

- Adequate Justification (“nothing will be learned unless shocks administered again”)

- Inadequate Justification (“I’m curious to see what happens”)

Who suffers less?

→ The Inadequate Justification group. This group learns much more quickly, and admit lower galvinic skin response (lower “fight or flight”).

Why do they suffer less?

→ These people were given a poor justification for continuing, and yet they continued anyway. To explain their own behavior, they generate intrinsic motivation for continuing. (As an aside, this phenomenon is similar to the overjustification effect).

Do they know that they suffer less?

→ No! Subjective reports of pain were the same across groups.

Study 2: Attribution Effect

Storms & Nisbett (1970) ask insomnia-suffering participants to sleep under observation. Participants were split into two groups:

- Arousal Attribution: placebo given, claimed to cause restlessness, alertness

- Control: no placebo administered

Who falls asleep more quickly?

→ Arousal Attribution group (28% faster).

Why do they fall asleep more quickly?

→ Attribution of restlessness to placebo, rather than cognitive factors.

Do they know why they fall asleep more quickly?

→ No! More than 80% of patients would not attribute sleep improvement to pill, even after the experiment being explained to them.

Study 3: Counterattitudinal Advocacy

Bem & McConnell (1970) ask participants for their view on a political topic. Then ask they write an essay against their own view. Participants were split into two groups:

- Coercion: bribed to write the essay

- Freedom: led to believe they had a choice

Who changes their position after writing the essay?

→ Freedom group.

Why do they change?

→ Difficult to explain writing that essay, unless they wanted to.

Do they know that they changed their position?

→ No! In contrast to the Coercion group which had accurate memories, those whose opinions had changed failed to remember their previous position.

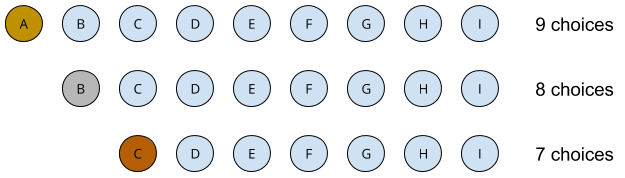

Study 4: Choice Blindness

Johannson et al. (2005) ask participants to evaluate which of two female faces was more attractive. Researchers then hand subjects the face they had chosen, asking them to explain the motives behind their choice. Participants were split into two groups:

- Switch: used a sleight-of-hand trick to switch the photos, showing viewers the face they had not chosen.

- Control: show the face they had chosen

Does the Switch group notice the change?

→ Most don’t. ⅔ of participants believe they had chosen the other face.

Did those who didn’t notice explain of their (non-)choice?

→ Without missing a step. They happily explained why they preferred the face they had actually rejected, inventing reasons like “I like her smile” even though they had actually chosen the solemn-faced picture.

Putting It All Together

Confabulation is “honest lying”: communicating an untruth, while earnestly believing in its veracity.

- Anosognosia patients cannot admit that they are paralyzed. When asked to explain their inability to move, they confabulate answers.

- Split brain patients similarly confabulate explanations for the behavior of the non-linguistic right hemisphere.

- Confabulation is not merely a medical curiosity. Confabulation is everywhere: most self-reports are utterly useless. Some evidence includes:

- Insufficient Justification: people didn’t notice when they were suffering less

- Attribution Effect: people failed to understand the reason why they slept better

- Counterattitudinal Advocacy: after people change their minds, they fail to remember they ever thought differently

- Choice Blindness: once tricked into thinking they chose something different, people are happy to explain their reasons.

Why do human beings confabulate so often? How can we be such utter strangers to ourselves? We shall explore these questions next time. Until then!