Core Sequence

Semantic Memory

Other

Core Sequence

Semantic Memory

Other

Part Of: Neural Architecture sequence

Content Summary: 700 words, 7 min read

Dual-Process Theory

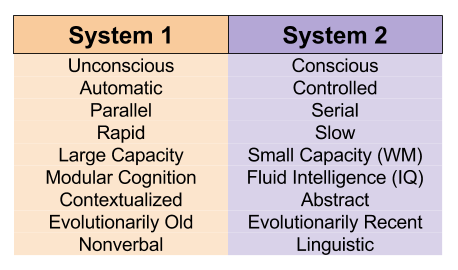

Dual process theory identifies two modes of human cognition: a fast, parallel System 2 and a slow, serial System 1.

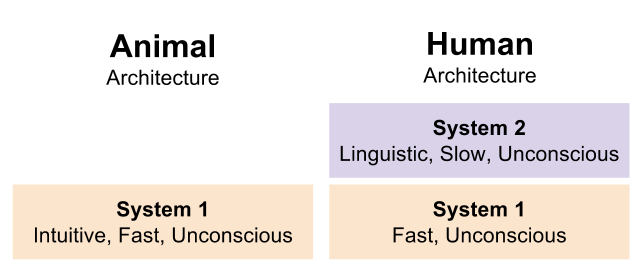

This distinction can be expressed phylogenetically:

But this is incorrect. We know that engine of consciousness is the extended reticular-thalamic activating system (ERTAS), which implements feature integration by phase binding. Mammalian brains contain this device. Also, behavioral evidence indicate that non-human animals possess working memory and fluid intelligence[C13].

Conscious, non-linguistic animals exist. We need a phylogeny that accepts this fact.

The Tripartite Mind

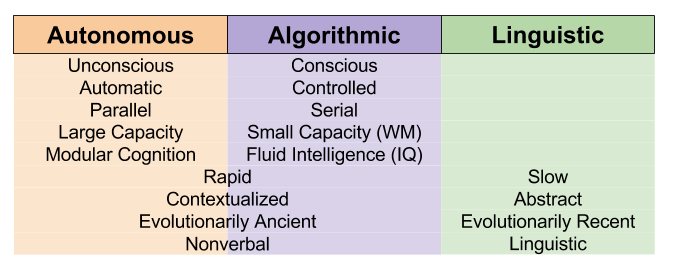

Let’s rename System 1, and divide System 2 into two components.

This allows us to conceive of conscious, non-verbal mammals:

This lets us refresh our view of property dissociations:

Most dual-process theorizing (for example, our theory of moral cognition) maps neatly to the autonomous and linguistic mind, respectively.

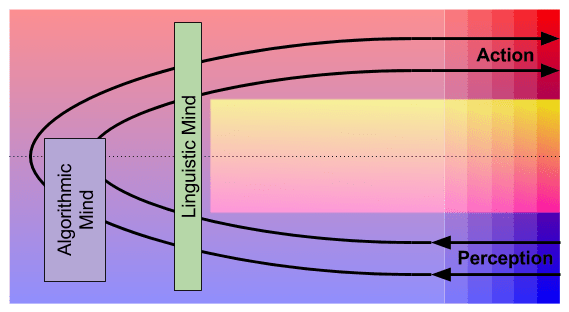

But the Tripartite Mind theory cannot bear the weight of all behavioral phenomena. For that, we need the more robust language of two loops. In fact, we can marry these two theories as follows:

This diagram reflects the following facts:

Boundaries on the Linguistic Mind

The Linguistic Mind creates cultural knowledge. It is the technology underlying the invention of agriculture, calculus, and computational neuroscience. It is hard to see how such a device could be not only biased, but in some respects completely blind.

But the Linguistic Mind does not have access to raw sensorimotor signals. It only has access to the intricately curated working memory. You cannot communicate mental experiences outside of working memory. You can try, but that would be confabulation (unintentional dishonesty). As [NW77] describe in their seminal paper Telling more than we can know, in practice, human beings are strangers to themselves.

The evidence suggests that working memory does not contain any information about your judgments and decision making. All attempts to describe this aspect of our inner life fail. Introspection on these matters cannot secure direct access to the truth of the matter. Rather, we guess at our own motives, using the exact same machinery we use to interpret the behavior of other people. For more on the Interpretive Sensory Access theory of introspection [C10], I recommend this lecture.

Sociality and the Linguistic Mind

Per the Social Brain Hypothesis [D09], humans are not more intelligent than other primates; we are rather more social. In other words, the Linguistic Mind is a social invention, which facilitates the construction of cultural institutions which allow propriety frames to be synchronized more explicitly.

On the argumentative theory of reasoning, social reasoning is not independent of language. It is the purpose of language.

While the Linguistic Mind evolved to satisfy social selection pressures, not all primate sociality is linked to this device. Social mechanisms have arrived in stages:

All of these mechanisms can be attributed to the Autonomous Mind. But since the Linguistic Mind is driven by our motivation apparatus (just like everything else in the brain), its behavior is sensitive to the wishes of these “lower” modules. This doesn’t contradict our earlier assumption that its content is divorced from Autonomous data.

References

Information Theory

Linguistics

Evolution of Language

Sociolinguistics

Part Of: Machine Learning sequence

Content Summary: 800 words, 8 min read

Projection as Geometric Approximation

If we have a vector and a line determined by vector

, how do we find the point on the line that is closest to

?

The closest point is at the intersection formed by a line through

that is orthogonal to

. If we think of

as an approximation to

, then the length of

is the error of that approximation.

This formula captures projection onto a vector. But what if you want to project to a higher dimensional surface?

Imagine a plane, whose basis vectors are and

. This plane can be described with a matrix, by mapping the basis vectors onto its column space:

Suppose we want to project vector onto this plane. We can use the same orthogonality principle as before:

Matrices like are self-transpositions. We have shown that such matrices are square symmetric, and thereby contain positive, real eigenvalues.

We shall assume that the columns of are independent, and it thereby is invertible. The inverse thereby allows us to solve for

:

Recall that,

Since matrices are linear transformations (functions that operate on vectors), it is natural to express the problem in terms of a projection matrix , that accepts a vector

, and outputs the approximating vector

:

By combining these two formula, we solve for :

Thus, we have two perspectives on the same underlying formula:

Linear Regression via Projection

We have previously noted that machine learning attempts to approximate the shape of the data. Prediction functions include classification (discrete output) and regression (continuous output).

Consider an example with three data points. Can we predict the price of the next item, given its size?

For these data, a linear regression function will take the following form:

We can thus interpret linear regression as an attempt to solve :

In this example, we have more data than parameters (3 vs 2). In real-world problems, it is an extremely common predicament. It yields matrices with may more equations than unknowns. This means that has no solution (unless all data happen to fall on a straight line).

If exact solutions are impossible, we can still hope for an approximating solution. Perhaps we can find a vector p that best approximates b. More formally, we desire some such that the error

is minimized.

Since projection is a form of approximation, we can use a projection matrix to construct our linear prediction function .

A Worked Example

The solution is to make the error as small as possible. Since

can never leave the column space, choose the closest point to

in that subspace. This point is the projection

. Then the error vector

has minimal length.

To repeat, the best combination is the projection of b onto the column space. The error is perpendicular to that subspace. Therefore

is in the left nullspace:

We can use Guass-Jordan Elimination to compute the inversion:

A useful intermediate quantity is as follows:

We are now able to compute the parameters of our model, :

These parameters generate a predictive function with the following structure:

These values correspond with the line that best fits our original data!

Wrapping Up

Takeaways:

Related Resources:

Part Of: Demystifying Language sequence

Content Summary: 1200 words, 12 min read.

The Structure of Reason

Learning is the construction of beliefs from experience. Conversely, inference predicts experience given those beliefs.

Reasoning refers to the linguistic production and evaluation of an argument. Learning and inference are ubiquitous across all animal species. But only one species are capable of reasoning: human beings.

Argument can be understood by the lens of deductive logic. Logical syllogisms are a calculus that maps premises to conclusions. An argument is valid if the conclusions follow from the premises. An argument is sound if it is valid, and its premises are true.

Premises can be evaluated directly via intuition. The relationship between argument structure and intuition parallels decision trees versus evaluative functions.

Two Theories of Reason

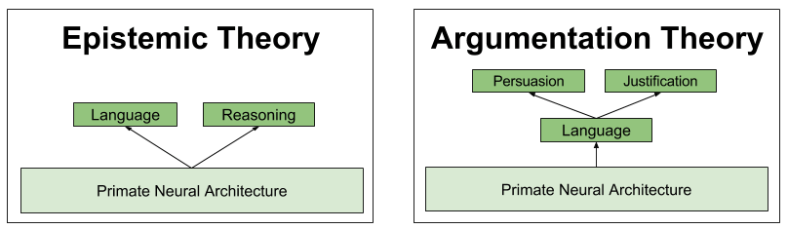

Why did reasoning evolve? What is its biological purpose? Consider the following theories:

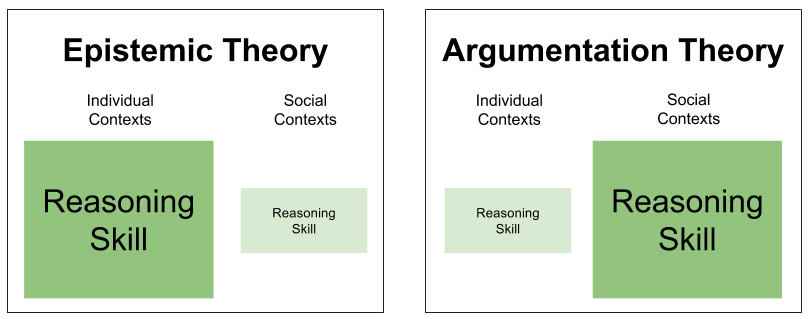

One way to adjudicate these rival theories is to examine domain gradients. Roughly, a biological mechanism performs optimally when situated in contexts for which they were originally designed. Our cravings for sugars and fats mislead us today, but encourage optimal foraging in the Pleistocene epoch.

Reasoning is used in both individual and social contexts. But our theories disagree on which is the original domain. Thus, they generate opponent predictions as to which context will elicit the most robust performance.

Here we see our first direct confirmation of the argumentative theory: in practice, people are terrible at reasoning in individual contexts. Their reasoning skills become vibrant only when placed in social contexts. It’s a bit like Kevin Malone doing mental math. 🙂

Structure of Argumentative Reason

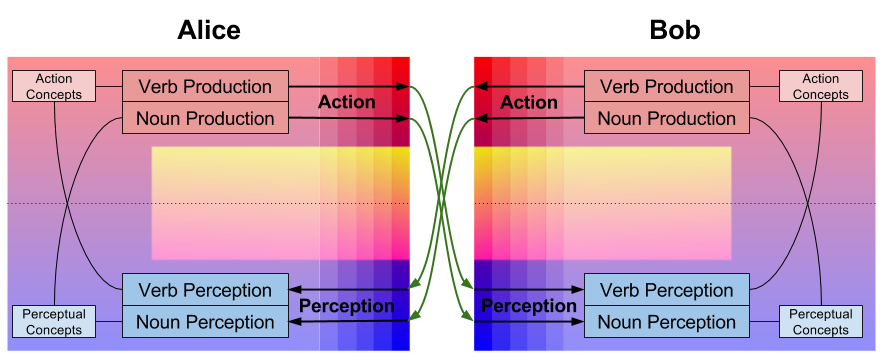

All languages ever discovered contain both nouns and verbs. This universal distinction reflects the brain’s perception-action dichotomy. Nouns express perceptual concepts, and verbs express action concepts.

Recall that natural language has two processes: speech production & speech comprehension. These functions both accept nouns and verbs as arguments. Thus, we can express the cybernetics of language as follows:

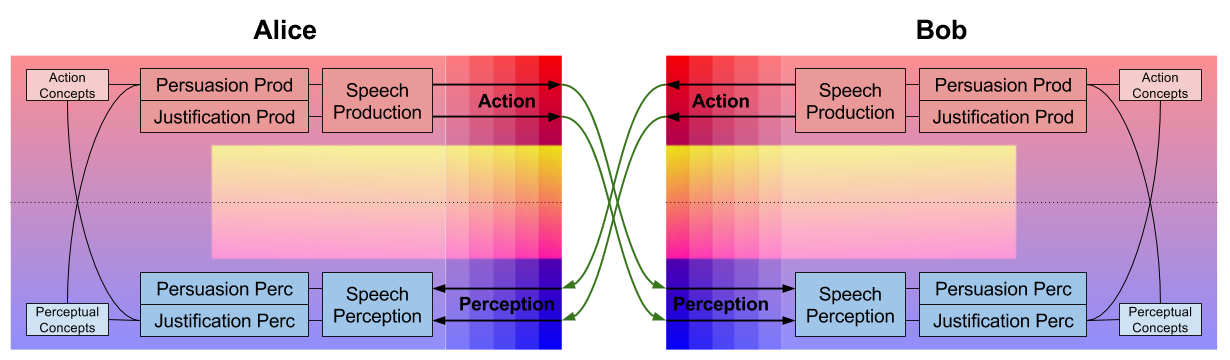

Argumentative reasoning is a social extension of the faculty of language. It consists of two processes:

Persuasion and justification draw on perceptual and action concepts, respectively. Thus, the persuasion-justification distinction mirrors the noun-verb distinction, but at a higher level of abstraction. Here is our cybernetics of reasoning diagram.

We return to phylogeny. Why did reasoning-as-argumentation evolve?

For communication to persist, it must benefit both senders and receivers. But stability is often threatened by senders who seek to manipulate receivers. We know that humans are gullible by default. Nevertheless, our species does possess lie detection devices.

The evolution of argumentative reason was shaped by a similar set of ecological pressures as that of language. Let me cover these hypotheses in another post.

For now, it helps to think of belief as clothes, serving both pragmatic and social functions. A wide swathe of biases stems from persuasive arguments performing social rather than epistemic ends. This is not to say that truth is irrelevant to reasoning. It is simply not always the dominant factor.

On Persuasion

Persuasion processes involve arguments about beliefs. It has two subprocesses: argument production (listener persuasion) and argument evaluation (argument quality inspection). These two processes are locked in an evolutionary arms race, developing ever more sophisticated mechanisms to defeat the other.

Argument production is responsible for the two most damning biases in the human repertoire. There is extensive evidence that we are subject to confirmation bias: the attentional habit to preferentially examine evidence that helps our case. We are also victim to motivated reasoning, which biases our judgments towards our self-interest. We often describe instances of motivated reasoning as hypocrisy.

Consider the following example:

There are two tasks one short & pleasant, the other long & unpleasant. Selectors are asked to select their task, knowing that the other task is giving to another participant (the Receiver). Once they are done with the task, each participant states how fair the Selector has been. It is then possible to compare the fairness ratings of Selectors versus those of the Receivers.

Selectors rate their decisions as more fair than the Receivers, on the average. However, if participants are distracted when they asked their fairness judgments, the ratings were identical and showed no hint of hypocrisy. If reasoning were not the cause of motivated reasoning but the cure for it, the opposite would be expected.

In contrast to production, argument evaluation involves two subprocesses: trust calibration and coherence checking. The ability to distrust malevolent informants has been shown to develop in stages between the ages of 3 and 6.

Coherence checking is less self-serving than production mechanism. In fact, it is responsible for the phenomenon of truth wins. For example, in group puzzles the person whoever stumbles on the solution will successfully persuade her peers, regardless of her social standing. In practice, good arguments tend to be more persuasive than bad arguments.

On Justification

Justification processes involve reasons about behavior. This is not to be confused with motivations for behavior, which happen at the subconscious level. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that the reasons we acquire by introspection are not true. It has been consistently observed that attitudes based on reasons are much less predictive of future behaviors (and often not predictive at all) than were attitudes stated without recourse to reasons.

The justification module produces reason-based choice; that is, we tend to choose behaviors that are easy to justify to our peers. Reason-based choice explains an impressive number of documented human biases. For example,

The sunk cost fallacy is the tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment has been made. It doesn’t occur in children or non-human animals. If reasoning were not the cause of this phenomenon but the cure for it, the opposite would be expected.

The disjunction effect, endowment effect, and decoy effect can similarly be explained in terms of reason-based choice.

This is not to say that justification is insensitive to the truth. Better decisions are usually easier to justify. But when a more easily justifiable decision is not a good one, reasoning still drives us towards ease of justification.

Theory Evaluation

I was initially skeptical of the argumentative theory because it felt “fashionable” in precisely the wrong sense, underwritten by postmodern connotations of narrative-is-everything and epistemic nihilism. Another warning flag is that the theory draws from the field of social psychology, which has been quite vulnerable to the replication crisis.

However, the evidential weight in favor of the argumentative theory has recently persuaded me. For a comphrehensive view of that evidence, see [MS11]. I no longer believe argumentative reason entails epistemic nihilism, and I predict its evidential basis will not erode substantially in coming decades.

I am also attracted to the theory because it helps tie together several other theories into a comprehensive meta-theory: The Tripartite Mind. Let me sketch just one of example of this appeal.

The heuristics and biases literature has uncovered a bewildering variety of errors, shortcuts, and idiosyncrasies in human cognition. Responses to this literature vary widely. But too many voices take such biases as “conceptual atoms”, or fundamental facts of the human brain. Neuroscience can and must identify the mechanisms underlying these phenomena.

The argumentative theory is attractive in that it explains a wide swathe of the zoo.

Takeaway

Reason is not a profoundly flawed general mechanism. Instead, it is an efficient linguistic device adapted to a certain type of social interaction.

References

[MS11]. Mercer & Sperber (2011). Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory.

Part Of: Machine Learning sequence

Content Summary: 500 words, 5 min read

Motivations

Data scientists are in the business of answering questions with data. To do this, data is fed into prediction functions, which learn from the data, and use this knowledge to produce inferences.

Today we take an intuitive, non-mathematical look at two genres of prediction machine: regression and classification. Whereas these approaches may seem unrelated, we shall discover a deep symmetry lurking below the surface.

Introducing Regression

Consider a supermarket that has made five purchases of sugar from its supplier in the past. We therefore have access to five data points:

One of our competitors intends to buy 40kg of sugar. Can we predict the price they will pay?

This question can be interpreted visually as follows:

But there is another, more systematic way to interpret this request. We can differentiate training data (the five observations where we know the answer) versus test data (where we are given a subset of the relevant information, and asked to generate the rest):

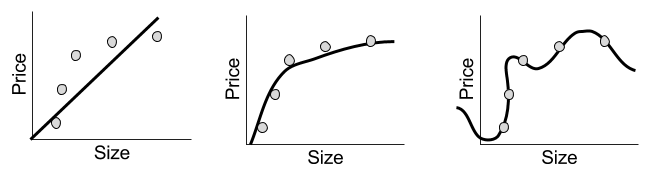

A regression prediction machine will for any hypothetical x-value, predicts the corresponding y-value. Sound familiar? This is just a function. There are in fact many possible regression functions, of varying complexity:

Despite their simple appearance, each line represents a complete prediction machine. Each one can, for any order size, generate a corresponding prediction of the price of sugar.

Introducing Classification

To illustrate classification, consider another example.

Suppose we are an animal shelter, responsible for rescuing stray dogs and cats. We have saved two hundred animals; for each, we record their height, weight, and species:

Suppose we are left a note that reads as follows:

I will be dropping off a stray tomorrow that is 19 lbs and about a foot tall.

A classification question might be: is this animal more likely to be a dog or a cat?

Visually, we can interpret the challenge as follows:

As before, we can understand this prediction problem as taking information gained from training data, to generate “missing” factors” from test data:

To actually build a classification machine, we must specify a region-color map, such as the following:

Indeed, the above solution is complete: we can produce a color (species) label for any new observation, based on whether it lies above or below our line.

But other solutions exist. Consider, for example, a rather different kind of map:

We could use either map to generate predictions. Which one is better? We will explore such questions next time.

Comparing Prediction Methods

Let’s compare our classification and regression models. In what sense are they the same?

If you’re like me, it is hard to identify similarities. But insight is obtained when you compare the underlying schemas:

Here we see that our regression example was 2D, but our classification example was 3D. It would be easier to compare these models if we removed a dimension from the classification example.

With this simplification, we can directly compare regression and classification:

Thus, the only real difference between regression and classification is whether the prediction (the dependent variable) is continuous or discrete.

Until next time.

Main Sequence

Central Principles sequence

Optimization Techniques sequence

Sociology of ML

Related sequences

Part Of: Demystifying Ethics sequence

Followup To: An Introduction To Ethical Theories

See Also: Shelly Kagan (1994). The Structure of Normative Ethics

Content Summary: 700 words, 7 min read

Are Ethical Theories Incompatible?

Last time, we introduced five major ethical theories:

At first glance, we might consider these theories as rivals competing for the status of a ground for morality. However, when discussing these theories, one has a distinct sense that they are simple addressing different concerns.

Perhaps these theories are compatible with one another. But it is hard to see how, because we lack a map of the major conceptual regions of normative ethics, and how they relate to one another.

Let’s try to construct such a map.

Identifying Morally Relevant Factors

There are two major activities in the philosophical discourse about normative ethics: factorial analysis, and foundational theories.

Factorial analysis involves getting clear on which variables affect in our moral judgments. This is the goal of moral thought experiments. By constructing maps from situations to moral judgment, we seek to understand situational factors that contribute to (and compete for control over) our final moral appraisals.

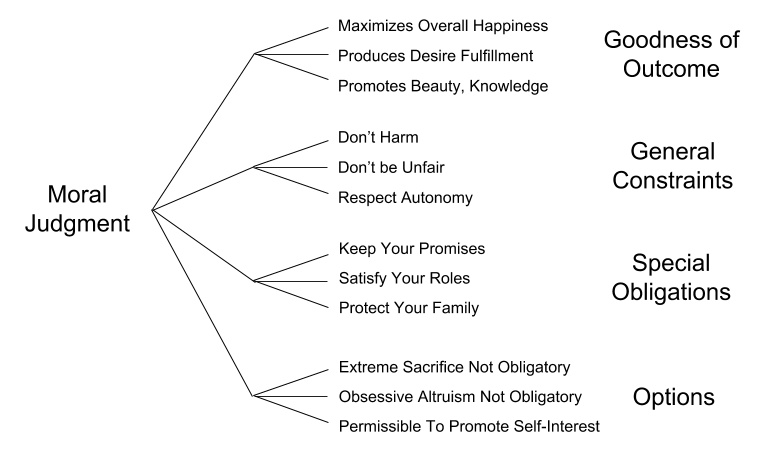

We can discern four categories of factors which bear on moral judgments: Goodness of Outcome, General Constraints, Special Obligations, and Options. We might call these categories factorial genres. Here are some example factors from each genre.

While conducting factorial analysis, we typically ask questions about:

Constructing Foundational Theories

A foundational mechanism is a conceptual apparatus designed to generate the right set of morally relevant factors. An example of such a theory is contractarianism, which roughly states that:

Morally relevant factors are those which would be agreed to by a social community, if they were placed in an Original Position (imagine you are designing a social community from scratch), and subject to the Veil of Ignorance (you don’t know the details of what your particular role will be).

Thus, our two philosophic activities relate as follows:

These two activities are fueled by different sets of intuitions.

Let us examine other accounts of foundational mechanisms. These claim that we should accept only morally relevant factors that…

Localizing Ethical Theories in our Map

We can now use this scheme to better understand the space of ethical theories.

Proposition 1. Ethical theories can be decomposed into their foundational and factorial components.

Three of our five ethical theories have the following decomposition:

Proposition 2. Factorial pluralism is compatible with foundational monism.

Certain flavors of consequentialists, deontologists, consequentialists insist on factorial monism, that only one kind of moral factor really matters.

But as a descriptive matter, it seems that human morality is sensitive to many different kinds of factors. Outcome valence, action constraint, role-based obligations all seem to play in real moral decisions.

Factorial monism has the unpleasant implication of demonstrating some of these factors as misguided. But philosophers are perfectly free to affirm factorial pluralism: that each intuition “genre” are prescriptively justified.

Some examples of one foundational device generating a plurality of genres:

Takeaways

Are ethical theories truly competitors? One might suspect that the answer is no. Ethical theories seem to address different concerns.

We can give flesh to this intuition by analyzing the structure of ethical theories. They can be decomposed into two parts: factorial analysis, and foundational mechanisms.

Most defenses of foundational mechanisms have them generating a single factorial genre. However, it is possible to endorse factorial pluralism. There is nothing incoherent in the view that e.g., both event outcome and general constraints bear on morality.

This taxonomy allows us to contrast ethical theories in a new way. Utilitarianism can be seen as a theory about the normative factors, contractarianism is a foundational mechanism. Far from being rival views, one could in fact endorse both!

Content Summary: 1400 words, 7 min read.

Original Author: Scott Alexander

Recently on both sides of the health care debate I have been hearing people make a very dangerous error. They point to a situation in which someone was denied coverage for a certain treatment because it was expensive and unproven, and say: “This is an outrage! We can’t let ‘death panels’ say some lives aren’t worth saving! How can people say money is more important than a human life? We have a moral duty to pay for any treatment, no matter how expensive, no matter how hopeless the case, if there is even the tiniest chance that it help this poor person.”

All of these are simple errors. Contrary to popular belief, you can put a dollar value on human life. That dollar value is $5.8 million. Denying this leads to terrible consequences.

Let me explain.

On The Risks of Dying

Consider the following:

A man has a machine with a button on it. If you press the button, there is a one in five million chance that you will die immediately; otherwise, nothing happens. He offers you some money to press the button once. What do you do? Do you refuse to press it for any amount? If not, how much money would convince you to press the button?

What do you think?

If you answered something like “Never for any amount of money,” or “Only for a million dollars”, you’re not thinking clearly.

One in five million is pretty much your chance of dying from a car accident every five minutes that you’re driving. Choosing to drive for five minutes is exactly equivalent to choosing to press the man’s button. If you said you wouldn’t press the button for fifty thousand dollars, then in theory if someone living five minutes away offers to give you fifty thousand dollars no strings attached, you should refuse the offer because you’re too afraid to drive to their house.

Likewise, if you drive five minutes to a store to buy a product, instead of ordering the same product on the Internet for the same price plus $5 shipping and handling, then you should be willing to press the man’s button for $5.

When I asked this question to several friends, about two-thirds of them said they’d never press the button. This tells me people are fundamentally confused when they consider the value of life. When asked directly how much value they place on life, they always say it’s infinite. But people’s actions show that in reality they place a limited value on their life; enough that they’re willing to accept a small but real chance of death to save five bucks. And as we will see, that is a very, very good thing.

Insurance Example: Fixed Costs

Consider the following:

Imagine an insurance company with one hundred customers, each of whom pays $1. This insurance company wants 10% profit, so it has $90 to spend. Seven people on the company’s plan are sick, with seven different diseases, each of which is fatal. Each disease has a cure. The cures cost, in order, $90, $50, $40, $20, $15, $10, and $5.

We have decided to give everyone every possible treatment. So when the first person, the one with the $90 disease, comes to us, we gladly spend $90 on their treatment; it would be inhuman to just turn them away. Now we have no money left for anyone else. Six out of seven people die.

The fault here isn’t with the insurance company wanting to make a profit. Even if the insurance company gave up its ten percent profit, it would only have $10 more; enough to save the person with the $10 disease, but five out of seven would still die.

A better tactic would be to turn down the person with the $90 disease. Instead, treat the people with $5, $10, $15, $20, and $40 diseases. You still use only $90, but only two out of seven die. By refusing treatment to the $90 case, you save four lives. This solution can be described as more cost-effective; by spending the same amount of money, you save more people. Even though “cost-effectiveness” is derided in the media as being opposed to the goal of saving lives, it’s actually all about saving lives.

If you don’t know how many people will get sick next year with what diseases, but you assume it will be pretty close to the amount of people who get sick this year, you might make a rule for next year: Treat everyone with diseases that cost $40 or less, but refuse treatment to anyone with diseases that cost $50 or more.

Insurance Example: Probabilistic Costs

There is a similar argument applies to medical decisions that involve risk. Consider:

You have $900. There are four different fatal diseases: A, B, C, and D. There are 40 patients, ten with each disease. with four different fatal diseases. Each disease costs $300 to cure.

In this case, your only option is to cure A, B, and C… and tell patients with D that unfortunately there’s not enough left over for them.

But what if the cure for A only had a 10% chance of working? In this case, you cure A, B, and C and have, on average, 21 people left alive.

Or you could tell A that you can’t approve the treatment because it’s not proven to work. Now you use your $90 to treat B, C, and D instead, and you have on average 30 people left alive. By denying someone an unproven treatment, you’ve saved 9 lives.

Computing the Value of a Life

So, in the real world, how should we decide how much money is a good amount to spend on someone?

I mentioned before that people don’t act as if the lives of themselves or others are infinitely valuable. They act as if they have a well-defined price tag. Well, some enterprising economists have figured out exactly what that price tag is. They made their calculations by examining, for example, how much extra you have to pay someone to take a dangerous job, or how much people who are spending their own money are willing to spend on unproven hopeless treatments. They determined that most people act as if their lives were worth, on average, 5.8 million dollars.

Most health care, government or private, uses a similar calculation. One common practice is to value an extra year of healthy life at $50,000. So:

I’m not claiming I have any of the answers to this health care thing. I’m not claiming that $50,000 is or isn’t a good number to value a year of life at. I’m not saying that government health care couldn’t become much more efficient and save lots of money, or that private health care couldn’t come up with a better incentive system that makes denying treatments less common and less traumatizing. I’m not saying that insurance companies don’t make huge and stupid mistakes when performing this type of analysis, or even that they aren’t the slime of the earth. I’m not saying the insurance system is currently fair to the poor, whatever that means. I’m not saying that there aren’t many many variables not considered in this simplistic analysis, or anything of that sort.

I am saying that if you demand that you “not be treated as a number” or that your insurance “never deny anyone treatment as long as there’s some chance it could help”, or that health care be “taken out of the hands of bureaucrats and economists”, then you will reap what you have sown: worse care and a greater chance of dying of disease, plus the certainty that you have inflicted the same on many others.

I’m also saying that this is a good example of why poorly informed people who immediately get indignant at anything packaged by the media as being “outrageous”, even when their “hearts are in the right places”, end up poisoning a complicated issue and making it harder for responsible people to make any progress.