Part Of: Analysis sequence

Content Summary: 1000 words, 10 min read

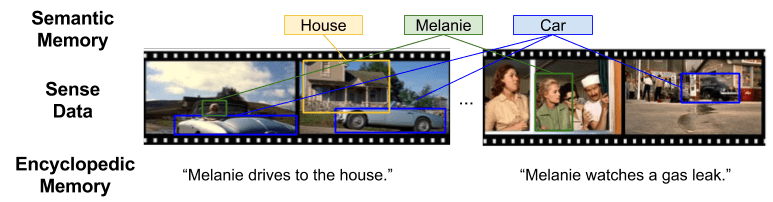

Motivating Example

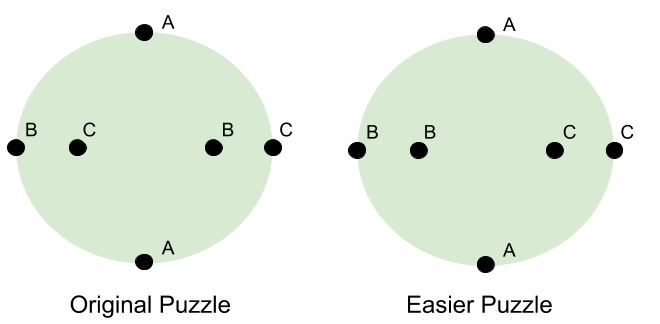

Can you draw three lines connecting A to A, B to B, and C to C? The catch: the lines must stay on the disc, and they cannot intersect.

Here are two attempts at a solution:

Both attempts fail. In the first, there is no way for the Bs and Cs to cross the A line. In the second, we have made more progress… but connecting C is impossible.

Does any solution exist? It is hard to see how…

Consider a simplified puzzle. Let’s swap the inner points B and C.

In the new puzzle, the solution is easy: just draw straight lines between the pairs!

To understand where this solution breaks down, let’s use continuous deformation (i.e., homeomorphism) to transform this easier puzzle back to the original. In other words, let’s swap point B towards C, while not dropping the “strings” of our solution lines:

Deformation has led us to the solution! Note what just happened: we solved an easy problem, and than “pulled” that solution to give us insight into a harder problem.

As we will see, the power of continuous deformation extends far beyond puzzle-solving. It resides at the heart of topology, one of mathematics’ most important disciplines.

Manifolds: Balls vs Surfaces

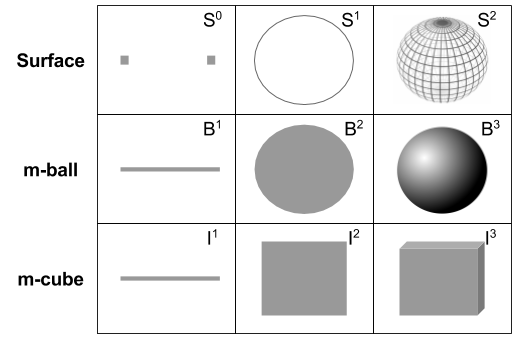

The subject of arithmetic is the number. Analogously, in topology, manifolds are our objects. We can distinguish two kinds of primitive manifold: balls and surfaces.

These categories generalize ideas from elementary school:

- A 1-ball

is a line segment

- A 2-ball

is a disc

is a circle

is a sphere

Note the difference between volumes and their surfaces. Do not confuse e.g., a disc with a circle. The boundary operation makes the volume-surface relationship explicit. For example, we say that

.

Note that surfaces are one dimension below their corresponding volume. For example, a disc resides on a plane, but a circle can be unrolled to fit within a line.

Importantly, an m-ball and an m-cube are considered equivalent! After all, they can be deformed into one another. This is the reason for the old joke:

A topologist cannot tell the difference between a coffee cup and a donut. Why? Because both objects are equivalent under homeomorphism:

If numbers are the objects of arithmetic, operations like multiplication act on these numbers. Topological operations include product, division, and connected sum. Let us address each in turn.

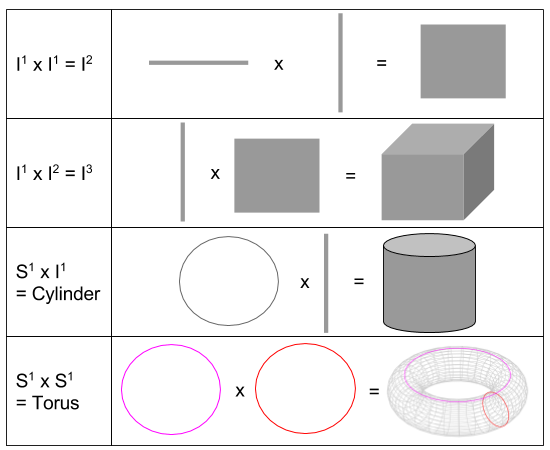

On Product

The product (x) operation takes two manifolds of dimension m and n, and returns a manifold of dimension m+n. A couple examples to whet your appetite:

These formulae only show manifolds of small dimension. But the product operation can just as easily construct e.g. a 39-ball as follows:

How does product relate to our boundary operator? By the following formula:

This equation, deeply analogous to the product rule in calculus, becomes much more clear by inspection of an example:

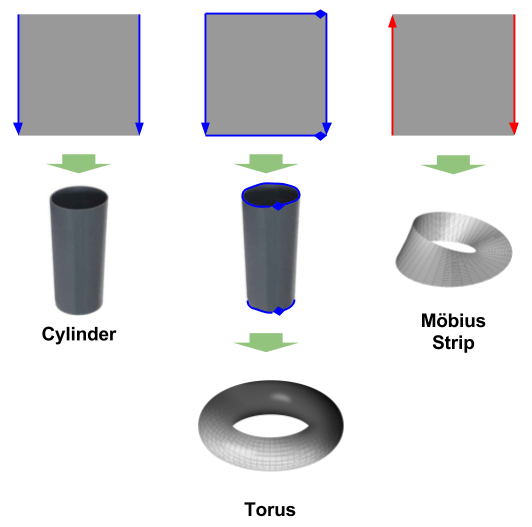

On Division

Division ( / ) glues together the boundaries of a single manifold. For example, a torus can be created from the rectangle :

We will use arrows to specify which edges are to be identified. Arrows with the same color and shape must be glued together (in whatever order you see fit).

Alternatively, we can specify division algebraically. In the following equation, x=0 means “left side of cylinder” and x=1 means right side:

The Möbius strip is rather famous for being non-orientable: it neither has an inside nor an outside. As M.C. Escher once observed, an ant walking on its surface would have to travel two revolutions before returning to its original orientation.

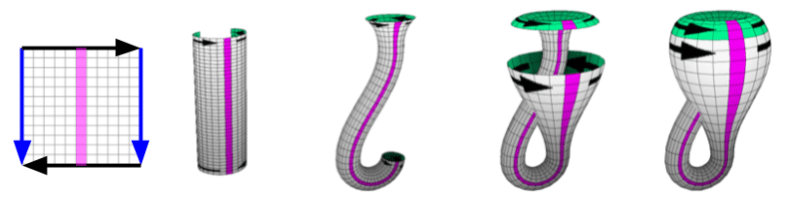

More manifolds that can be created by division on . To construct a Klein bottle by division, you take a cylinder, twist it, and fold it back on itself:

In our illustration, there is a circle boundary denoting the location of self-intersection. Topologically, however, the Klein bottle need not intersect itself. It is only immersion in 3-space that causes this paradox.

Our last example of division is the real projective plane

. This is even more difficult to visualize in 3-space, but there is a trick: cut

again. As long as we glue both pieces together along the blue line, we haven’t changed the object.

The top portion becomes a Möbius strip; the bottom becomes a disc. We can deform a disc into a sphere with a hole in it. Normally, we would want to fill in this hole with another disc. However, we only have a Möbius strip available.

But Möbius strips are similar to discs, in that its boundary is a single loop. Because we can’t visualize this “Möbius disc” directly, I will represent it with a wheel-like symbol. Let us call this special disc by a new name: the cross cap.

The real projective plane, then, is a cross cap glued into the hole of a sphere. It is like a torus; except instead of a handle, it has an “anomaly” on its surface.

These then, are our five “fundamental examples” of division:

On Connected Sum

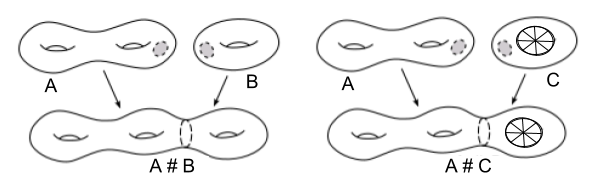

Division involves gluing together parts of a single manifold. Connected sum (#), also called surgery, involves gluing two m-dimensional manifolds together. To accomplish this, take both manifolds, remove an m-ball from each, and identify (glue together) the boundaries of the holes. In other words:

Let’s now see a couple examples. If we glue tori together, we can increase the number of holes in our manifold. If we attach a torus with a real projective plane, we acquire a manifold with holes and cross-cuts.

Takeaways

- Topology, aka. “rubber sheet geometry”, is the study of malleable objects & spaces.

- In topology, manifolds represent objects in n-dimensional space.

- Manifolds either represent volumes (e.g., disc) and boundaries (e.g., circles)

- Manifolds are considered equivalent if a homeomorphism connects them.

- There are three basic topological operations:

- Product (x) is a dimension-raising operation (e.g., square can become a cube).

- Division (/) is a gluing operation, binding together parts of a single manifold.

- Connected sum (#) i.e., surgery describes how to glue two manifolds together.

Related Materials

This post is based on Dr. Tadashi Tokeida’s excellent lecture series, Topology & Geometry. For more details, check it out!