Part Of: Causal Inference sequence

Content Summary: 800 words, 8 min reading time

Counterfactuals

Imagine you are a doctor investigating the effects of a new drug for cancer treatment:

- A large number of patients enroll in the trial.

- For each patient, you may administer the drug, or a placebo.

- For each patient, you record whether the outcome is death or survival (cancer remission).

Let’s sharpen the above account by defining variables across it:

- N patients enroll in the trial.

- Let X represent applied treatment. Placebo application is X=0; drug application is X=1.

- Let Y represent patient outcome. Patient death is Y=0; patient survival is Y=1.

How many patients should we give the drug to? If we give the placebos to all patients, and all of them die, does that mean that our drug works? Of course not! Next, consider the situation where we give the drug to all patients, and all of them live. May we now conclude that the drug is effective in this scenario? Not necessarily: perhaps we have simply encountered a particularly lucky group of human beings.

Imagine next a world where we could acquire answers to any question we dare ask. Here, how would you go about determining the causal effect of our drug?

If a patient dies via the placebo, wouldn’t it be nice if we could rewind time, and observe whether the drug saved their lives (see whether the drug helps this individual)? If a patient dies via the drug, wouldn’t it be nice if we could rewind time and see whether they die via the placebo (perhaps they are beyond help)? In an ideal world, we could rewind time and acquire answers to such what if questions.

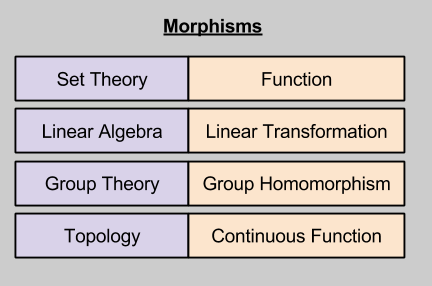

For formal name for what-if models of causality are known as counterfactuals. And counterfactual theories of causation are just one location is a vast, turbulent landscape of the West’s struggle over causation. The first time I wandered into Wikipedia’s survey of causal reasoning, my head was throbbing for hours. But let me spare you an attempt to make sense out of the philosophical implications of counterfactuals, and merely paint a formalism.

An Outcome Taxonomy

We require two more variables:

- Let Y0 represent patient outcome after placebo administration. Thus, Y0=1 means placebo patient lives.

- Let Y1 represent patient outcome after drug administration. Thus, Y1=0 means drugged patient dies.

There are only four possible types of patient:

Translating back into English:

- Patients of type “Never Recover” will die if given the drug, but will also die if given a placebo.

- Patients of type “Helped” will survive if given the drug, but will die if given a placebo.

- Patients of type “Hurt” will die if given the drug, but will live if given a placebo.

- Patients of type “Always Recover” will live if given the drug, but will also live if given a placebo.

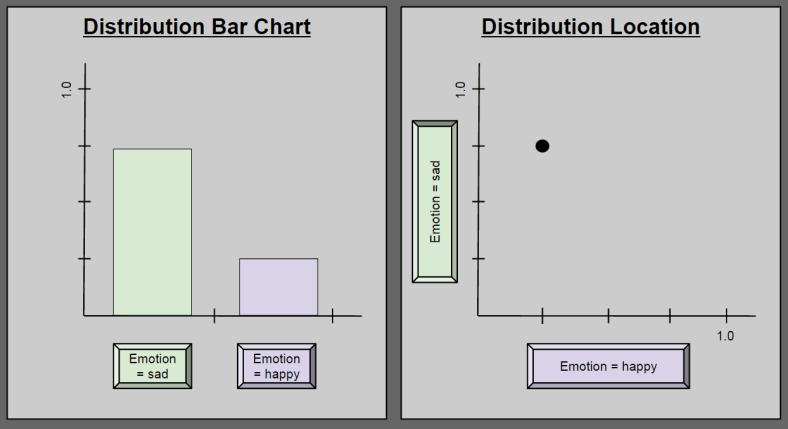

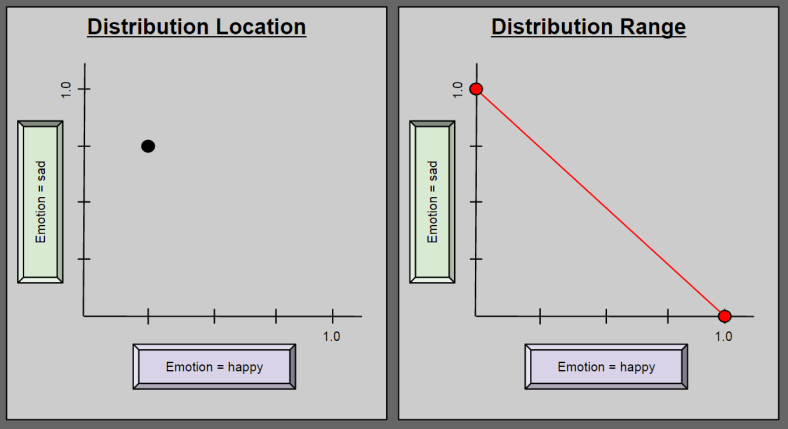

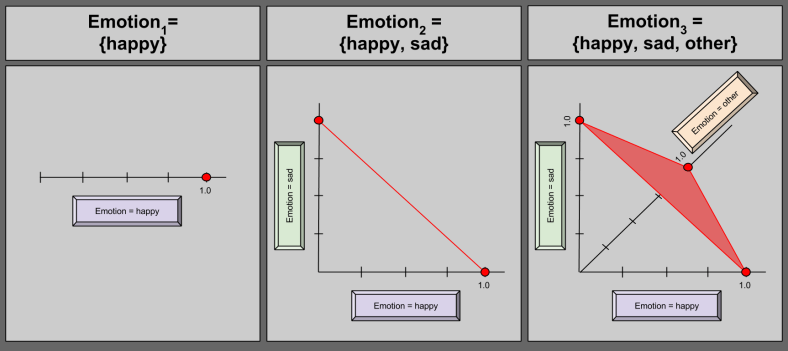

The Machinery Of Possibility

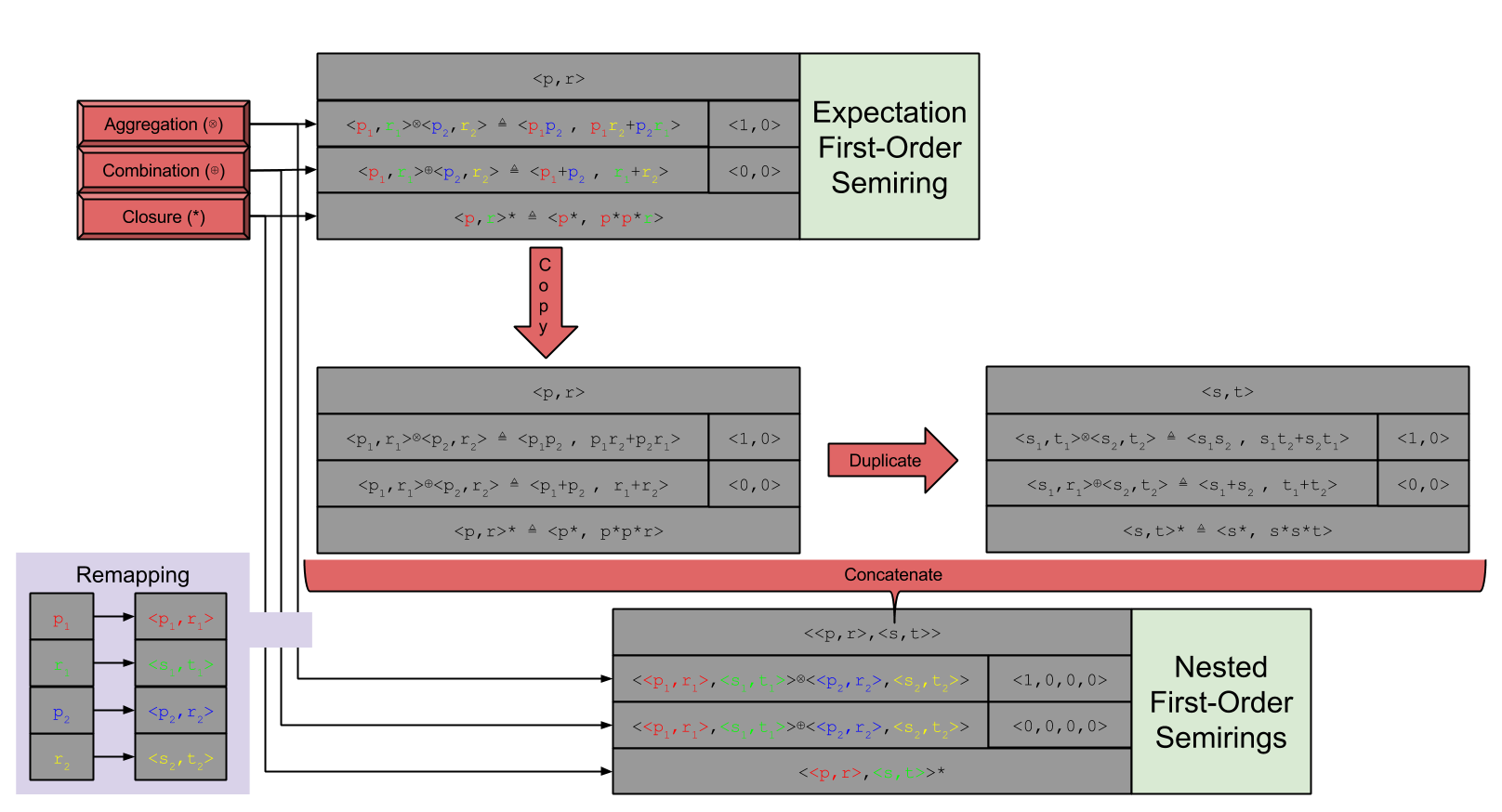

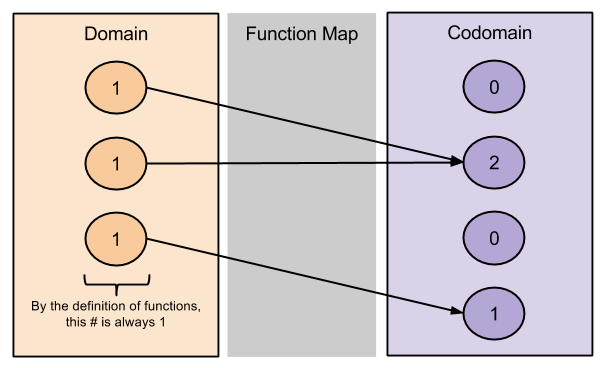

Imagine you are omniscient, and have access to a counterfactual table of possible outcomes. That is, for either possible world (the one where you hand me a drug, and the one where you hand me a placebo), you know whether I beat my cancer. You can then generate predictions as follows:

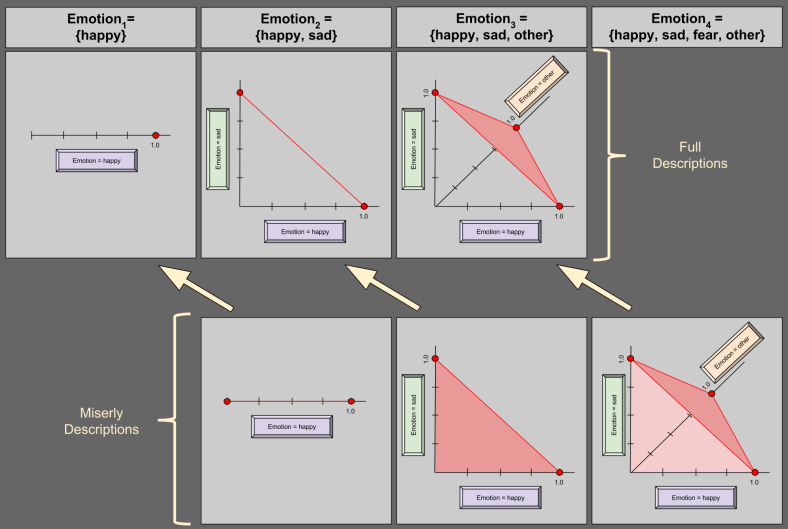

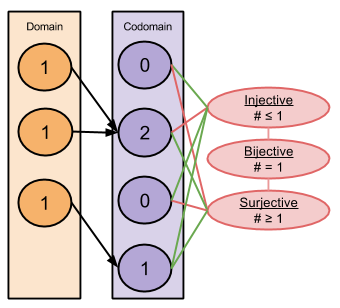

The left table is one of counterfactuals, the right is composed of observables. The X column represents a selector; it selects which column of the counterfactual table from which to draw the value of Y (X=1 means right column, X=0 means left). Pay attention to the color red, until the above makes sense.

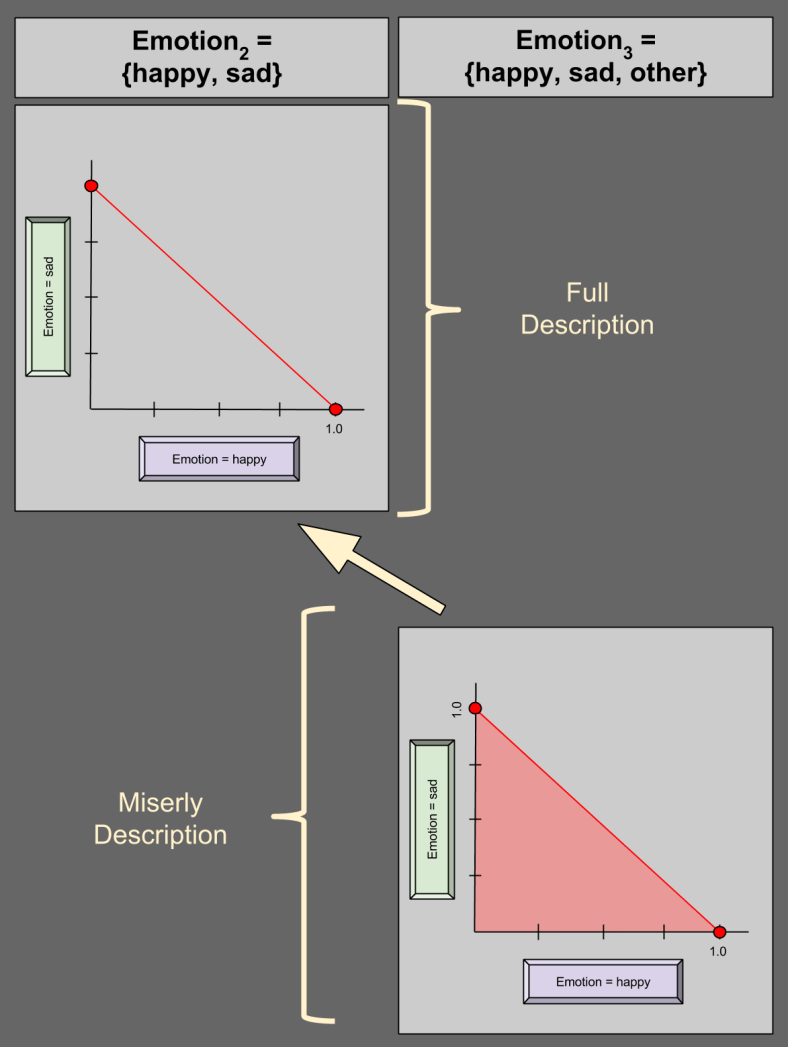

Now let’s relax the problem and admit that we are not omniscient: scientists simply do not possess privileged access to the multiverse. Rather, you simply observe outcomes of individuals. In this world, inference moves from right-to-left, and half of all counterfactual entries are left indeterminate.

As you can see, these indeterminate counterfactuals on the left means that the patient of that row is of indeterminate type. If a patient dies after using the placebo (second row), we do not know whether she would Never Recover, or if she would have been Helped by the drug!

Mechanized Outcome Constraint

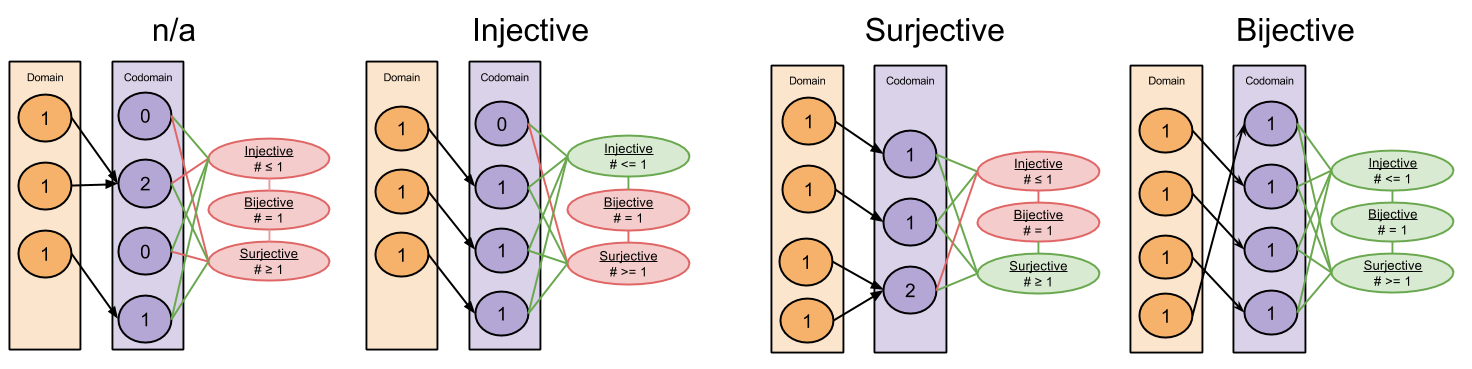

Pay attention to the color patterns in the above image. Could you have predicted that particular pattern? I couldn’t; they feel mysterious.

If you notice your confusion, you are more likely to expend effort to dissolve it. Patterns emerge after the following process:

Please take a minute to come to terms with the above diagram. Do you see how each step flows from the previous? If not, please comment!

After the final step, we notice a nice symmetry between counterfactual results.

Takeaways

- Questions of causality have interesting links to “what if” questions (counterfactuals)

- We can construct a Possible Outcomes model that deploys counterfactual reasoning to explain observed effects

- If we reverse the direction of a Possible Outcomes model, we see that observed reality only partially determines our counterfactual knowledge.

- If we look carefully at the relationship between observed variables and their counterfactual implications, we can begin to see a pattern.

Next time, we will exploit the symmetry above to complete our picture of potential-outcome causality. See you then!