Part of: Reinforcement Learning sequence

Related to: An Introduction to Linear Algebra

Content Summary: 700 words, 7 min read

Motivation

We begin with an example.

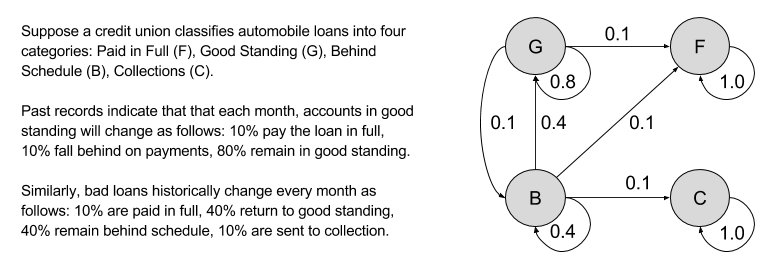

Suppose a credit union classifies automobile loans into four categories: Paid in Full (F), Good Standing (G), Behind Schedule (B), Collections (C).

Past records indicate that each month, accounts in good standing change as follows: 10% pay the loan in full, 10% fall behind on payments, 80% remain in good standing.

Similarly, bad loans historically change every month as follows: 10% are paid in full, 40% return to good standing, 40% remain behind schedule, 10% are sent to collection.

A Markov Chain allows us to express such situations graphically:

Loan statuses are nodes, transition probabilities are arrows.

Markov Property

Formally, a Markov Chain is a tuple (S, P)

- A set of states s ∈ S

- A transition model P(s’ | s).

At the core of Markov Chains is the Markov Property, which states (for time t = n):

This is a statement of conditional independence. If I tell you the history of all prior states, and ask you to predict the next time step, you can forget everything except the present state. Informally, a complete description of the present screens off any influence of the past. Thus, the Markov Property ensures a kind of “forgetful” system.

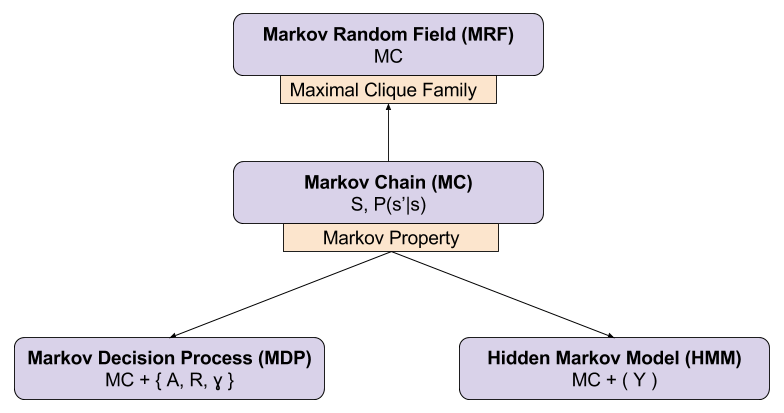

Any model which relies on the Markov Property is a Markov Model. Markov models represent an important pillar in the field of artificial intelligence. Three extensions of Markov Chains are particularly important:

State Expectations by Unweaving

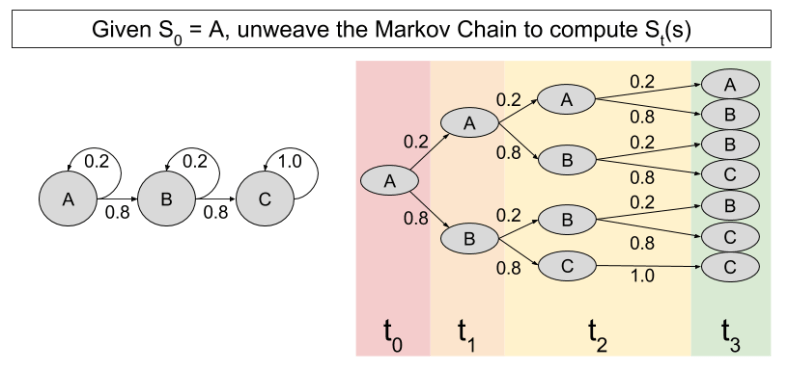

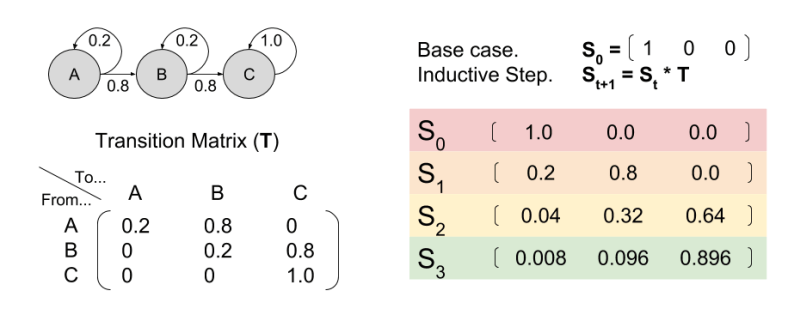

Let’s imagine a Markov Chain with three states: A, B, and C. If you begin at A, where should you expect to reside in the future?

An intuitive way to approach this question is to”unweave” the Markov Chain, as follows:

Each branch in this tree represents a possible world. For example, at t1 there is a 20% chance the state will be A, and an 80% chance the state will be B. Computing expected locations for subsequent timesteps becomes straightforward enough. At t2, we see that:

- There is an (0.2)(0.2) = 4% chance of residing in A.

- There is an (0.8)(0.2) + (0.2)(0.8) = 32% chance of residing in B.

- There is an (0.8)(0.8) = 64% chance of residing in C.

The above computations can be expressed with a simple formula:

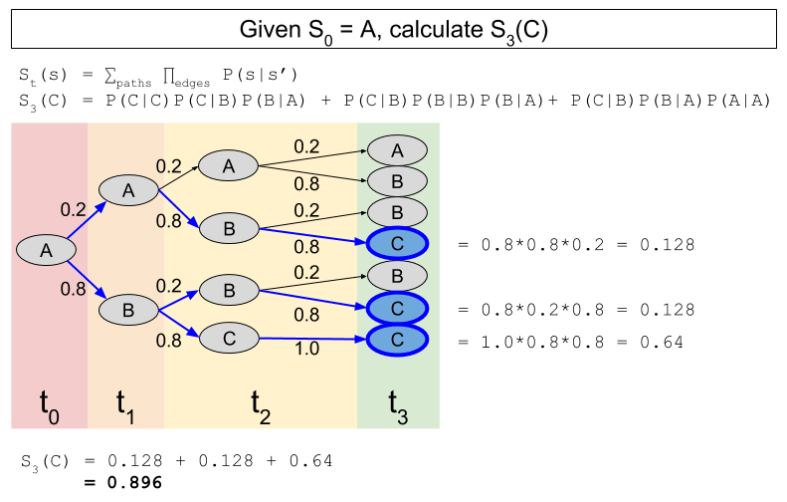

However, these computations become tedious rather quickly. Consider, for example S3(C):

State Expectations By Linear Algebra

Is there a way to simplify the maths of expectation?

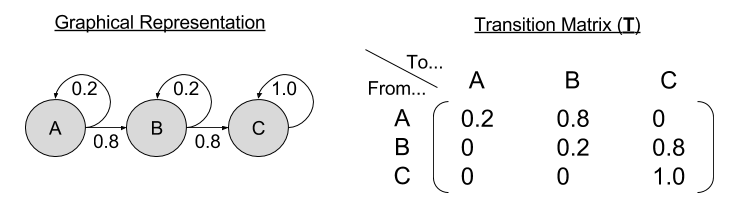

Yes, by approaching Markov Chains through the lens of linear algebra. Conditional probabilities are encoded as transition matrices, as follows:

This representation enables computation of expected location by matrix multiplication:

We compute expectation timesteps sequentially. By defining a base case and an inductive step, this process qualifies as mathematical induction.

As you can see, these maths are equivalent: S3(C) = 0.896 in both cases.

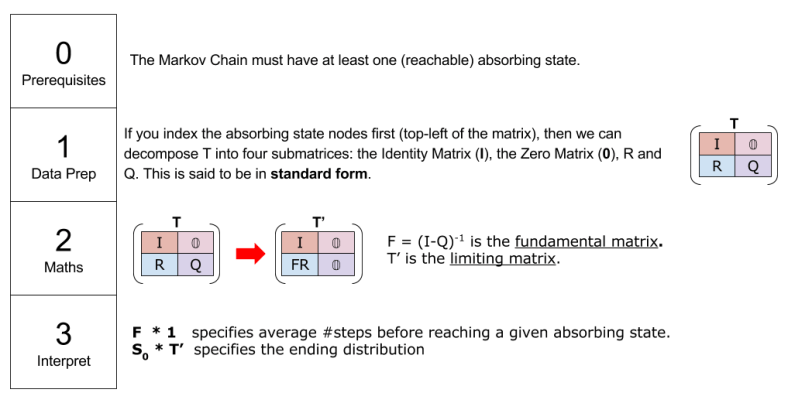

Steady-State Analysis

In the above example, C is called an absorbing state. As time goes to infinity, the agent becomes increasingly likely to reside in state C. That is, Sn = [0 0 1] as n→∞. This finding generalizes. Every Markov Chain that contains a (reachable) absorbing state converges on a distribution in the limit, or limiting distribution.

Can we discover the limiting distribution?

Yes, with the following recipe. First, convert the transition matrix into standard form. Second, apply matrix multiplication and inversion to derive the fundamental and limiting matrix. Last, use these matrices to answer real-world questions about our data:

Let me illustrative with our automotive loan example. First, we prepare our data.

With T in standard form, we compute F = (I – Q)-1 and T’.

Now that we know F and T’, we are in a position to answer questions with our data.

Thus, we are able to predict how Markov Chains will behave over the long run.

Takeaways

- Markov Chains are convenient ways of expressing conditional probabilities graphically

- But they require the Markov Property, that knowledge the present screens off any influence of the past.

- We can compute expected locations by reasoning graphically.

- However, it is simpler to compute expected locations by linear algebra techniques.

- Linear algebra also enables us to discover what (some) Markov chains will approach, their limiting distribution.

Further Resources