Part Of: [Breakdown of Will] sequence

Followup To: [Iterated Schizophrenic’s Dilemma]

This post is addressed to those of you who view personal rules as a Good Thing. If your only thought about willpower is “I wish I had more”, pay attention.

The Breath Of Science

What is human nature?

Suppose that I sat you in a room for fifteen minutes, and had you list as many distinctly human characteristics as you could. How long is your list?

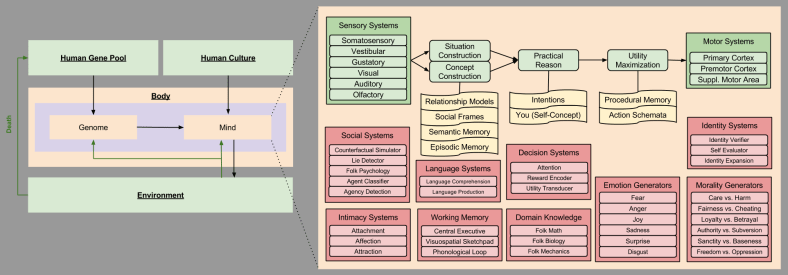

Here’s a first stab at it:

Observation is the breath of science. But what’s next?

Most people don’t know how to think scientifically. This skill can only be learned by doing, but let me gesture at the tradecraft in passing.

The first step: give your observations names. A name is the sound you brain makes while hitting CTRL-S.

Observations are not bald facts. Observations cry out for explanation (they are explananda).

Science is in the business of building prediction machines (also known as explanations, or theories).

Theory builders keep an implicit picture of their target explananda. The mechanization of science will bring with it explananda databases.

Those who forbids nothing live in ignorance. The secret of knowledge is expectation constraint.

The scientific lens, then, interprets observation as explanation-magnets. Theories explain observations indirectly, by painting the space of impossibility.

The mind of a scientist flows in this direction: bald observation → named patterns → explananda → prediction machine → theory integration.

A Tale Of Four Side-Effects

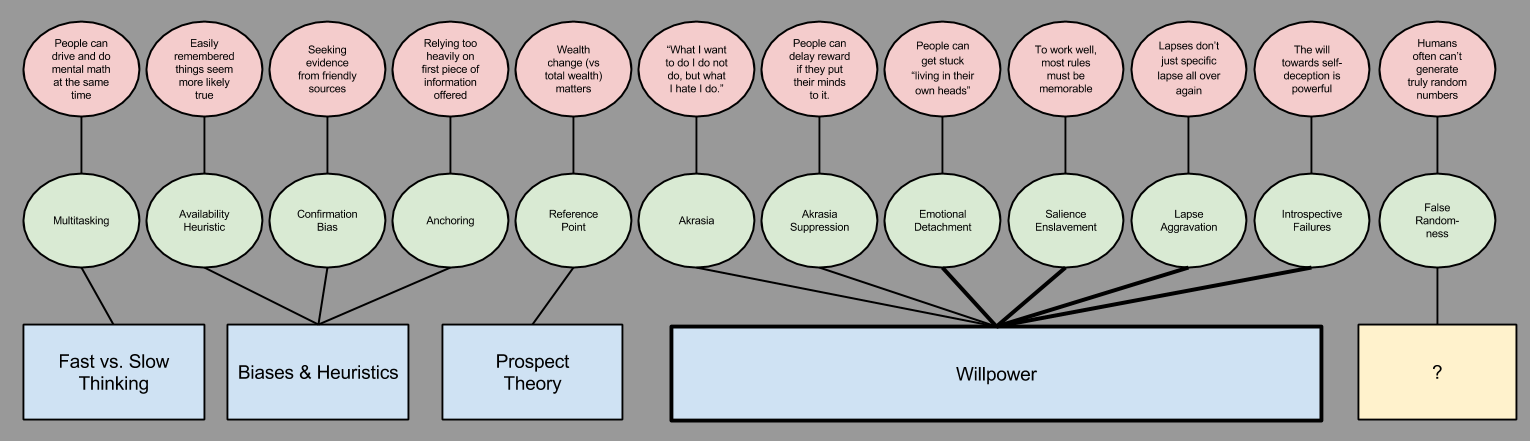

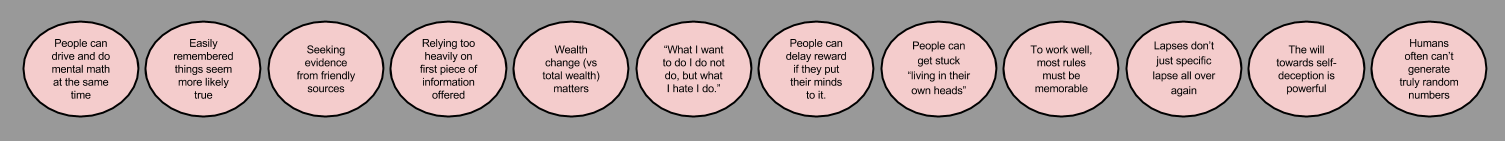

The above list features five explananda divorced from theory. This is, of course, to be expected.

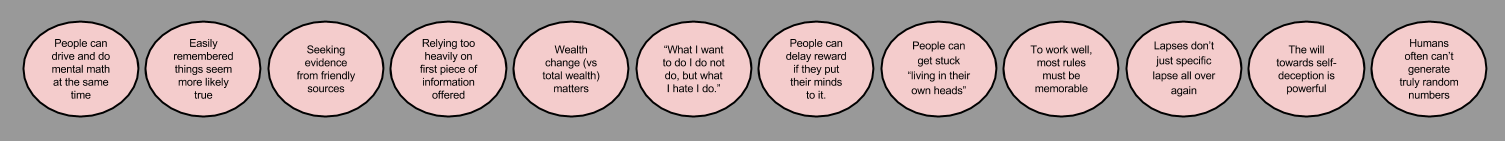

Here are the first four observations. At first glance, these may not seem particularly related.

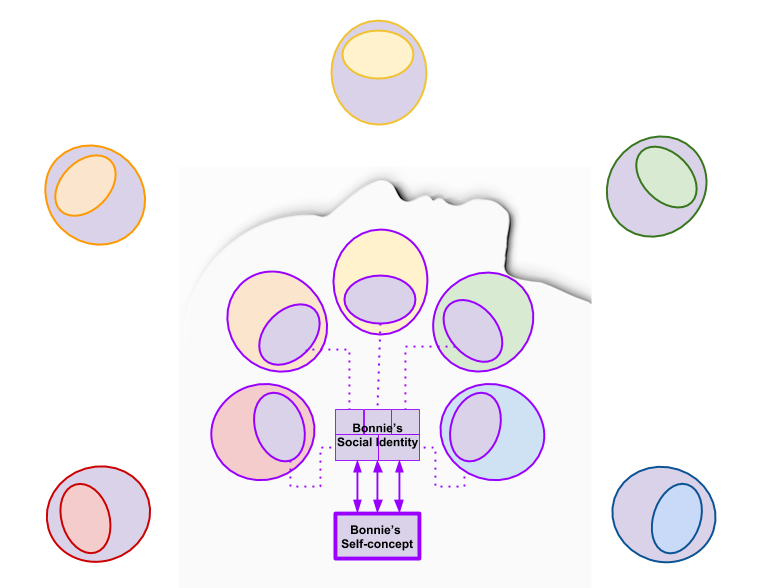

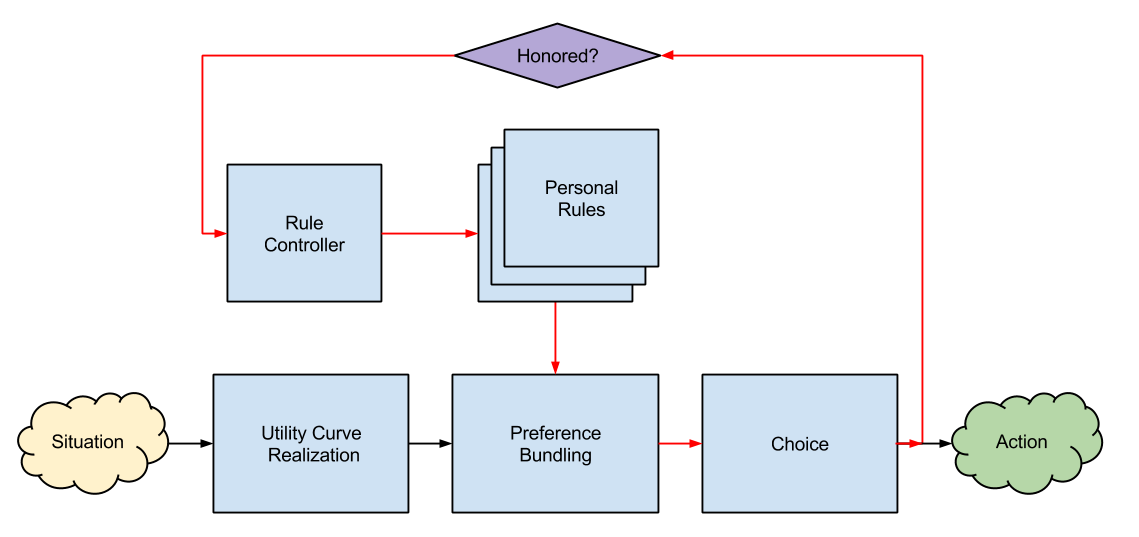

- Modernity tends to suffer from people “living in their own heads”, unable to appreciate the subtleties of experience. Call this emotional detachment.

- Rules tend to be all-or-nothing, erring on the side of memorability above reasonableness. Call this salience enslavement.

- When people fail to meet some standard, that failure tends to repeat itself more than other failures. Call this lapse aggravation.

- People are prone to self-deception. Call such events introspective failures.

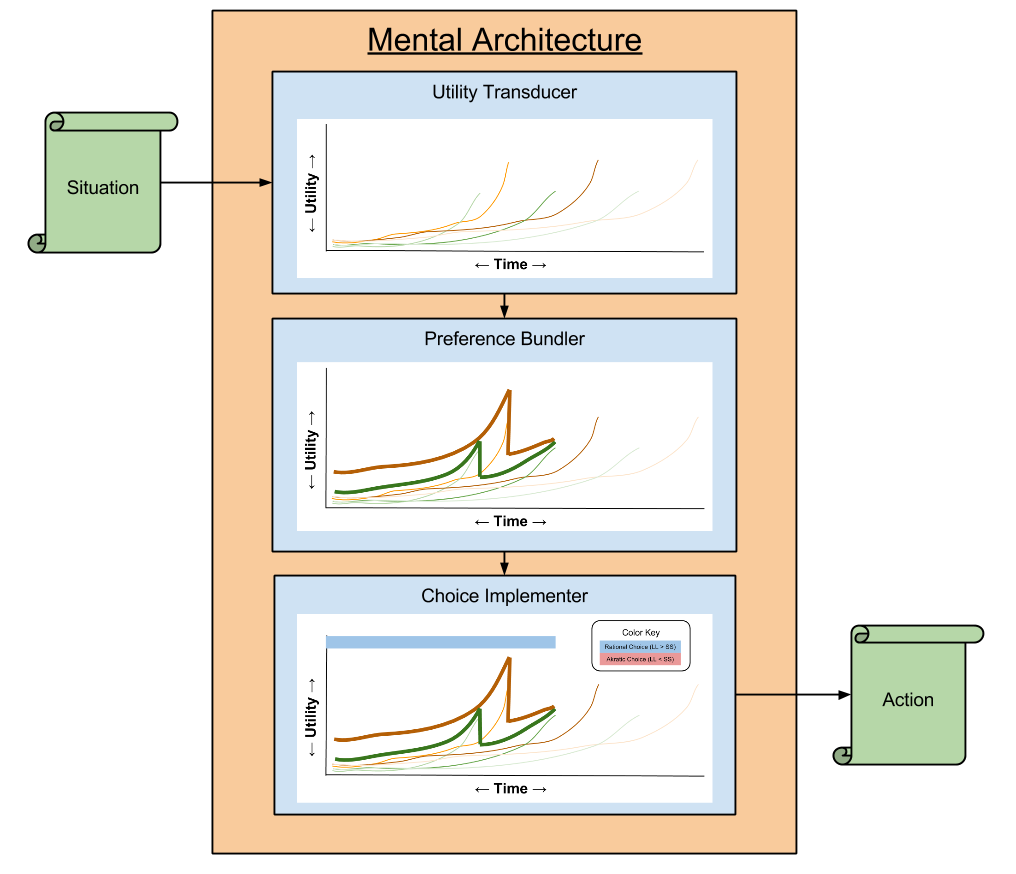

By now, I have completed my sketch of Ainslie’s theory of willpower (willpower is preference bundling, implemented as personal rules). One reason to take this theory seriously, is that it explains why humans suffer from these syndromes. The surprising nature of these connections is a virtue in science.

All of this is not to say that willpower is undesirable. Willpower is just not unequivocally beneficial. If you are in the business of authoring rules for yourself, you would be well-advised to account for the risks.

Let me now turn to how our theory of willpower entails these four uncomfortable “side effects”.

On Emotional Detachment

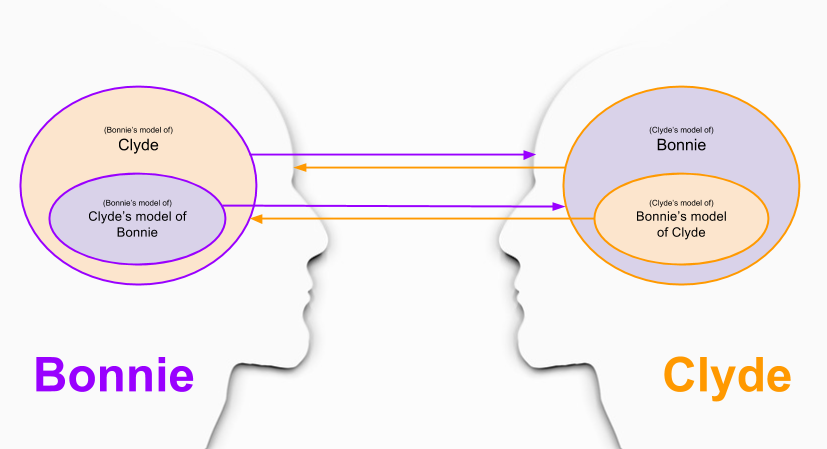

Let’s return to a central result of the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma (IPD). Recall that IPD has both prisoners repeatedly tempted to “rat” on one another for a wide range of different charges, with no end in sight. Suppose the DA has 40 separate questions for which they will give less prison time to the prisoner who provides information. Is it in the government’s interest to tell the prisoner’s how long they will be playing this game?

The answer is yes! On round 40, each prisoner will know that they will have nothing to lose by trusting one another, and defect. On round 39, each prisoner will anticipate the other to betray them on round 40, so they can’t do better than defecting on that previous round too. This chain of reasoning threatens to contaminate the entire iterated game. Prisoners will be more likely to cooperate with one another if the length of their game is let unknown.

Can known-termination collapse apply to games played between your interpersonal selves? Not only does it apply, but I know of no better explanation for the change that strikes many people when they are told they have X months to live. Consider the story of Stephen Hawking. When he was diagnosed at twenty-one years old, he was given two years to live. Fortunately, the diagnosis was inaccurate, but Stephen credits his diagnosis with adding urgency to his work, inspiring him to “seize the moment” before it was too late.

Why should personal rules run at odds with living in the moment?

Attention is a finite resource. When you spend it analyzing situations for rule-conformance, your choices become detached from the here-and-now. Perhaps this is the birthplace of loss of authenticity, that existential philosophers complain of in modern society generally.

On Salience Enslavement

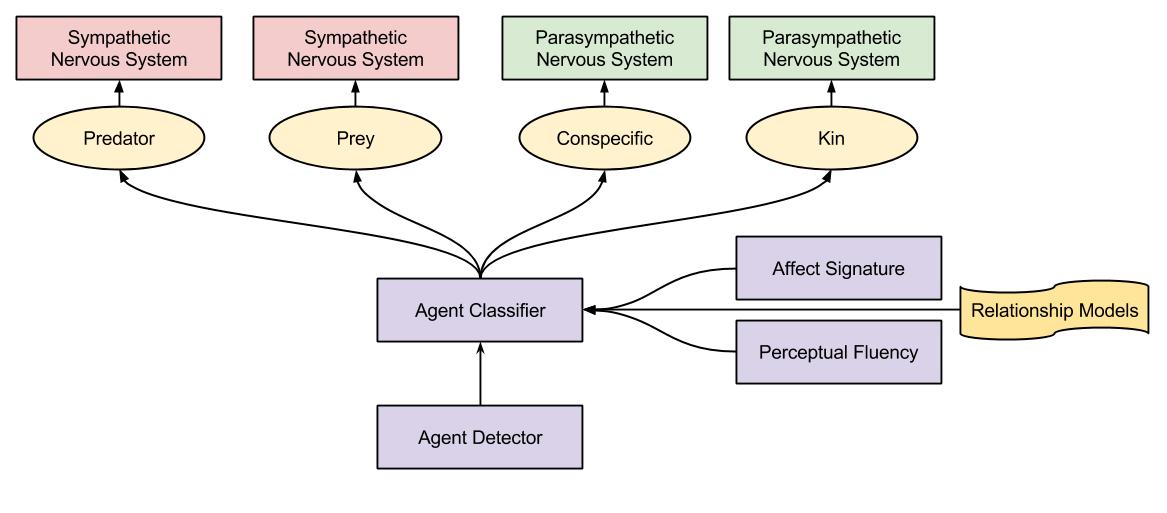

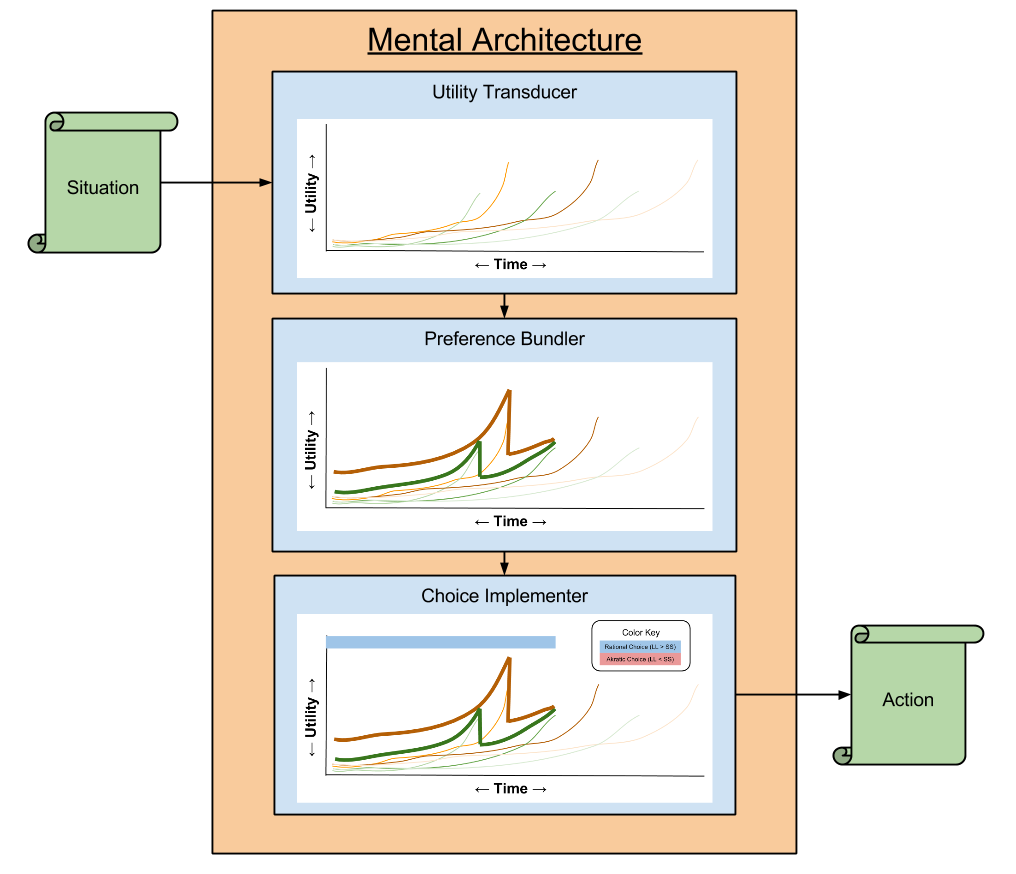

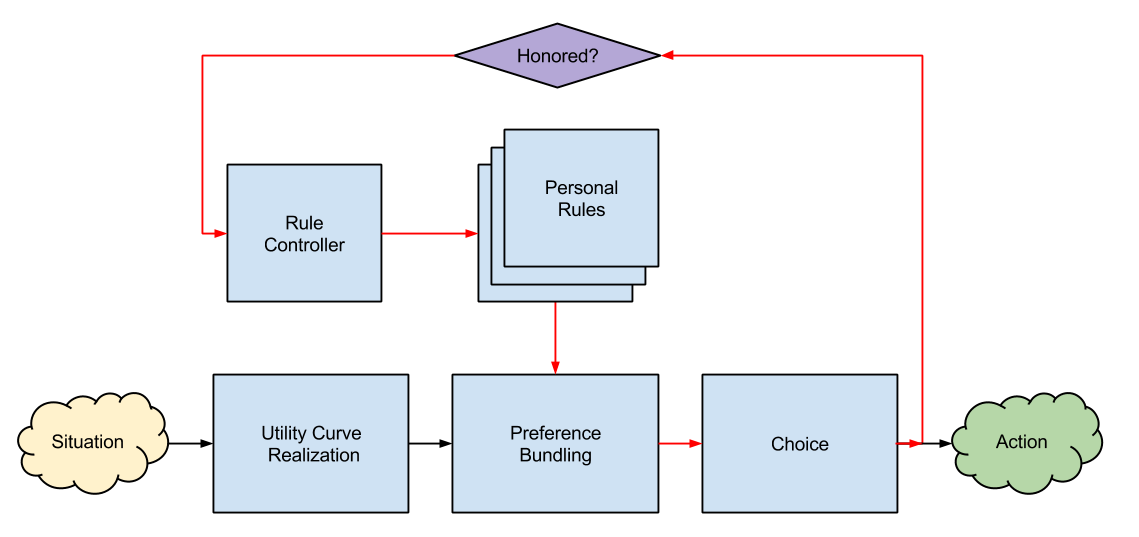

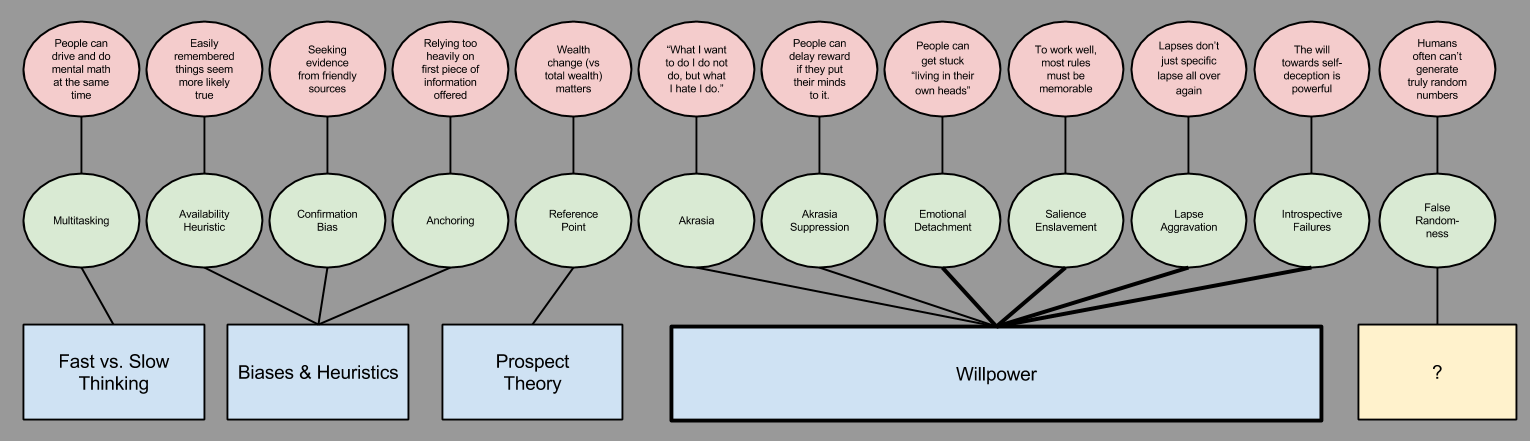

If neuroeconomics has taught us anything, it is that decision-making is an algorithm. But consider the effect of injecting a Preference Bundler inside of such an algorithm:

Preferences are bundled according to personal rules. However, our memory systems deliver these rules in differing degrees of strength.

Personal rules operate most effectively on memorable goals. Let’s imagine for a moment that it is medically beneficial to consume half a glass of wine a night. Consider the case of a non-alcoholic who nevertheless, consumes a medically unwise amount of alcohol. Would you advise him adopt a rule of half a glass, or no alcohol at all?

While the absolute difference between a half-glass and no wine is small, the memorability of either differs dramatically. You can observe the same effect in three chocolate chips vs. no chocolate chips, or one white lie vs. total honesty.

But memorability (salience) is not always so innocent. The exacting personal rules of anorectics or misers are ultimately too strict to promise the greatest satisfaction in the long run, but their exactness makes them more enforceable than subtler rules that depend on judgment calls. In general, the mechanics of policing this cooperation may increase your efficiency at reward getting in the categories you have defined, but reduce your sensitivity to less well-marked kinds of rewards.

On Lapse Aggravation

In Epistemic Topography, I discuss the notion of identity bootstrapping:

I pursue deep questions because I tell myself I am curious → I tell myself I am curious because I pursue deep questions.

Personal rules share an analogous pattern of commitment bootstrapping:

If I renege on my commitment, I am unlikely to do the right thing next time → If I can’t count on my future self, it’s best to take things into my own hands now.

Both phenomena constitute positive feedback:

Have you ever heard a microphone squeal because it gets too close to the speakers? This is another artifact of positive feedback:

If a microphone detects noise (e.g., a singer) then the speakers will amplify it → if the speakers produce noise the microphone may detect it

The squeal of the microphone that makes you wince is literally the loudest sound a speaker can produce without blowing a fuse. This effect is not unique to acoustics: all systems that rely on positive feedback are both powerful and unstable.

Suppose I were to build a strong interpersonal rule against eating cheese, but then I lapse. Without the rule, such a decision would be have no bearing on my sense of identity. However, with the personal rule in place, I have just sent myself evidence of non-compliance, my present-self loses confidence that my future-self will sustain my best interests.

Consider the stories you have encountered of children raised in a very strict atmosphere, who have since matured and rebelled. Surely you can think of a time when the rebellion is not simply to adopt a new identity, but instead fall towards an anti-identity. Malignant failure modes owe their roots to the fabric of rules themselves.

On Introspective Failures

Consider again our poor compatriot who has just lapsed in violation of her personal anti-cheese commitment. This person’s short-range interest is in concealing the lapse, to prevent detection so as not invite attempts to throw out the cheese. What’s more, the person’s long-range interest is in a similarly awkward position where admitting defeat risks birthing a new malignant failure mode.

The individual’s long-term interests is in the awkward position of a country that has threatened to go to war under some scenario. The country wants to avoid war without destroying the credibility of its threats, and may therefore look for ways to be seen as not having detected the circumstance.

Willpower thus creates perverse incentives. These incentives explain how money disappears despite a strict budget, or how people who “eat like a bird” mysteriously gain weight. To preserve the right to make promises to oneself, we fallen victim to self-deception.

Takeaways

This post is addressed to those of you who view personal rules as a Good Thing. If your only thought about willpower is “I wish I had more”, pay attention.

Willpower is not an unmixed blessing. If willpower is preference bundling, implemented as personal rules, then willpower brings with it four uncomfortable side effects:

- Emotional detachment: Attending to personal rules tends to induce the “living in your own heads” (an inability to appreciate the subtleties of experience).

- Salience enslavement: Personal rules tend to be all-or-nothing, erring on the side of memorability even at the cost of reasonableness.

- Lapse aggravation: Personal rules are powerful feedback loops. When rules are followed they get stronger, but lapses not only occur but also promote failure modes.

- Introspective failures: Decisions are made in the context of interpersonal warfare. On the event of a lapse, both of your selves are incentivized towards self-deception.

All of this is not to say that willpower is undesirable. Willpower is simply not unequivocally beneficial. If you are in the business of authoring rules for yourself, it pays to be informed of the risks.