Part Of: Anthropogeny sequence

See Also: Born to Run: a theory of human anatomy

Content Summary: 2100 words, 21 min read

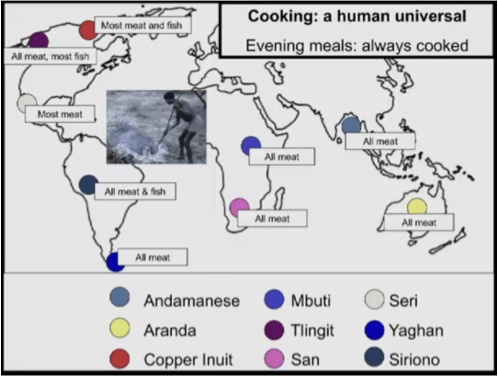

The Universality of Cooking

Cooking is a human universal. It has been practiced in every known human society. Rumors to the contrary have never been substantiated. Not only is the existence of cooked foods universal, but most cuisines feature cooked foods as the dominant source of nutrition.

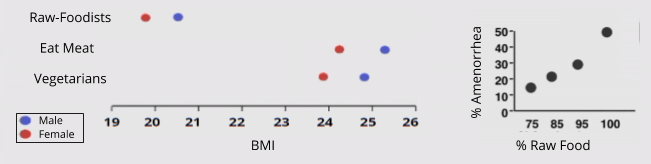

Raw foodists comprise a community dedicated to consuming uncooked food. Of course, compared to historical hunter-gatherers, modern raw foodists enjoy a wide variety of advantages. These include:

- Elaborate food preparation (pounding, purees, gently warming),

- Elimination of seasonal shortages (supermarkets)

- Genetically enhanced vegetables with more sugar content and fewer toxins.

Despite these advantages, raw foodists report significant weight loss (much more than vegetarians!). Further, raw foodists suffer from increasingly severe reproductive impairments, which have been linked to not getting enough energy.

Low BMI and impaired reproduction are perhaps manageable in modern times, but are simply unacceptable to hunter-gatherers living at subsistence levels.

The implication is clear: there is something odd about us. We are not like other animals. In most circumstances, we need cooked food.

The Energetics of Cooking

Life exists to find energy in order to make more copies of itself. Feeding and reproduction are the twin genetic imperatives.

Preferences are subject to natural selection. The fact that we enjoy cooked food suggests that cooking provides an energy boost to its recipients. The raw-foodist evidence hints towards this conclusion as well. But there is also direct evidence in rats that cooking increases energy gains.

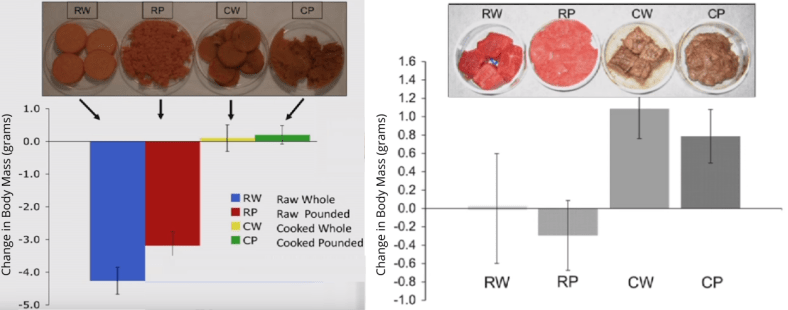

In the following experiments, rat food was either processed/pounded, cooked, neither, or both. After giving this diet over the course of four days, rats in each condition were weighed.

For starches (left) and meat (right), cooking is by far more effective at preventing weight loss and promoting weight gain. Tenderizing food can sometimes help, but that technique pales in comparison to cooking.

The above results were taken from rats. But similar results have replicated in calves, lambs, piglets, cows, and even salmon. It seems to be universally true that cooking improves the energy derived from digestion, sometimes up to 30%.

How does cooking unlock more energy for digestion?

First, denaturation occurs when the internal bonds of a protein weaken, causing the molecule to open up. Heat predictably denatures (“unfolds”) proteins, and denatured proteins are more digestible because their open structure exposes them to the action of digestive enzymes.

Besides heat, three other techniques promote denaturation: acidity, sodium chloride, and drying. Cooking experts constantly harp on these exact techniques, because it aligns with eating preferences.

Second, tender foods is another boon to digestion, because they offer less resistance to the work of stomach acid. If you take rat food, and inject air into the pellets, that does not augment denaturation. Nevertheless, softening food in this way improves the energy intake of the rat.

Cooking does have negative effects. It can cause a loss of vitamins, and give rise to long-term toxic molecules called Maillard compounds, which are linked to cancer. But from an evolutionary perspective, these downsides are overshadowed by the impact of more calories. In subsistence cultures, better fed mothers have more, happier, and healthier children. When our ancestors first obtained extra calories by cooking their food, they and their descendants past on more genes than others of their species who ate raw.

A Brief Review of Human Evolution

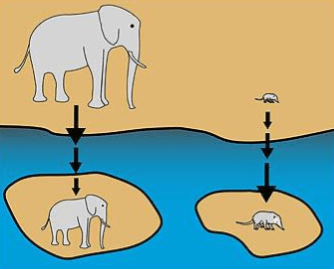

The most recent common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees lived 6 mya (million years ago). But the first three million years of our heritage are not particularly innovative, anatomically. The australopiths were essentially bipedal apes. They could walk comfortably, but retained their adaptations for tree living as well. There is some evidence that australopiths acquired food from a new source: tubers (the underground energy storage system of plants).

Climate change is responsible for the demise of the australopiths. Africa began getting dryer about 3 million years ago, making the woodlands a harsher and less productive place to live. Desertification would have reduced the wetlands where Australopiths found fruits, seeds, and underwater roots. The descendents of Australopithecus had to adapt their diet.

The paranthropes adapted by promoting tubers (underground storage organs of plants) from backup to primary food. In contrast, the habilines (e.g., Homo Habilis) took a different strategy: meat eating. These creatures inherited tool making from the late australopiths (Mode 1 tools, the Oldawan industry- was discovered in Ethiopia 2.6 mya), and used these tools to scrape meat off of bones). The habilines are more ecologically successful, and lead to:

- 1.9 mya: The erects (e.g., Homo erectus/ergastor) with significantly larger brains and near-modern anatomies.

- 0.7 mya: The archaics (e.g., Homo Heidelbergensis) appear, who eventually give rise to the Neanderthals, Denisovans, and us.

- 0.3 mya The moderns (e.g., Homo Sapiens) emerge out of Africa, and completely conquer the globe.

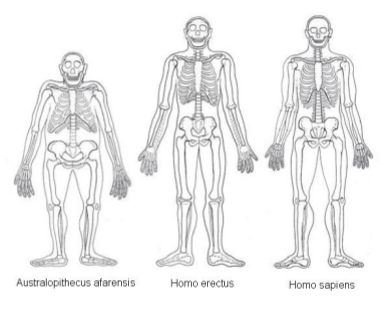

Here is a sketch of how our body plans have changed across evolutionary time:

Explaining Hominization

The transition from habiline to erects deserves a closer look. We know erects evolved to be persistence hunters. But a number of paradoxes shroud their emergence:

- Digestive Apparati. The erect diet appears to be mainly meat and tubers. Both require substantial jaw strength and digestive apparati. Yet the Homo genus features a dramatically reduced digestive apparatus. How was smaller mouths, weaker jaws, smaller teeth, small stomachs, and shorter colons an adaptive response to eating meat and starches?

- Expensive Tissue. Australopiths brain size stayed relatively constant at 400 ccs (10% of resting metabolism). Erect brains began to grow. This transition ultimately yielded a 1400 cc brain (20% of resting metabolism) in archaic humans. How did the erects find the calories to finance this expansion?

- Time Budget. The above anatomical features of erects are geared towards endurance running, which suggests that their lifestyle involved persistence hunting. Chimps have about 20 minute intervals in between searching for & chewing food. Thus, chimps can only afford to spend 20 minutes hunting before giving up. How did erects perform the risky behavior of persistence hunting, which consumes 3-8 hours of time?

- Thermal Vulnerability. As part of their new hunting capabilities, erects became the naked ape (with a new eccrine sweat gland system to prevent overheating). But Homo Erectus also managed to migrate to non-African climates such as Europe. How did these creatures stay warm?

- Predator Safety. Erects lost their anatomical features for arboreal living, which suggests they slept on the ground. Terrestrial sleeping is quite dangerous on the African savannah. How did erects avoid predation & extinction?

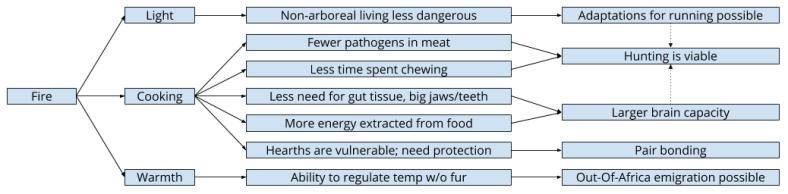

All of these confusing phenomena can be explained if we posit H. erectus discovered the use of fire, and its application in cooking:

- Digestive Apparati. As we have seen, the primary role of cooking is to “externalize digestion”, and to increase the efficiency of our digestive tract. Cooked meat and starches are incredibly less demanding to process than their raw alternatives. This explains our reduced guts. By some estimates, the decrease in digestive tissue corresponds with a 10% energy savings by our erect ancestors.

- Expensive Tissue. Cooking increases the metabolic yield of most foodstuffs by ~30%. For reference, a 5% increase in ripe fruit for chimpanzees reduces interbreeding interval (time between children) by four months. 30% is an absurdly large energy gain, enough to “change the game” for the erects..

- Time Budget. Cooking freed up massive amounts of time otherwise spent chewing. Chimpanzees can take 4-7 hours per day chewing; humans only need one hour per day. This frees up massive amounts of time, which can be used for e.g., hunting.

- Thermal Vulnerability. It is very difficult to explain a hairless Homo Erectus thriving on the colder Asian continent without control of fire.

- Predator Safety. It is very difficult to explain how erects were not preyed upon to extinction without fire to identify & deter predators. Hadza hunter-gatherers comfortably sleep through the night, typically by taking turns “on watch” while the others rest.

The Archaeological Record

We are positing that erects learned to create and controlling fire 2 mya. Is that a feasible hypothesis?

Habilines had learned how to create stone tools 2.6 million years ago. By the time of the erects, techniques to create these tools had persisted for 600,000 years. So it is safe to say that our ancestors were able to retain useful cultural innovations.

Independent environmental reasons link fire-making with H Erectus. The Atlas mountain range is the most likely birthplace of this species, and this dry area fires triggered by lightning are an annual hazard. Hominins living in such environments would be more intimately familiar with fire than those with less combustible vegetation zones.

Erects would have seen sparks when they hit stones together to make tools. But the sparks produced by many kinds of rock are too cool to catch fire. However, when pyrites (a fairly common ore) are hit against flint, the results are used by hunter-gatherers to reliably produce fire. The Atlas mountain range is renowned for being exceptionally rich in minerals:

Why is Morocco one of the world’s great countries for minerals? No glaciers! Many of the world’s most colorful minerals are found in deposits at the surface, formed over time by the interaction of water, air and rock. Glaciers remove all of that good stuff (as happened in Canada recently, geologically speaking) – and with no recent glaciation, Morocco hosts many fantastic occurrences of minerals unlike any in parts of the world stripped bare during the last Ice Age.

Since this mountain range contains pyrites, early erects could have found themselves inadvertently making fire rather often.

Once it is created, fire is relatively easy to keep going. And it does not take much creativity to stick food a fire. Moreover, modern-day chimps prefer cooked food over raw; it is hard to imagine H Erectus finding cooked food distasteful. All of these considerations suggest an early control of fire is at least plausible.

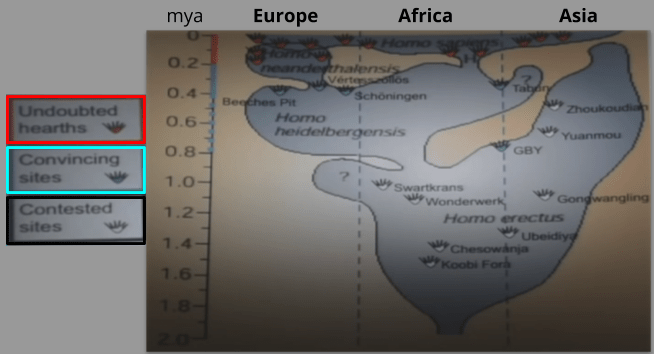

We can consult the archaeological record to see record of man-made fire (i.e., hearths). This is bad news for the cooking hypothesis! There is strong evidence for hearths dating back to 800 mya and the advent of archaic humans. Before then, there are six sites that seem to be hearths; but these are not universally acknowledged as such.

But absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence, right?

No! That idiom is wrong. Silence is evidence of absence. It’s just that the strength of the evidence depends on the nature of the hypothesized entity.

- If you think an unidentified planet orbits the Sun, a lack of evidence would weigh heavily against the hypothesis.

- If you think an unidentified pebble orbits the Sun, a lack of evidence doesn’t say much one way of the other.

Wrangham argues that evidence of hearths are more fragile than e.g. fossils, and points to facts like there are zero hearths recorded for modern humans during European “ice ages” – but we know these must have existed. It is possible that the contested hearth sites will ultimately be vindicated, and that we just can’t see much evidence.

Despite these claims about evidential likelihood, the silence of the archaeological record is undeniably a significant objection to the theory.

Weighing The Evidence

Is the cooking hypothesis true? Let us weigh the evidence, and contrast it with alternative hypotheses.

The most plausible alternative hypothesis is that archaic humans H. Heidelbergensis discovered cooking. But the emergence of that species involved an increase in brain size, and more sophisticated culture & hunting technology. Neither adaptation seems strongly connected to cooking. In contrast, the H. Erectus adaptations would have all been strongly affected by cooking.

Moreover, alternative hypotheses must still answer the five paradoxes of hominization:

- Digestive Apparati. Why did erects evolve smaller mouths, weaker jaws, smaller teeth, small stomachs, and shorter colons?

- Expensive Tissue. How did the erects find the calories to finance more brain tissue?

- Time Budget. How could erects afford spending 3-8 hours per day engaged in the risky strategy hunting?

- Thermal Vulnerability. Erects also managed to migrate to non-African climates such as Europe. How did these creatures stay warm?

- Predator Safety. Erects slept on the ground. How did they avoid predation?

The habilines ate meat. It is unclear how they did so (hunting or scavenging), but we have strong evidence that they did. Meat is a much higher quality food than tubers (cf. paranthropes) or fruit (cf. chimpanzees). The meat-eating hypothesis argues that meat eating was the primary driver of hominization.

Meat-eating resolves the Expensive Tissue paradox (meat allows for brain growth) and Digestive Apparati (carnivores are known to have smaller guts). But it doesn’t address why a meat-eater would develop smaller canines. And it struggles to explain how the reduction in gut size is compatible with the tuber component of the erect diet. And what about time budget, thermal vulnerability, and predator safety? The meat eating hypothesis fails to address these paradoxes entirely.

Which is more likely to occur in the next twenty years: undisputed evidence for early control of fire, or an alternate theory that resolves all five hominization paradoxes?

My money is on the former.

References

- Wrangham (). Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human

- Aiello & Wheeler(1995). The expensive tissue hypothesis: the brain and the digestive system in primate and human evolution.