Part Of: [Advanced Inference In Graphical Models] sequence

Table Of Contents

- Introduction

- Article Metadata

- Item-Based Description

- Candidate Semirings

- Mechanizing Algorithm Construction

- Algorithm-Metaring Diplomacy

- Conclusion

Introduction

There are 1,024 logical permutations of rings/fields. Why is so much of the algorithmic research on them focused on one particular class of algebraic structure: the semiring? Why not the ring, or the pseudoring?

One answer can be made by appealing to historical accident. Semiring-based algorithm generation methods were championed most prominently by the Natural Language Processing (NLP) community, because the Chomsky–Schützenberger theorem unearthed deep connections between context-free grammars and certain noncommutative semiring algebras.

This post is a summary of John Goodman’s article, Semiring Parsing, which applies group theoretic techniques to already-known algorithms used by NLP researchers.

Article Metadata

- Article: Semiring Parsing

- Author: John Goodman

- Published: 1999

- Citations: 126 (note: as of 11/2014)

- Link: Here (note: not a permalink)

Item-Based Description

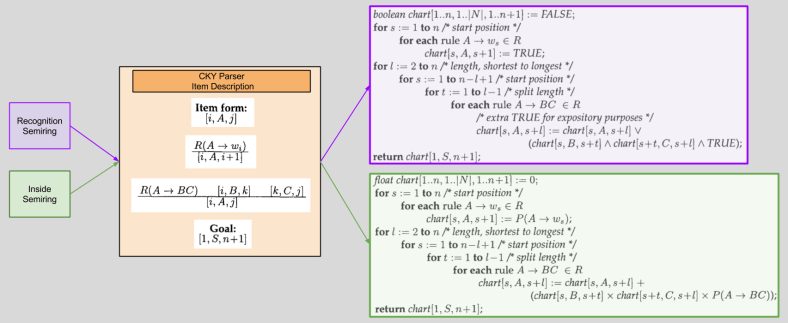

One major innovation in Goodman’s paper is item based descriptions. The syntax is straightforward:

This kind of notation simplifies the specification of parsers. More generally, as we will see, it will also free us from the traditional procedural-based approach to constructing algorithms in this domain.

Semiring Types

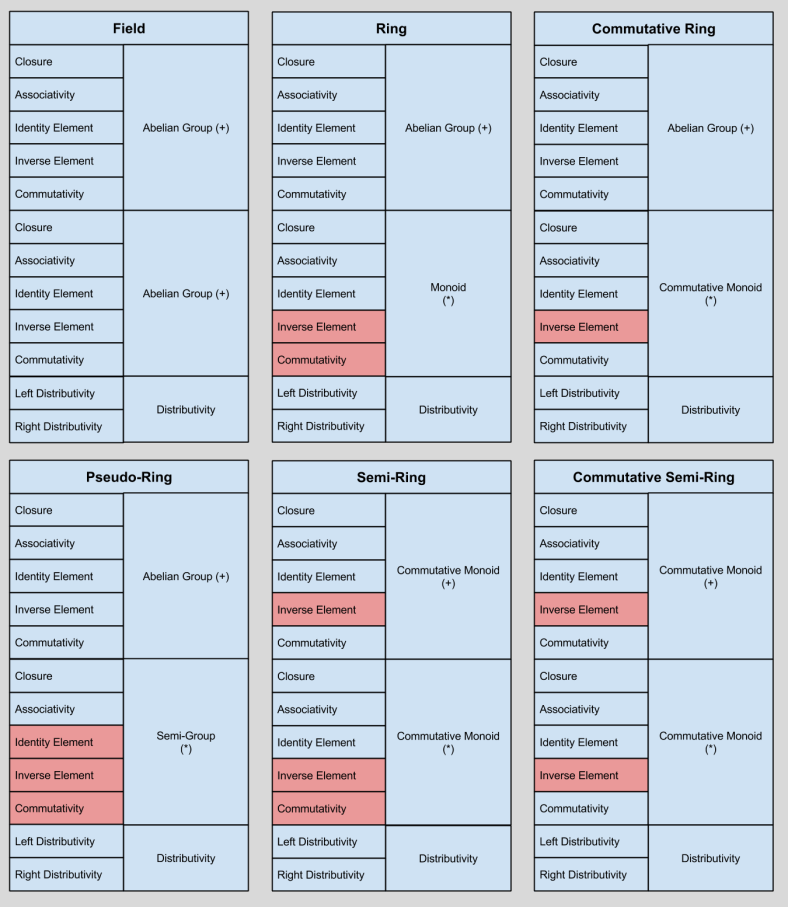

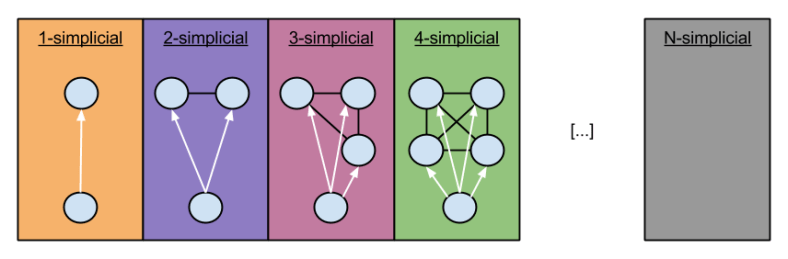

Let me call any type of permutation within a group-like structure a metagroup, and let me call any type of permutation within a ring-/field- like structure a metaring.

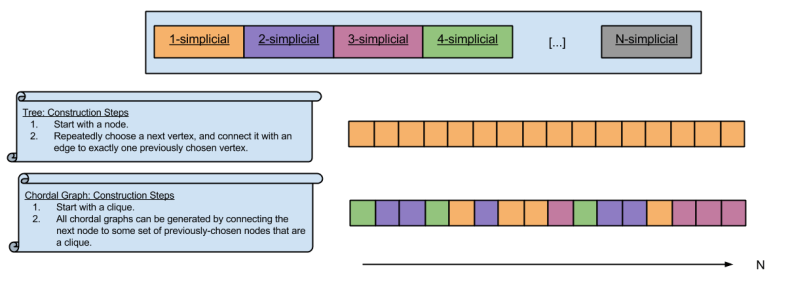

Another bit of background: do you remember the space of metarings? Here’s a diagram to refresh your memory:

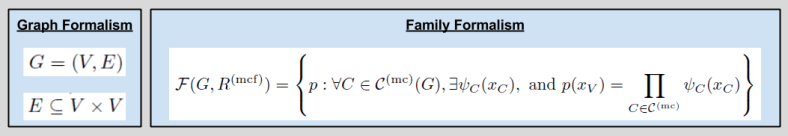

Ring-like algebraic structures only have five differentiating factors: the input set over which they operator, the aggregation operator, the combination operator, and their two identity elements.

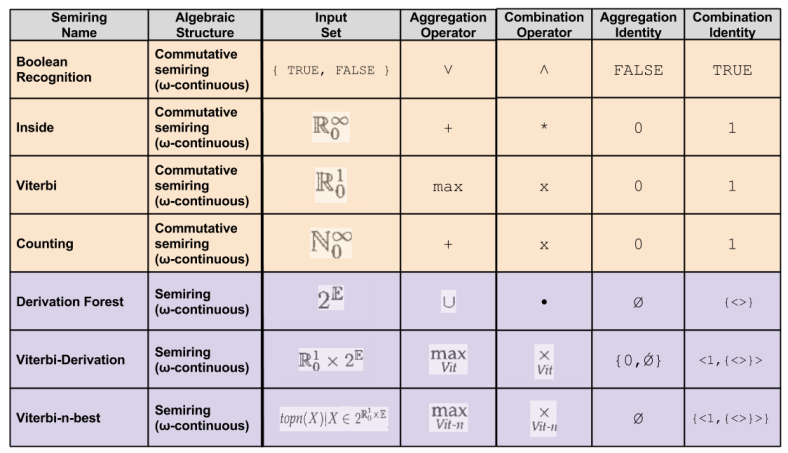

We can imagine a multitude of different permutations of these five variables. In the NLP community, seven permutations stand out as particularly valuable. They are:

Mechanizing Algorithm Construction

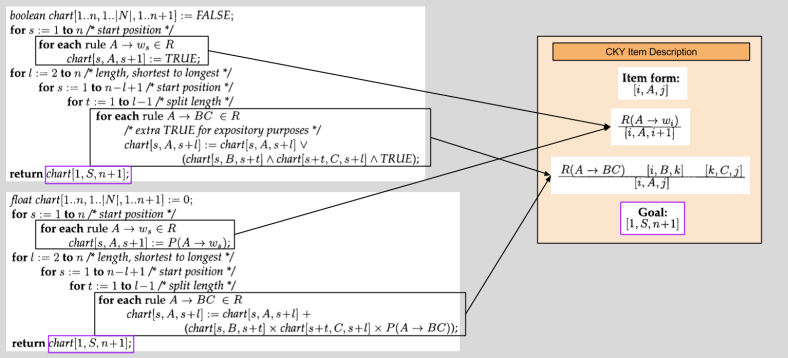

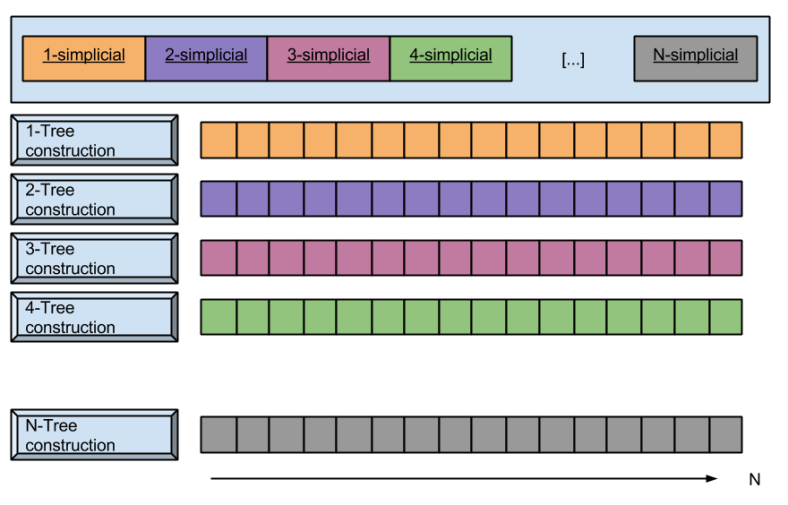

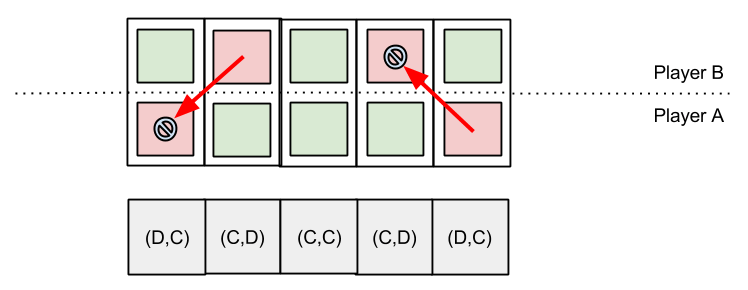

Consider the following algorithms:

Notice any similarities?

You should! The only differences between the two algorithms are substitutions between:

- ˄ <–> *

- ˅ <–> +

- P(*) <–> TRUE

Let’s leverage item descriptions to generalize these two algorithms:

With our new Item Description, algorithm generation becomes mechanized:

What makes this plug-and-play system more compelling than merely an ad-hoc explanation of algorithms whose existence we have already described?

Well, the Item Description doesn’t just accept these two semirings! Plug more in, and see what you get. 🙂 As Goodman puts it:

It [now becomes] easier to generalize parsers across tasks: a single item-based description can be used to compute values for a variety of applications, simply by changing semirings.

Algorithm – Metaring Diplomacy

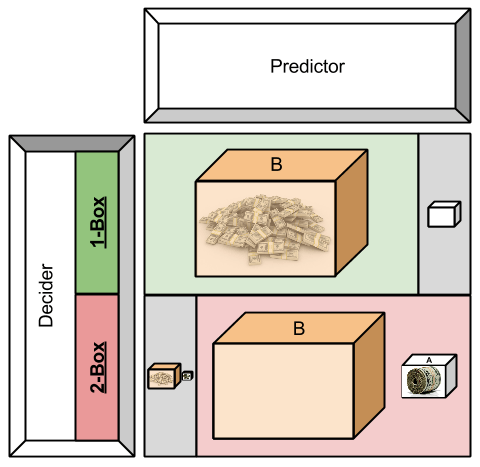

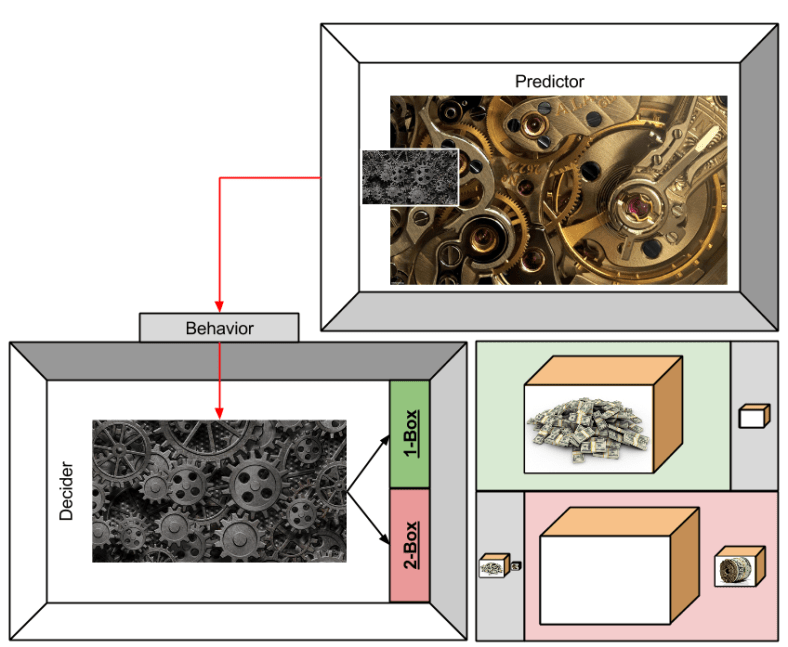

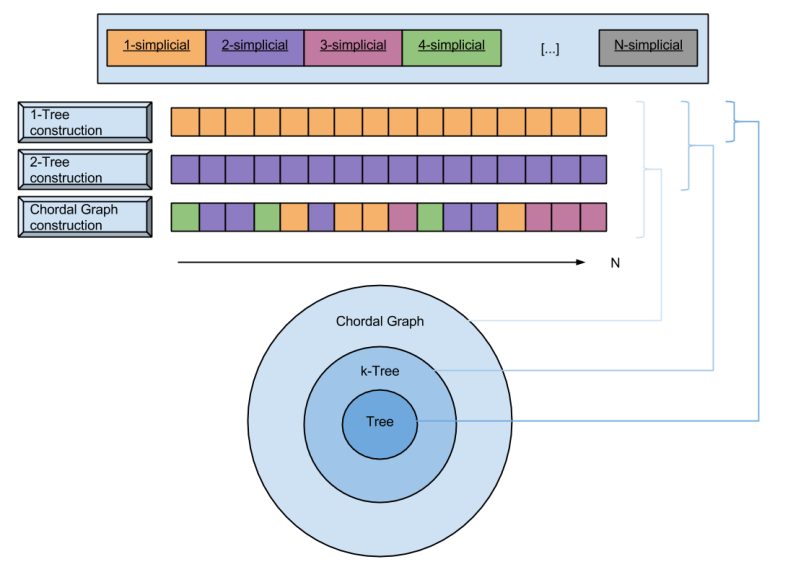

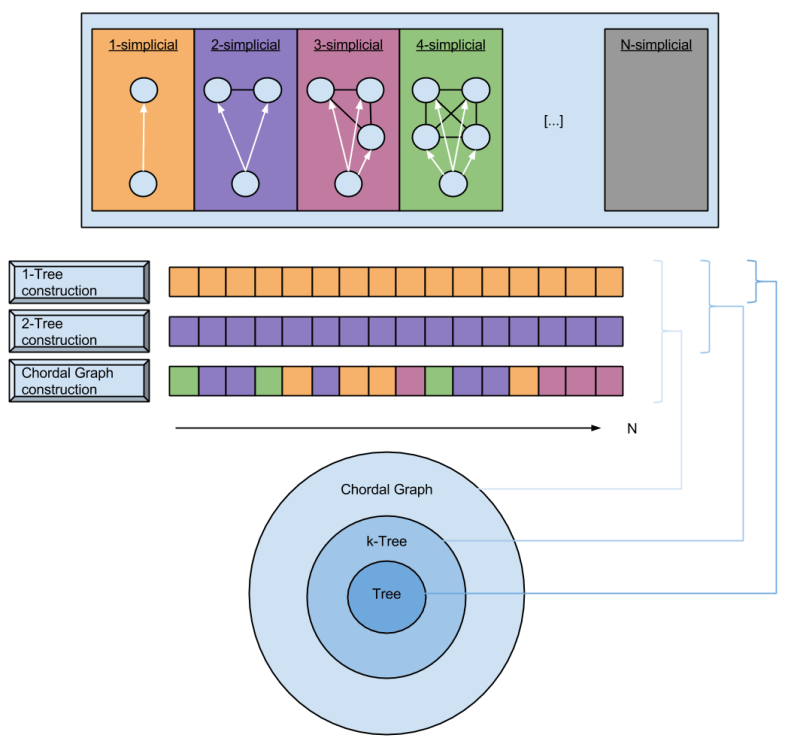

Algorithms are often designed so that they can accept particular algebraic structures.

In typical practical Viterbi parsers, when two derivations have the same value, one of the derivations is arbitrarily chosen. In practice, this is usually a fine solution… but from a theoretical viewpoint, the arbitrary choice destroys the associative property of the additive operator, max. To preserve associativity, we keep derivation forests of all elements that tie for best.

Computing over infinite sets is one powerful reason why commutivity is a desideratum for these metarings:

For parsers with loops, i.e., those in which an item can be used to derive itself, we will also require that sums of an infinite number of elements be well defined. In particular, we will require that the semirings be complete. This means that sums of an infinite number of elements should be associative and commutative, just like finite sums, and that multiplication should distribute over infinite sums, just as it does over finite ones.

Commutativity is shed in the three derivation-based semirings, for the simple reason that its multiplicative operator is designed to be order-preserving:

These semirings, unlike the other semirings described in Figure 5, are not commutative under their multiplicative operator, concatenation.

Swapping out semirings is not the only strategy to exploring parser diversity. One can also swap out the sets within the Item Descriptions.

Notice that each of the derivation semirings can also be used to create transducers. That is, we simply associate strings rather than grammar rules with each rule value. Instead of grammar rule concatenation, we perform string concatenation. The derivation semiring then corresponds to nondeterministic tranductions; the Viterbi semiring corresponds to a probabilistic transducer; and the Viterbi-n-best semiring could be used to get n-best lists from probabilistic transducers.

Think only two operators are allowed in a metaring? Think again!

Notice that [in the above example] we have multiplied an element of the semiring, V(D), by an integer, C(D, x). This multiplication is meantto indicate repeated addition, using the additive operator of the semiring. Thus, for instance, in the Viterbi semiring (max-product), “multiplying” (repeat-“addition”) by a count other than 0 has no effect, since x “+” x = max(x, x) = x. Whereas in the inside semiring (sum-product), repeat-“addition” corresponds to actual multiplication.

An interesting connection between finite-state automata and HMMs:

Nondeterministic finite-state automata (NFAs) and HMMs turn out to be examples of the same underlying formalism, whose values are simply computed in different semirings. Other semirings lead to other interesting values… For NFAs, we can use the boolean semiring to determine whether a string is in the language of an NFA; we can use the counting semiring to determine how many state sequences there are in the NFA for a given string; and we can use the derivation forest semiring to get a compact representation of all state sequences in an NFA for an input string. A single item-based description can be used to find all of these values.

Goodman in his paper calls for an extension of item-based descriptions:

It would be interesting to try to extend item-based descriptions to capture some of the formalisms ocvered by Koller, McAllester, and Pfeffer, including Bayes’ nets.

Conclusion

My Open Questions:

- Have item-based descriptions since been extended? Is there active research on this front?

Concluding Quote:

In summary, the techniques of this paper will make it

- easier to compute outside values,

- easier to construct parsers that work for any ω-continuous semiring, and

- easier to compute infinite sums in those semirings.

In 1973, Teitelbaum wrote:

“We have pointed out the relevance of the theory of algebraic power series in noncommuting variables in order to minimize further piecemeal rediscovery”

We hope that this paper will bring about Teitelbaum’s wish.